Aan dit artikel is vele uren gewerkt en mocht u kanker-actueel de moeite waard vinden en ons willen ondersteunen om kanker-actueel online te houden dan kunt u ons machtigen voor een periodieke donatie via donaties: https://kanker-actueel.nl/NL/donaties.html of doneer al of niet anoniem op - rekeningnummer NL79 RABO 0372931138 t.n.v. Stichting Gezondheid Actueel in Amersfoort. Onze IBANcode is NL79 RABO 0372 9311 38

Elk bedrag is welkom. En we zijn een ANBI instelling dus uw donatie of gift is in principe aftrekbaar voor de belasting.

14 janauri 2017: Bron: Verschillende studies uit Pubmed

Monoterpene Perillyl Alcohol geeft uitstekende resultaten bij hersentumoren en ook bij uitzaaiingen in de hersenen vanuit andere vormen van kanker. Maar vooral was het effect opvallend groot bij hersentumoren (glioma's) van het type astrocytomen en een recidief van een glioblastoma werd de progressievrije ziektetijd sterk vergroot, Bij de laatste groep bereikte Perillyl alcohol een nagenoeg verdubbeling van de progressievrije tijd in vergelijking met resultaten uit eerdere studies als controlegroepen gehaald uit bestaande literatuur.

Uit een laatste studie bleek dat 19% van de patienten met een recidief van een Glioma Blastoma op basis van alleen POH - Monoterpene Perillyl Alcohol nog steeds na 4 jaar in leven zijn.

Dit is de conclusie uit een recent studierapport (december 2016) in het Engels maar verderop in dit artikel beschrijf en vertaal ik de belangrijkste gegevens in het Nederlands enz.

In conclusion,

- (a) long-term POH inhalation was a safe and noninvasive therapeutic strategy for malignant gliomas;

- (b) long-term POH inhalation consistently improved survival of patients with grade III and grade IV AA with oligodendroglia component;

- c) patients with secondary GBM had a better response to POH inhalation than patients with primary GBM; (d) 19% of recurrent malignant glioma patients still remain in clinical remission after 4 years under exclusive POH inhalation treatment;

- (e) long-term POH inhalation did not cause any evident clinical and /or laboratory-based toxicity.

- We can envisage in a near future the synthesis of biologically-active hybrid molecules containing POH as a carrier conjugated to drugs specifically targeting critical regulators of cell proliferation, as a promising antitumor therapeutic strategy successfully employed to treat brain tumors.

Bv. uit een studie met 89 patiënten met een recidief van een hersentumor van het type glioblastoma die werden behandeld met een neusspray van POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) werd vergeleken met een controlegroep van 52 patiënten met primaire Glioblastoma maar die geen behandeling meer hadden gekregen maar alleen ondersteunende palliatieve hulp omdat de kanker al te ver was doorgedrongen.

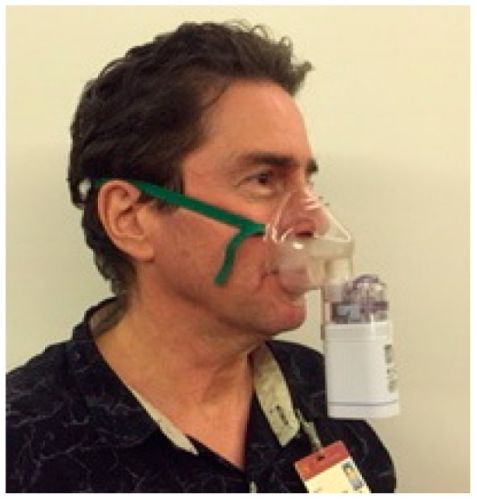

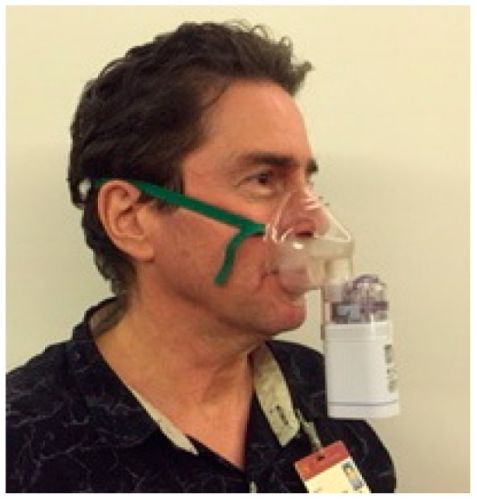

Foto laat een man zien die via een neusspray de POH binnen krijgt. Tekst gaat onder foto verder

De patiënten met een recidief van een primaire Glioblastoma die alleen daarna met POH werden behandeld leefden met de neusspray met POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) mediaan gemeten 11.2 maanden, langer (log rank test, P = 0.0366) dan de patienten uit de Glioblastomagroep met een primaire status die mediaan 5.9 maanden leefden na de start van de studie. Opvallend was dat POH het beste werkte bij patiënten met een dieper in de hersenstam doorgedrongen tumorcellen dan die waarbij de tumor nog minder ver was doorgedrongen in de hersenen. Vermindering van corticosteroiden (36%) blijkt gerelateerd aan langzamere progressie van de ziekte.

De bijwerkingen van POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) als neusspray toegediend zijn nagenoeg nihil. 1 patiënt uit deze studie overleeft al 5 jaar haar hersentumor met alleen POH als medicijn. Zie haar studierapport als case studie gepubliceerd:

Case of Advanced Recurrent Glioblastoma Successfully Treated with Monoterpene Perillyl Alcohol by Intranasal Administration

Intranasale POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) bevordert duurzame overall overleving van een recidief van een Glioma Blastoma

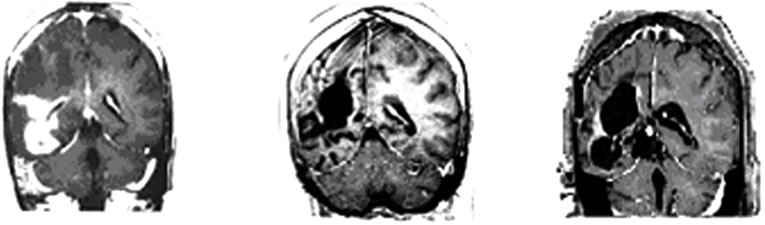

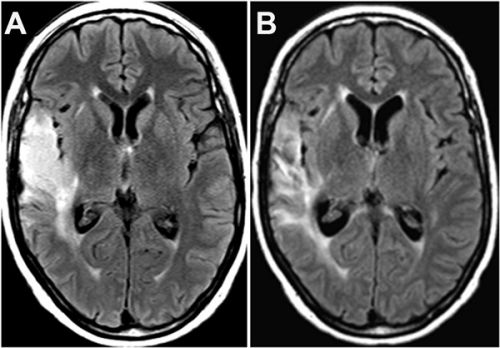

Hieronder beelden van deze vrouw haar scans. In het studierapport staan er meer.

Tekst gaat onder beeld verder.

Brain MRI done in October 2009 still revealed irregular

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. MRI brain image of recurrent GBM before and after POH intranasal administration. Note the decrease in tumor size between the initial MRI ((a); (d)) at the time of inclusion in POH protocol, images obtained in August 2008 ((b); (e)) and performed after 4 years and 9 months ((c) and (f)) of daily treatment with POH by intranasal route.

In een andere Fase I/II studie werd POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) via een neusspray toegediend bij patiënten met een recidief van een kwaadaardige glioma nadat zij vooraf waren behandeld met operatie, radiotherapie - bestraling en chemotherapie (Temozomide - Temodal). De POH werd toegediend in een concentratie van 0.3% volume/volume (55 mg) 4 keer per dag in een onderbroken schema.

De studiegroep bestond uit 37 patiënten, 29 patiënten met een glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), 5 met een astrocytoom graad III (AA), en 3 met een anaplastisch oligodendroglioma (AO).

Het objectieve doel van deze studie was de toxiciteit en de progressievrije tijd (PFS) te meten 6 maanden na de start van de behandeling. Neurologisch onderzoek en CT scans en MRI-scans zouden ziekteprogressie moeten vaststellen en bevestigen. Een CR = Complete remissie (response) werd gedefinieerd als neurologisch stabiel of verbetering van de conditie, geen zichtbare actieve tumoren meer op een CT/MRI scan en het niet meer nodig hebben van corticosteroiden (o.a. dexamethason is een van de meest gebruikte corticostiroiden);

Een PR = partiële remissie - response werd gedefinieerd als gelijk of meer dan 50% vermindering van tumoromvang op een CT/MRI scan, neurologische stabiliteit of verbetering van de conditie en geen gebruik meer van corticosteroiden;

PC = Progressieve ziekte (PC) werd gedefinieerd als gelijk of minder dan 25% vermindering van tumorvolume op een CT/MRI scan en het verschijnen van nieuwe tumoren.

SD = Stabiele ziekte werd gedefinieerd als er geen sprake was van verandering in progressie van de ziekte, noch in tumoromvang op een CT/MRI scan noch in neurologische status.

De resultaten uit deze studie:

Na 6 maanden behandeling zoals in de doelen geformuleerd:

Een PR - partiële remissie werd gezien bij 3.4% (n=1) van de patienten met een Glioblastoma en 33.3% (n=1) bij patiënten met een anaplastisch oligodendroglioma (AO);

SD - stabiele ziekte 44.8% (n=13) bij patienten met een Glioblastoma (GBM), 60% (n=3) bij patiënten met een Astrocytoom (AA), en 33.3% (n=1) bij patiënten met een anaplastisch oligodendroglioma (AO);

PC - progressieve ziekte werd vastgesteld bij 51.7% (n=15) van de patiënten met een Glioblastoom (GBM), 40% (n=2), bij patiënten met een Astrocytoom (AA) en 33.3% (n=1) bij patiënten met een anaplastisch oligodendroglioma (AO).

PFS = Progressievrije ziekte of SD = Stabiele ziekte werd gezien bij 48.2% (n = 14) van de patiënten met een Glioblastoma (GBM), 60% (n = 3) bij patiënten met een Astrocytoom (AA), en 66.6% (n = 2) bij patiënten met een anaplastisch oligodendroglioma (AO).

Conclusie:

De onderzoekers van deze studie concluderen hetzelfde als de onderzoekers uit de eerdere studie namelijk: deze resultaten suggereren dat intra nasale toediening van POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) een veilige en niet invasieve goedkope behandeling is. Er waren geen meldingen van toxiciteit en de regressie van de tumoren bij sommige patiënten suggereert dat POH ook een anti tumor effectiviteit heeft.

In een andere case studie wordt het verloop van de ziekte bij een patiënt - een blanke vrouw van 51 jaar - met een recidief van een Glioblastoma beschreven. Deze patient gebruikte POH naast voortdurende temozomide (Temodal): Perillyl alcohol inhalation concomitant with oral temozolomide halts progression of recurrent inoperable glioblastoma: a case report

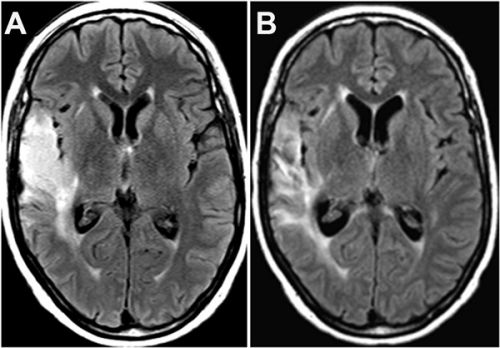

Hier een scanbeeld van de vrouw: tekst gaat verder onder beeld:

Op het moment van publicatie van haar case studie i december 2014 was de vrouw nog steeds kankervrij:

From December 2012 up to now (December 2014), the patient has remained in good health under exclusive POH inhalation therapy combined with TMZ schedule, without any evidence of tumor recurrence, and only taking anti-seizure medication but no steroidal drugs. Recent clinical laboratory analysis showed hematologic and biochemical parameters within normal range values, without any signs of neurologic, hepatic and renal toxicity or clinical adverse effects.

Het zal duidelijk zijn dat POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) met grote interesse wordt gevolgd in de wetenschappeljike wereld. Afgelopen week vroeg een patiente met een recidief van een Glioblastoma die afgelopen week is begonnen bij dr. Stefaan van Gool met een behandeling met immuuntherapie of ik dit middel kende want dr. van Gool had haar dit aanbevolen. Toevallig was ik net bezig met dit artikel dus heb haar nu ook dit allemaal toegestuurd.

Perrilyl Alcohol is een zogeheten RAS remmer, een natuurlijk niet toxisch middel dat gewonnen - geisoleerd wordt uit verschillende oliën uit verschillende planten en kruiden en fruit zoals citrusvruchten, kersen, lavendel, pepermunt, groene munt, veenbessen, gember en citroengras o.a. en als zodanig door een apotheker moet worden samengesteld.

Op deze website staat veel gedetailleerde informatie over POH (Monoterpene Perrlyl Alcohol) waarvan ik een en ander heb gebruikt voor bovenstaand artikel.

Andere studierapporten die ik gebruikt heb naast de al vernoemde zijn:

Ras pathway activation in gliomas: a strategic target for intranasal administration of perillyl alcohol

en

Perillyl alcohol and methyl jasmonate sensitize cancer cells to cisplatin

en

Long-term outcome in patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with Perillyl alcohol inhalation.

en

Correlation of tumor topography and peritumoral edema of recurrent malignant gliomas with therapeutic response to intranasal administration of perillyl alcohol

en

Intranasal Administration of Perillyl Alcohol Activates Peripheral and Bronchus-Associated Immune System In Vivo

en

Perillyl Alcohol and Its Drug-Conjugated Derivatives as Potential Novel Methods of Treating Brain Metastases

en

Monoterpene as a chemopreventive agent for regression of mammalian nervous system cell tumors, use of monoterpene for causing regression and inhibition of nervous system cell tumors, and method for administration of monoterpene perillyl alcohol

Hieronder de abstracten van Long-term outcome in patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with Perillyl alcohol inhalation

en van

Perillyl Alcohol and Its Drug-Conjugated Derivatives as Potential Novel Methods of Treating Brain Metastases

Met referentielijsten

From the large field of drug modifications aimed at the enhancement of BBB penetration, we presented NEO212, where temozolomide, a sub-optimally brain-targeting molecule, was conjugated to POH. Based on in silico prediction, as well as preclinical brain tumor and brain metastasis models, NEO212 appears to be a novel compound with great therapeutic promise.

Perillyl Alcohol and Its Drug-Conjugated Derivatives as Potential Novel Methods of Treating Brain Metastases

Dario Marchetti, Academic Editor

Abstract

Metastasis to the central nervous system remains difficult to treat, and such patients are faced with a dismal prognosis. The blood-brain barrier (BBB), despite being partially compromised within malignant lesions in the brain, still retains much of its barrier function and prevents most chemotherapeutic agents from effectively reaching the tumor cells. Here, we review some of the recent developments aimed at overcoming this obstacle in order to more effectively deliver chemotherapeutic agents to the intracranial tumor site. These advances include intranasal delivery to achieve direct nose-to-brain transport of anticancer agents and covalent modification of existing drugs to support enhanced penetration of the BBB. In both of these areas, use of the natural product perillyl alcohol, a monoterpene with anticancer properties, contributed to promising new results, which will be discussed here.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Over the past decade, better control of systemic neoplastic disease has resulted in prolonged survival of patients with advanced cancers. In combination with earlier detection of metastatic spread to the brain, however, these advances have led to progressively increasing prevalence of patients with brain metastasis, which threatens to compromise gains made in systemic therapy. The chemotherapeutic treatment of brain metastases is severely impeded by the presence of the BBB, which minimizes effective access of most cancer drugs to the sites of intracerebral lesions. Consequently, it is essential to find novel approaches to more effectively penetrate, or perhaps entirely circumvent, this significant obstacle.

In this context, we have presented examples of new approaches, derived from the experience with glioblastoma patients, which might become applicable to brain-metastatic patients, as well. Intranasal delivery of POH has yielded encouraging results in patients with primary brain cancer, and it is not unreasonable to rationalize that it should yield similar outcomes in patients with brain metastases. However, while clinical trials with intranasal POH have been initiated for recurrent glioblastoma patients in the United States, no such studies are currently being planned for patients with metastatic brain lesions.

From the large field of drug modifications aimed at the enhancement of BBB penetration, we presented NEO212, where temozolomide, a sub-optimally brain-targeting molecule, was conjugated to POH. Based on in silico prediction, as well as preclinical brain tumor and brain metastasis models, NEO212 appears to be a novel compound with great therapeutic promise. However, the validation of this prediction has to await testing of NEO212 in clinical trials, which have not yet started. Furthermore, based on the success of the intranasal delivery of POH, it might be intriguing to determine whether brain-targeted activity of the conjugated NEO212 compound could be increased even further via intranasal delivery, as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Glioma Research Group, an alliance of University of Southern California laboratories dedicated to developing new treatments for tumors of the CNS. Work in the authors’ labs was supported by the Hale Family Research Fund and Sounder Foundation (to Thomas C. Chen) and the California Breast Cancer Research Program (to Axel H. Schönthal).

Abbreviations

BBB: blood-brain barrier; CNS: central nervous system; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; IN: intranasal; LMC: leptomeningeal carcinomatosis; NEO212: perillyl alcohol conjugated to temozolomide; PBM: parenchymal brain metastasis; POH: perillyl alcohol; TMZ: temozolomide.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and editing of this manuscript and approved it for submission. The figures were generated by Axel H. Schönthal.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1.

Walker A.E., Robins M., Weinfeld F.D. Epidemiology of brain tumors: The national survey of intracranial neoplasms. Neurology. 1985;35:219–226. doi: 10.1212/WNL.35.2.219. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]2.

Percy A.K., Elveback L.R., Okazaki H., Kurland L.T. Neoplasms of the central nervous system. Epidemiologic considerations. Neurology. 1972;22:40–48. doi: 10.1212/WNL.22.1.40. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]3.

Gavrilovic I.T., Posner J.B. Brain metastases: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. J. Neurooncol. 2005;75:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-8093-6. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]4.

Miller K.D., Weathers T., Haney L.G., Timmerman R., Dickler M., Shen J., Sledge G.W., Jr. Occult central nervous system involvement in patients with metastatic breast cancer: Prevalence, predictive factors and impact on overall survival. Ann. Oncol. 2003;14:1072–1077. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg300. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]5.

Nayak L., Lee E.Q., Wen P.Y. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2012;14:48–54. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0203-y. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]6.

Posner J.B., Chernik N.L. Intracranial metastases from systemic cancer. Adv. Neurol. 1978;19:579–592. [PubMed]7.

Tsukada Y., Fouad A., Pickren J.W., Lane W.W. Central nervous system metastasis from breast carcinoma autopsy study. Cancer. 1983;52:2349–2354. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19831215)52:12<2349::AID-CNCR2820521231>3.0.CO;2-B. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]8.

Davis F.G., Dolecek T.A., McCarthy B.J., Villano J.L. Toward determining the lifetime occurrence of metastatic brain tumors estimated from 2007 United States cancer incidence data. Neuro-Oncology. 2012;14:1171–1177. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]9.

Steeg P.S., Camphausen K.A., Smith Q.R. Brain metastases as preventive and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:352–363. doi: 10.1038/nrc3053. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]10. Choy C., Neman J. Role of Blood-Brain Barrier, Choroid Plexus, and Cerebral Spinal Fluid in Extravasation and Colonization of Brain Metastases. In: Neman J., Chen T.C., editors. The Choroid Plexus and Cerebrospinal Fluid—Emerging Roles in CNS Development, Maintenance, and Disease Progression. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2016. pp. 77–102.

11.

Demopoulos A. Leptomeningeal metastases. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2004;4:196–204. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0039-z. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]12.

Banks W.A. From blood-brain barrier to blood-brain interface: New opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016;15:275–292. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.21. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]13.

Schouten L.J., Rutten J., Huveneers H.A., Twijnstra A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2698–2705. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10541. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]14.

Drappatz J., Batchelor T.T. Leptomeningeal neoplasms. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2007;9:283–293. doi: 10.1007/s11940-007-0014-5. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]15.

Le Rhun E., Taillibert S., Chamberlain M.C. Carcinomatous meningitis: Leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013;4(Suppl. S4):S265–S288. [PMC free article] [PubMed]16.

Lee D.W., Lee K.H., Kim J.W., Keam B. Molecular Targeted Therapies for the Treatment of Leptomeningeal Carcinomatosis: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1074. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071074. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]17.

Mack F., Baumert B.G., Schafer N., Hattingen E., Scheffler B., Herrlinger U., Glas M. Therapy of leptomeningeal metastasis in solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016;43:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.12.004. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]18.

Nussbaum E.S., Djalilian H.R., Cho K.H., Hall W.A. Brain metastases: Histology, multiplicity, surgery, and survival. Cancer. 1996;78:1781–1788. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19961015)78:8<1781::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-U. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]19.

Quigley M.R., Fukui O., Chew B., Bhatia S., Karlovits S. The shifting landscape of metastatic breast cancer to the CNS. Neurosurg. Rev. 2013;36:377–382. doi: 10.1007/s10143-012-0446-6. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]20.

Fidler I.J. The role of the organ microenvironment in brain metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2011;21:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.12.009. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]21.

Patel R.R., Mehta M.P. Targeted therapy for brain metastases: Improving the therapeutic ratio. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:1675–1683. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2489. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]22.

Patil C.G., Pricola K., Sarmiento J.M., Garg S.K., Bryant A., Black K.L. Whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) alone versus WBRT and radiosurgery for the treatment of brain metastases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;6:CD006121. [PubMed]23.

Bartsch R., Berghoff A.S., Preusser M. Optimal management of brain metastases from breast cancer. Issues and considerations. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s40263-012-0024-z. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]24.

Nieder C., Grosu A.L., Gaspar L.E. Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for brain metastases: A systematic review. Radiat. Oncol. 2014;9:155. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]25.

Stupp R., Hegi M.E., Mason W.P., van den Bent M.J., Taphoorn M.J., Janzer R.C., Ludwin S.K., Allgeier A., Fisher B., Belanger K., et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-Year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]26.

Zhu W., Zhou L., Qian J.Q., Qiu T.Z., Shu Y.Q., Liu P. Temozolomide for treatment of brain metastases: A review of 21 clinical trials. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;5:19–27. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i1.19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]27.

Cao K.I., Lebas N., Gerber S., Levy C., Le Scodan R., Bourgier C., Pierga J.Y., Gobillion A., Savignoni A., Kirova Y.M. Phase II randomized study of whole-brain radiation therapy with or without concurrent temozolomide for brain metastases from breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2015;26:89–94. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu488. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]28.

Tatar Z., Thivat E., Planchat E., Gimbergues P., Gadea E., Abrial C., Durando X. Temozolomide and unusual indications: Review of literature. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;39:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.06.002. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]29.

Palmieri D., Duchnowska R., Woditschka S., Hua E., Qian Y., Biernat W., Sosinska-Mielcarek K., Gril B., Stark A.M., Hewitt S.M., et al. Profound prevention of experimental brain metastases of breast cancer by temozolomide in an MGMT-dependent manner. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:2727–2739. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]30.

Deeken J.F., Loscher W. The blood-brain barrier and cancer: Transporters, treatment, and Trojan horses. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:1663–1674. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2854. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]31.

Yonemori K., Tsuta K., Ono M., Shimizu C., Hirakawa A., Hasegawa T., Hatanaka Y., Narita Y., Shibui S., Fujiwara Y. Disruption of the blood brain barrier by brain metastases of triple-negative and basal-type breast cancer but not HER2/neu-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:302–308. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24735. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]32.

Boogerd W., Dalesio O., Bais E.M., van der Sande J.J. Response of brain metastases from breast cancer to systemic chemotherapy. Cancer. 1992;69:972–980. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920215)69:4<972::AID-CNCR2820690423>3.0.CO;2-P. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]33.

Boogerd W., Groenveld F., Linn S., Baars J.W., Brandsma D., van Tinteren H. Chemotherapy as primary treatment for brain metastases from breast cancer: Analysis of 115 one-year survivors. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2012;138:1395–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1218-y. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]34.

Franciosi V., Cocconi G., Michiara M., di Costanzo F., Fosser V., Tonato M., Carlini P., Boni C., di Sarra S. Front-line chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide for patients with brain metastases from breast carcinoma, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma, or malignant melanoma: A prospective study. Cancer. 1999;85:1599–1605. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990401)85:7<1599::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-#. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]35.

Lockman P.R., Mittapalli R.K., Taskar K.S., Rudraraju V., Gril B., Bohn K.A., Adkins C.E., Roberts A., Thorsheim H.R., Gaasch J.A., et al. Heterogeneous blood-tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:5664–5678. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]36.

Ostermann S., Csajka C., Buclin T., Leyvraz S., Lejeune F., Decosterd L.A., Stupp R. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid population pharmacokinetics of temozolomide in malignant glioma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:3728–3736. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0807. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]37.

Arslan C., Dizdar O., Altundag K. Systemic treatment in breast-cancer patients with brain metastasis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2010;11:1089–1100. doi: 10.1517/14656561003702412. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]38.

Leone J.P., Leone B.A. Breast cancer brain metastases: The last frontier. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2015;4:33. doi: 10.1186/s40164-015-0028-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]39.

Lim E., Lin N.U. Updates on the management of breast cancer brain metastases. Oncology. 2014;28:572–578. [PubMed]40.

Dickson P.I. Novel treatments and future perspectives: Outcomes of intrathecal drug delivery. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;47(Suppl. S1):S124–S127. [PubMed]41.

Aiello-Laws L., Rutledge D.N. Management of adult patients receiving intraventricular chemotherapy for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastasis. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2008;12:429–435. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.429-435. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]42.

Upadhyay R.K. Drug delivery systems, CNS protection, and the blood brain barrier. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014:869269. doi: 10.1155/2014/869269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]43.

Loureiro J.A., Gomes B., Coelho M.A., do Carmo Pereira M., Rocha S. Targeting nanoparticles across the blood-brain barrier with monoclonal antibodies. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:709–722. doi: 10.2217/nnm.14.27. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]44.

Larsen J.M., Martin D.R., Byrne M.E. Recent advances in delivery through the blood-brain barrier. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014;14:1148–1160. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140329230311. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]45.

Pardridge W.M. Drug transport across the blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1959–1972. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]46.

Illum L. Nasal drug delivery—Recent developments and future prospects. J. Control. Release. 2012;161:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.024. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]47.

Gizurarson S. Anatomical and histological factors affecting intranasal drug and vaccine delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2012;9:566–582. doi: 10.2174/156720112803529828. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]48.

Wolfe T.R., Bernstone T. Intranasal drug delivery: An alternative to intravenous administration in selected emergency cases. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2004;30:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2004.01.006. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]49.

Bitter C., Suter-Zimmermann K., Surber C. Nasal drug delivery in humans. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2011;40:20–35. [PubMed]50.

Ugwoke M.I., Agu R.U., Verbeke N., Kinget R. Nasal mucoadhesive drug delivery: Background, applications, trends and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57:1640–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.009. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]51.

Merkus F.W., van den Berg M.P. Can nasal drug delivery bypass the blood-brain barrier? Questioning the direct transport theory. Drugs R D. 2007;8:133–144. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200708030-00001. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]52.

Kozlovskaya L., Abou-Kaoud M., Stepensky D. Quantitative analysis of drug delivery to the brain via nasal route. J. Control. Release. 2014;189:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.053. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]53.

Dhuria S.V., Hanson L.R., Frey W.H., II Intranasal delivery to the central nervous system: Mechanisms and experimental considerations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;99:1654–1673. doi: 10.1002/jps.21924. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]54.

Lochhead J.J., Thorne R.G. Intranasal delivery of biologics to the central nervous system. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:614–628. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.002. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]55.

Djupesland P.G., Messina J.C., Mahmoud R.A. The nasal approach to delivering treatment for brain diseases: An anatomic, physiologic, and delivery technology overview. Ther. Deliv. 2014;5:709–733. doi: 10.4155/tde.14.41. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]56.

Pardeshi C.V., Belgamwar V.S. Direct nose to brain drug delivery via integrated nerve pathways bypassing the blood-brain barrier: An excellent platform for brain targeting. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013;10:957–972. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.790887. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]57.

Badhan R.K., Kaur M., Lungare S., Obuobi S. Improving brain drug targeting through exploitation of the nose-to-brain route: A physiological and pharmacokinetic perspective. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2014;11:458–471. doi: 10.2174/1567201811666140321113555. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]58.

Van Woensel M., Wauthoz N., Rosiere R., Amighi K., Mathieu V., Lefranc F., van Gool S.W., de Vleeschouwer S. Formulations for Intranasal Delivery of Pharmacological Agents to Combat Brain Disease: A New Opportunity to Tackle GBM? Cancers. 2013;5:1020–1048. doi: 10.3390/cancers5031020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]59.

Jansson B., Bjork E. Visualization of in vivo olfactory uptake and transfer using fluorescein dextran. J. Drug Target. 2002;10:379–386. doi: 10.1080/1061186021000001823. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]60.

Leopold D.A. The relationship between nasal anatomy and human olfaction. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:1232–1238. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198811000-00015. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]61.

Jafek B.W. Ultrastructure of human nasal mucosa. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1576–1599. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198312000-00011. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]62.

Lledo P.M., Gheusi G., Vincent J.D. Information processing in the mammalian olfactory system. Phys. Rev. 2005;85:281–317. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2004. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]63.

Thorne R.G., Pronk G.J., Padmanabhan V., Frey W.H., II Delivery of insulin-like growth factor-I to the rat brain and spinal cord along olfactory and trigeminal pathways following intranasal administration. Neuroscience. 2004;127:481–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.029. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]64.

Johnson N.J., Hanson L.R., Frey W.H. Trigeminal pathways deliver a low molecular weight drug from the nose to the brain and orofacial structures. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:884–893. doi: 10.1021/mp100029t. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]65.

Hanson L.R., Frey W.H., II Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9(Suppl. S3):1463 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S3-S5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]66.

Gomez D., Martinez J.A., Hanson L.R., Frey W.H., II, Toth C.C. Intranasal treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and stroke. Front. Biosci. 2012;4:74–89. doi: 10.2741/s252. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]67.

Jiang Y., Li Y., Liu X. Intranasal delivery: Circumventing the iron curtain to treat neurological disorders. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1717–1725. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1065812. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]68.

Kalviainen R. Intranasal therapies for acute seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.027. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]69.

Mittal D., Ali A., Md S., Baboota S., Sahni J.K., Ali J. Insights into direct nose to brain delivery: Current status and future perspective. Drug Deliv. 2014;21:75–86. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.838713. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]70.

Craft S., Baker L.D., Montine T.J., Minoshima S., Watson G.S., Claxton A., Arbuckle M., Callaghan M., Tsai E., Plymate S.R., et al. Intranasal insulin therapy for Alzheimer disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A pilot clinical trial. Arch. Neurol. 2012;69:29–38. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]71.

Salameh T.S., Bullock K.M., Hujoel I.A., Niehoff M.L., Wolden-Hanson T., Kim J., Morley J.E., Farr S.A., Banks W.A. Central Nervous System Delivery of Intranasal Insulin: Mechanisms of Uptake and Effects on Cognition. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:715–728. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150307. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]72.

Aly A.E., Waszczak B.L. Intranasal gene delivery for treating Parkinson’s disease: Overcoming the blood-brain barrier. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015;12:1923–1941. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1069815. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]73.

Mohanty C., Kundu P., Sahoo S.K. Brain Targeting of siRNA via Intranasal Pathway. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015;21:4606–4613. doi: 10.2174/138161282131151013191737. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]74.

Wolf D.A., Hanson L.R., Aronovich E.L., Nan Z., Low W.C., Frey W.H., II, McIvor R.S. Lysosomal enzyme can bypass the blood-brain barrier and reach the CNS following intranasal administration. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.02.006. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]75.

Jiang Y., Zhu J., Xu G., Liu X. Intranasal delivery of stem cells to the brain. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011;8:623–632. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.566267. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]76.

Li Y.H., Feng L., Zhang G.X., Ma C.G. Intranasal delivery of stem cells as therapy for central nervous system disease. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015;98:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.01.016. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]77.

Chen X.Q., Fawcett J.R., Rahman Y.E., Ala T.A., Frey I.W. Delivery of Nerve Growth Factor to the Brain via the Olfactory Pathway. J. Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1:35–44. [PubMed]78.

Fliedner S., Schulz C., Lehnert H. Brain uptake of intranasally applied radioiodinated leptin in Wistar rats. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2088–2094. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1016. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]79.

Born J., Lange T., Kern W., McGregor G.P., Bickel U., Fehm H.L. Sniffing neuropeptides: A transnasal approach to the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:514–516. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-849. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]80.

Wang F., Jiang X., Lu W. Profiles of methotrexate in blood and CSF following intranasal and intravenous administration to rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;263:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(03)00341-7. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]81.

Stevens J., Ploeger B.A., van der Graaf P.H., Danhof M., de Lange E.C. Systemic and direct nose-to-brain transport pharmacokinetic model for remoxipride after intravenous and intranasal administration. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2011;39:2275–2282. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040782. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]82.

Serwer L.P., James C.D. Challenges in drug delivery to tumors of the central nervous system: An overview of pharmacological and surgical considerations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.004. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]83.

Peterson A., Bansal A., Hofman F., Chen T.C., Zada G. A systematic review of inhaled intranasal therapy for central nervous system neoplasms: An emerging therapeutic option. J. Neurooncol. 2014;116:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1346-5. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]84.

Wang D., Gao Y., Yun L. Study on brain targeting of raltitrexed following intranasal administration in rats. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2006;57:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0018-3. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]85.

Shingaki T., Hidalgo I.J., Furubayashi T., Katsumi H., Sakane T., Yamamoto A., Yamashita S. The transnasal delivery of 5-fluorouracil to the rat brain is enhanced by acetazolamide (the inhibitor of the secretion of cerebrospinal fluid) Int. J. Pharm. 2009;377:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.05.009. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]86.

Sakane T., Yamashita S., Yata N., Sezaki H. Transnasal delivery of 5-fluorouracil to the brain in the rat. J. Drug Target. 1999;7:233–240. doi: 10.3109/10611869909085506. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]87.

Shingaki T., Inoue D., Furubayashi T., Sakane T., Katsumi H., Yamamoto A., Yamashita S. Transnasal delivery of methotrexate to brain tumors in rats: A new strategy for brain tumor chemotherapy. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:1561–1568. doi: 10.1021/mp900275s. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]88.

Blakeley J.O., Olson J., Grossman S.A., He X., Weingart J., Supko J.G., New Approaches to Brain Tumor Therapy (NABTT) Consortium Effect of blood brain barrier permeability in recurrent high grade gliomas on the intratumoral pharmacokinetics of methotrexate: A microdialysis study. J. Neurooncol. 2009;91:51–58. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9678-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]89.

Hashizume R., Ozawa T., Gryaznov S.M., Bollen A.W., Lamborn K.R., Frey W.H., II, Deen D.F. New therapeutic approach for brain tumors: Intranasal delivery of telomerase inhibitor GRN163. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10:112–120. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-052. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]90.

Taki H., Kanazawa T., Akiyama F., Takashima Y., Okada H. Intranasal delivery of camptothecin-loaded Tat-modified nanomicells for treatment of intracranial brain tumors. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:1092–1102. doi: 10.3390/ph5101092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]91.

Djupesland P.G. Nasal drug delivery devices: Characteristics and performance in a clinical perspective—A review. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2013;3:42–62. doi: 10.1007/s13346-012-0108-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]92. Crowell P.L., Elson C.E. Isoprenoids, Health and Disease. In: Wildman R.E.C., editor. Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2001. pp. 31–54.

93.

Haag J.D., Gould M.N. Mammary carcinoma regression induced by perillyl alcohol, a hydroxylated analog of limonene. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1994;34:477–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00685658. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]94.

Mills J.J., Chari R.S., Boyer I.J., Gould M.N., Jirtle R.L. Induction of apoptosis in liver tumors by the monoterpene perillyl alcohol. Cancer Res. 1995;55:979–983. [PubMed]95.

Ong T.P., Cardozo M.T., de Conti A., Moreno F.S. Chemoprevention of hepatocarcinogenesis with dietary isoprenic derivatives: Cellular and molecular aspects. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:1173–1190. [PubMed]96.

Stark M.J., Burke Y.D., McKinzie J.H., Ayoubi A.S., Crowell P.L. Chemotherapy of pancreatic cancer with the monoterpene perillyl alcohol. Cancer Lett. 1995;96:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03912-G. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]97.

Yuri T., Danbara N., Tsujita-Kyutoku M., Kiyozuka Y., Senzaki H., Shikata N., Kanzaki H., Tsubura A. Perillyl alcohol inhibits human breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004;84:251–260. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000019966.97011.4d. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]98.

Teruszkin Balassiano I., Alves de Paulo S., Henriques Silva N., Curie Cabral M., Gibaldi D., Bozza M., Orlando da Fonseca C., Da Gloria da Costa Carvalho M. Effects of perillyl alcohol in glial C6 cell line in vitro and anti-metastatic activity in chorioallantoic membrane model. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002;10:785–788. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.10.6.785. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]99.

Azzoli C.G., Miller V.A., Ng K.K., Krug L.M., Spriggs D.R., Tong W.P., Riedel E.R., Kris M.G. A phase I trial of perillyl alcohol in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2003;51:493–498. [PubMed]100.

Bailey H.H., Attia S., Love R.R., Fass T., Chappell R., Tutsch K., Harris L., Jumonville A., Hansen R., Shapiro G.R., et al. Phase II trial of daily oral perillyl alcohol (NSC 641066) in treatment-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2008;62:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0585-6. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]101.

Bailey H.H., Wilding G., Tutsch K.D., Arzoomanian R.Z., Alberti D., Feierabend C., Simon K., Marnocha R., Holstein S.A., Stewart J., et al. A phase I trial of perillyl alcohol administered four times daily for 14 days out of 28 days. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2004;54:368–376. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0788-z. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]102.

Liu G., Oettel K., Bailey H., Ummersen L.V., Tutsch K., Staab M.J., Horvath D., Alberti D., Arzoomanian R., Rezazadeh H., et al. Phase II trial of perillyl alcohol (NSC 641066) administered daily in patients with metastatic androgen independent prostate cancer. Investig. New Drugs. 2003;21:367–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1025437115182. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]103.

Morgan-Meadows S., Dubey S., Gould M., Tutsch K., Marnocha R., Arzoomanin R., Alberti D., Binger K., Feierabend C., Volkman J., et al. Phase I trial of perillyl alcohol administered four times daily continuously. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2003;52:361–366. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0684-y. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]104.

Murren J.R., Pizzorno G., DiStasio S.A., McKeon A., Peccerillo K., Gollerkari A., McMurray W., Burtness B.A., Rutherford T., Li X., et al. Phase I study of perillyl alcohol in patients with refractory malignancies. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002;1:130–135. doi: 10.4161/cbt.57. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]105.

Ripple G.H., Gould M.N., Arzoomanian R.Z., Alberti D., Feierabend C., Simon K., Binger K., Tutsch K.D., Pomplun M., Wahamaki A., et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of perillyl alcohol administered four times a day. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000;6:390–396. [PubMed]106.

Chen T.C., Fonseca C.O., Schönthal A.H. Preclinical development and clinical use of perillyl alcohol for chemoprevention and cancer therapy. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015;5:1580–1593. [PMC free article] [PubMed]107.

Cho H.Y., Wang W., Jhaveri N., Torres S., Tseng J., Leong M.N., Lee D.J., Goldkorn A., Xu T., Petasis N.A., et al. Perillyl alcohol for the treatment of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2462–2472. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0321. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]108.

Stupp R., Mason W.P., van den Bent M.J., Weller M., Fisher B., Taphoorn M.J., Belanger K., Brandes A.A., Marosi C., Bogdahn U., et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]109.

Da Fonseca C.O., Schwartsmann G., Fischer J., Nagel J., Futuro D., Quirico-Santos T., Gattass C.R. Preliminary results from a phase I/II study of perillyl alcohol intranasal administration in adults with recurrent malignant gliomas. Surg. Neurol. 2008;70:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.07.040. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]110.

Da Fonseca C.O., Teixeira R.M., Silva J.C., de Saldanha da Gama Fischer J., Meirelles O.C., Landeiro J.A., Quirico-Santos T. Long-term outcome in patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with perillyl alcohol inhalation. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5625–5631. [PubMed]111. Da Fonseca C.O., Quirico-Santos T. Perillyl Alcohol: A Pharmacotherapeutic Report. In: de Sousa D.P., editor. Bioactive Essential Oils and Cancer. Springer International Publishing Switzerland; Heidelberg, Germany: New York, NY, USA: London, UK: 2015. pp. 267–288.

112.

Da Fonseca C.O., Simao M., Lins I.R., Caetano R.O., Futuro D., Quirico-Santos T. Efficacy of monoterpene perillyl alcohol upon survival rate of patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2011;137:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0873-0. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]113.

Pajouhesh H., Lenz G.R. Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. NeuroRx. 2005;2:541–553. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]114.

Chen Y., Liu L. Modern methods for delivery of drugs across the blood-brain barrier. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:640–665. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.010. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]115.

Vastag M., Keseru G.M. Current in vitro and in silico models of blood-brain barrier penetration: A practical view. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2009;12:115–124. [PubMed]116.

Geldenhuys W.J., Mohammad A.S., Adkins C.E., Lockman P.R. Molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier permeation. Ther. Deliv. 2015;6:961–971. doi: 10.4155/tde.15.32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]117.

Goodwin J.T., Clark D.E. In silico predictions of blood-brain barrier penetration: Considerations to “keep in mind” J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005;315:477–483. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075705. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]118.

Mehdipour A.R., Hamidi M. Brain drug targeting: A computational approach for overcoming blood-brain barrier. Drug Discov. Today. 2009;14:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.07.009. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]119.

Lanevskij K., Japertas P., Didziapetris R., Petrauskas A. Ionization-specific prediction of blood-brain permeability. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;98:122–134. doi: 10.1002/jps.21405. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]120.

Christodoulou C., Bafaloukos D., Kosmidis P., Samantas E., Bamias A., Papakostas P., Karabelis A., Bacoyiannis C., Skarlos D.V. Phase II study of temozolomide in heavily pretreated cancer patients with brain metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2001;12:249–254. doi: 10.1023/A:1008354323167. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]121.

Abrey L.E., Olson J.D., Raizer J.J., Mack M., Rodavitch A., Boutros D.Y., Malkin M.G. A phase II trial of temozolomide for patients with recurrent or progressive brain metastases. J. Neurooncol. 2001;53:259–265. doi: 10.1023/A:1012226718323. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]122.

Trudeau M.E., Crump M., Charpentier D., Yelle L., Bordeleau L., Matthews S., Eisenhauer E. Temozolomide in metastatic breast cancer (MBC): A phase II trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada—Clinical Trials Group (NCIC-CTG) Ann. Oncol. 2006;17:952–956. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl056. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]123.

Addeo R., de Rosa C., Faiola V., Leo L., Cennamo G., Montella L., Guarrasi R., Vincenzi B., Caraglia M., del Prete S. Phase 2 trial of temozolomide using protracted low-dose and whole-brain radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer and breast cancer patients with brain metastases. Cancer. 2008;113:2524–2531. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23859. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]124.

Siena S., Crino L., Danova M., Del Prete S., Cascinu S., Salvagni S., Schiavetto I., Vitali M., Bajetta E. Dose-dense temozolomide regimen for the treatment of brain metastases from melanoma, breast cancer, or lung cancer not amenable to surgery or radiosurgery: A multicenter phase II study. Ann. Oncol. 2010;21:655–661. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]125.

Addeo R., Sperlongano P., Montella L., Vincenzi B., Carraturo M., Iodice P., Russo P., Parlato C., Salzano A., Cennamo G., et al. Protracted low dose of oral vinorelbine and temozolomide with whole-brain radiotherapy in the treatment for breast cancer patients with brain metastases. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012;70:603–609. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1945-4. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]126.

Cho H.Y., Wang W., Jhaveri N., Lee D.J., Sharma N., Dubeau L., Schönthal A.H., Hofman F.M., Chen T.C. NEO212, temozolomide conjugated to perillyl alcohol, is a novel drug for effective treatment of a broad range of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2004–2017. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0964. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]127.

Chen T.C., Cho H.Y., Wang W., Barath M., Sharma N., Hofman F.M., Schönthal A.H. A novel temozolomide-perillyl alcohol conjugate exhibits superior activity against breast cancer cells in vitro and intracranial triple-negative tumor growth in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:1181–1193. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0882. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]128. Wang W., Swenson S., Hofman F.M., Schönthal A.H., Chen T.C. Brain/plasma ratios of NEO212 in vivo. 2016. Unpublished work.

Articles from International Journal of Molecular Sciences are provided here courtesy of Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI)

We demonstrated that intranasal administration of a p21-Ras lipophilic inhibitor that easily crosses the blood-brain barrier is a safe and non-invasive strategy capable to prolong overall survival of patients with recurrent malignant glioma considered to be at terminal stage.

Long-term Outcome in Patients with Recurrent Malignant Glioma Treated with Perillyl Alcohol Inhalation

- CLOVIS O. DA FONSECA1,

- RAPHAEL M. TEIXEIRA2,

- JÚLIO CESAR T. SILVA3,

- JULIANA DE SALDANHA DA GAMA FISCHER4,

- OSÓRIO C. MEIRELLES5,

- JOSE ALBERTO LANDEIRO1 and

- THEREZA QUIRICO-SANTOS2⇑

+ Author Affiliations

- 1Department of General and Specialized Surgery, Antonio Pedro University Hospital, Fluminense Federal University, Niteroi, RJ, Brazil

- 2Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Institute of Biology, Fluminense Federal University, Niteroi, RJ, Brazil

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, Ipanema Federal Hospital, Ipanema, RJ, Brazil

- 4Laboratory for Proteomics and Protein Engineering, Carlos Chagas Institute, Fiocruz/Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

- 5Rio de Janeiro Federal University, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

- Correspondence to: Thereza Quirico-Santos, Laboratory of Cellular Pathology, Institute of Biology, Fluminense Federal University, Niteroi, RJ, 24020-141, Brazil. Tel: +55 2126292305, Fax: +55 2126292268, e-mail: tquirico@vm.uff.br

Abstract

Aim: This retrospective study aimed to evaluate the long-term response and toxicity of recurrent malignant glioma patients to inhalation chemotherapy with perillyl alcohol (POH). Patients and Methods: The cohort included 117 men and 81 women with primary glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; n=154), grade III astrocytoma (AA; n=26) and anaplastic oligodendroglioma (AO; n=5). POH inhalation schedule 4-times daily started with 66.7 mg/dose; 266 mg/day and escalated up to 133.4 mg/dose; 533.6 mg/day. Clinical toxicity and overall survival following treatment were compared with tumor size, topography, extent of peritumoral edema and histological classification. Results: Adhesion to the protocol was high (>95%), POH (533.6 mg/daily) occasionally caused nose soreness but rarely nosebleed. Tumor size, peritumoral edema and the oligodendroglial component influenced response to treatment. Conclusion: After 4 years under exclusive POH treatment, 19% of patients still remain in clinical remission. Long-term POH inhalation chemotherapy is a safe and non-invasive strategy efficient for recurrent malignant glioma.

References

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

-

- ↵

-

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

- ↵

overall overleving, hersentumoren, temodal, temozomide, Astrocytomen, Glioblastomen, monoterpene perillyl alcohol, complementair, niet-toxisch

Gerelateerde artikelen

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Monoterpene perillyl alcohol een natuurlijk middel verlengt overall overleving en ziektevrije tijd bij hersentumoren Glioblastoma hoog significant, vooral bij recidief van glioblastoma"