Aan dit artikel is vele uren gewerkt. Opzoeken, vertalen, op de website plaatsen enz. Als u ons wilt ondersteunen dan kan dat via een al of niet anonieme donatie. Elk bedrag is welkom hoe klein ook. Klik hier als u ons wilt helpen kanker-actueel online te houden Wij zijn een ANBI organisatie en dus is uw donatie in principe aftrekbaar voor de belasting.

8 augustus 2022: lees ook dit artikel: https://kanker-actueel.nl/vitamine-c-hoog-gedoseerd-naast-chemo-folfox-bevacizumab-geeft-in-vergelijking-met-alleen-chemo-statistisch-significant-verschil-in-mediane-overall-overleving-bij-inoperabele-onbehandelde-uitgezaaide-darmkanker-met-ras-mutatie.html

19 juni 2015: Bron: Integr Cancer Ther. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 Jul 4

Aanvullende niet-toxische ondersteuning zoals bv. aangepaste voeding plus extra vitamines waar nodig, Chinese kruiden, acupunctuur, yoga, Qi-Gong, beweging / sporten enz. naast reguliere behandelingen zoals operatie, chemo en bestraling, voor patiënten met darmkanker in alle stadia, gegeven onder deskundige begeleiding zorgt voor een veel grotere 5-jaars overleving en veel minder kans op overlijden voor alle oorzaken. Alles werd vergeleken met overlijdens statistieken uit de Kaiser Permanente Northern California registries en de California Cancer Registries die dienden als controlegroepen.

Dit blijkt uit een langjarige studie uitgevoerd in een speciale kliniek voor complementaire geneeskunde met als basis TCM, traditionele Chinese geneeswijzen waarbij voeding, beweging, acupunctuur, Qi-Gong, Yoga enz. werd gegeven onder deskundige begeleiding waar nodig.

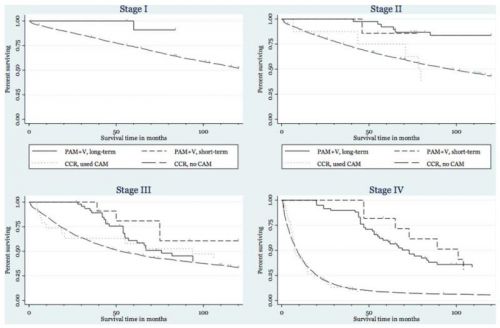

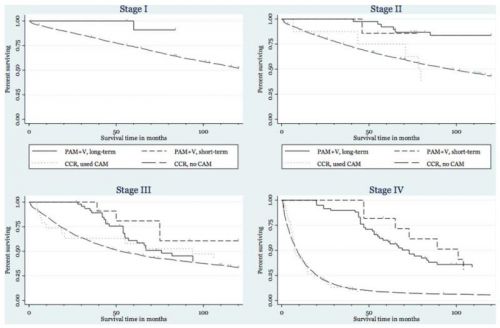

De studie is geanalyseerd en onderverdeeld in:

- deelresultaten voor complementaire ondersteuning (PAM+V) op korte termijn en complementaire ondersteuning (PAM+V) op korte termijn plus lange termijn.

- Ook zijn de resultaten onderverdeeld in de verschillende stadia bij diagnose, darmkanker stadium I, darmkanker stadium II, darmkanker stadium III, en darmkanker stadium IV.

- De complementaire ondersteuning bestond o.a. uit voedingsadviezen, gericht bewegen onder deskundige begeleiding waar nodig, TCM - Chinese kruiden plus eventueel aanvullende vitamines enz., yoga, Qi-Gong, acupunctuur enz. Zie in studierapport de gebruikte ondersteuning.

Algemeen bleek de complementaire ondersteuning (PAM+V) aanvullend op een conventionele reguliere aanpak volgens de richtlijnen het risico op overlijden voor alle oorzaken te verminderen na 10 jaar follow-up:

- voor stadium I met 95%, voor stadium II met 64%, stadium III met 29%, en stadium IV met 75%.

- Er was geen significant statistisch verschil tussen korte termijn en lange termijn ondersteuning.

Conclusie: Met een verschil op 5 jaar van 512% en 52% tussen PAM-V lange termijn (60%, en de controlegroepen resp. 7% en 8% blijkt aanvullende niet-toxische ondersteuning - PAM+V - met conventionele reguliere behandelingen sterk de overleving voor darmkankerpatiënten in alle stadia te verbeteren.

Overall overlevingscijfers op 1, 2 en 5 jaar voor combinatie PAM-V korte termijn en lange termijn samen in vergelijking met de statitische cijfers uit de twee verschillende registraties, Kaiser Permanente Northern California registries - Kaiser en de California Cancer Registries - CCR:

- Darmkanker stadium stadium I:

na 1 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 95%, CCR 93%

na 2 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%. Kaiser 92%, CCR 88%

na 5 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 81%, CCR 74%

- Darmkanker stadium II:

na 1 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 93%, CCR 89%

na 2 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 86%, CCR 81%

na 5 jaar PAM-V lange termijn 92%, PAM-V korte termijn 86%, Kaiser 65%, CCR 63%

- Darmkanker stadium III:

na 1 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 91%, CCR 83%

na 2 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 78%, CCR 69%

na 5 jaar PAM-V lange termijn 61%, PAM-V korte termijn 80%, Kaiser 52%, CCR 48%

- Darmkanker stadium IV:

na 1 jaar PAM-V korte + lange termijn 100%, Kaiser 44%, CCR 40%

na 2 jaar PAM-V lange termijn 93%, PAM-V korte termijn 100%, Kaiser 25%, CCR 20%

na 5 jaar PAM-V lange termijn 60%, PAM-V korte termijn 82%, Kaiser 7%, CCR 8%

Het studierapport: Colon Cancer Survival With Herbal Medicine and Vitamins Combined With Standard Therapy in a Whole-Systems Approach: Ten-Year Follow-up Data Analyzed With Marginal Structural Models and Propensity Score Methods is gratis in te zien. Met heel goed beschreven hoe tte werk is gegaan enz. Het is dan weliswaar geen gerandomiserde dubbelblinde studie maar wel een studie met een gedegen opzet en ook peer reviewed gepubliceerd.

Neem dit studierapport inclusief refenrentielijst mee naar uw behandelend artsen, zowel regulier als complementair werkende artsen en/of raadpleeg onze studielijst van complementaire aanpak bij darmkanker, zie gerelateerde artikelen.

Hier het abstract van de studie:

Combining PAM+V with conventional therapy improved survival, compared with conventional therapy alone, suggesting that prospective trials combining PAM+V with conventional therapy for colorectal cancer in all stages are justified.

Integr Cancer Ther. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 Jul 4.

Published in final edited form as:

PMCID: PMC4081504

NIHMSID: NIHMS603965

Colon Cancer Survival With Herbal Medicine and Vitamins Combined With Standard Therapy in a Whole-Systems Approach: Ten-Year Follow-up Data Analyzed With Marginal Structural Models and Propensity Score Methods

Michael McCulloch, LAc, MPH, PhD,

1,2 Michael Broffman, LAc,

1 Mark van der Laan, PhD,

2 Alan Hubbard, PhD,

2 Lawrence Kushi, DSc,

3 Donald I. Abrams, MD,

4 Jin Gao, MD, PhD,

5 and

John M. Colford, Jr, MD, PhD

2

See other articles in PMC that

cite the published article.

Abstract

Although localized colon cancer is often successfully treated with surgery, advanced disease requires aggressive systemic therapy that has lower effectiveness. Approximately 30% to 75% of patients with colon cancer use complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), but there is limited formal evidence of survival efficacy. In a consecutive case series with 10-year follow-up of all colon cancer patients (n = 193) presenting at a San Francisco Bay-Area center for Chinese medicine (Pine Street Clinic, San Anselmo, CA), the authors compared survival in patients choosing short-term treatment lasting the duration of chemotherapy/radiotherapy with those continuing long-term. To put these data into the context of treatment responses seen in conventional medical practice, they also compared survival with Pan-Asian medicine + vitamins (PAM+V) with that of concurrent external controls from Kaiser Permanente Northern California and California Cancer Registries. Kaplan-Meier, traditional Cox regression, and more modern methods were used for causal inference—namely, propensity score and marginal structural models (MSMs), which have not been used before in studies of cancer survival and Chinese herbal medicine. PAM+V combined with conventional therapy, compared with conventional therapy alone, reduced the risk of death in stage I by 95%, stage II by 64%, stage III by 29%, and stage IV by 75%. There was no significant difference between short-term and long-term PAM+V. Combining PAM+V with conventional therapy improved survival, compared with conventional therapy alone, suggesting that prospective trials combining PAM+V with conventional therapy are justified.

References

1.

Jemal A, Siegel R, et al. Cancer statistics. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2008;58(2):71–96. [PubMed]2.

Ellenhorn JD, Cullinane CA, et al. Pazdur R, Coia L, R, Hoskins WJ, Wagman LD, Lawrence Kansas, CMP Medica LLC [Accessed May 8, 2011];Colon, rectal and anal cancers. Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2007 http://www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management/colorectal/article/10165/1802621.3.

Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, et al. The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:65–71. [PubMed]4.

Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. [PubMed]5.

Petrelli N, Douglass HO, Jr, Herrera L, et al. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group The modulation of fluorouracil with leucovorin in metastatic colorectal carcinoma: a prospective randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1419–1426. [PubMed]6.

Poon MA, O’Connell MJ, Wieand HS, et al. Biochemical modulation of fluorouracil with leucovorin: confirmatory evidence of improved therapeutic efficacy in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1967–1972. [PubMed]7.

Rabeneck L, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, et al. Outcomes of colorectal cancer in the United States: no change in survival (1986-1997) Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:471–477. [PubMed]8.

Scheithauer W, Rosen H, Kornek GV, et al. Randomised comparison of combination chemotherapy plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMJ. 1993;306:752–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed]9.

de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938–2947. [PubMed]10.

Douillard JY, Cunningham D, Roth AD, et al. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1041–1047. [PubMed]11.

Giacchetti S, Perpoint B, Zidani R, et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of oxaliplatin added to chrono-modulated fluorouracil-leucovorin as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:136–147. [PubMed]12.

Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, et al. Irinotecan Study Group Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:905–914. [PubMed]13.

Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. [PubMed]14.

Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. A randomized controlled trial of fluorouracil plus leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin combinations in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:23–30. [PubMed]15.

Tournigand C, Andre T, Achille E, et al. FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX6 or the reverse sequence in advanced colorectal cancer: a randomized GERCOR study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:229–237. [PubMed]16.

Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2696–2704. [PubMed]17.

Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–345. [PubMed]18.

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. [PubMed]19.

Mok TS, Yeo W, Johnson PJ, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study of Chinese herbal medicine as complementary therapy for reduction of chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:768–774. [PubMed]20.

Meng ZQ, Xu YY, Liu LM, et al. Clinical evaluation of integration of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and traditional Chinese medicine in treating metastatic liver cancer [in Chinese] Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2003;1:187–188. 233. [PubMed]21.

Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291:2720–2726. [PubMed]22.

Smith CA, Coyle ME. Recruitment and implementation strategies in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture and herbal medicine in women’s health. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14:81–86. [PubMed]23.

Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, et al. Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:477–485. [PubMed]24.

Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M, Given BA, et al. Predictors of use of complementary and alternative therapies among patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1115–1122. [PubMed]25.

Lawsin C, DuHamel K, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Demographic, medical, and psychosocial correlates to CAM use among survivors of colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:557–564. [PubMed]26.

West SG, Duan N, Pequegnat W, et al. Alternatives to the randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1359–1366. [PMC free article] [PubMed]27. Hernan MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the joint causal effect of nonrandomized treatments. J Am Stat Assoc. 2001;96:440–448.

28.

Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–788. [PubMed]29.

Mortimer KM, Neugebauer R, van der Laan M, et al. An application of model-fitting procedures for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:382–388. [PubMed]30.

Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. [PubMed]31. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

32. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc. 1984;79:516–524.

33.

Sato T, Matsuyama Y. Marginal structural models as a tool for standardization. Epidemiology. 2003;14:680–686. [PubMed]34.

Cole SR, Hernan MA, Margolick JB, et al. Marginal structural models for estimating the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation on CD4 cell count. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:471–478. [PubMed]35.

Petersen ML, Wang Y, van der Laan MJ, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of antiretroviral adherence interventions: using marginal structural models to replicate the findings of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(suppl 1):S96–S103. [PubMed]36.

Delaney JA, Daskalopoulou SS, Suissa S. Traditional versus marginal structural models to estimate the effectiveness of beta-blocker use on mortality after myocardial infarction. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2000;18:1–6. [PubMed]37.

Yamaguchi T, Ohashi Y. Adjusting for differential proportions of second-line treatment in cancer clinical trials. Part I: structural nested models and marginal structural models to test and estimate treatment arm effects. Stat Med. 2004;23:1991–2003. [PubMed]38.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297. [PMC free article] [PubMed]39.

Newell DJ. Intention-to-treat analysis: implications for quantitative and qualitative research. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:837–841. [PubMed]40.

O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on cancer sixth edition staging. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1420–1425. [PubMed]41.

Cappell MS. Reducing the incidence and mortality of colon cancer: mass screening and colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:129–160. vii-viii. [PubMed]42. American Joint Committee on Cancer, American Cancer Society, American College of Surgeons . AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 1997.

43. National Cancer Institute . SEER Program: Comparative Staging Guide for Cancer. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1993.

44. Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1972;34:187–220.

45. Efron B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat. 1979;7:1–26.

46. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat. 1985;39:33–38.

47.

Joffe MM, Rosenbaum PR. Invited commentary: propensity scores. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:327–333. [PubMed]48.

Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8, pt 2):757–763. [PubMed]49. Becker SO, Ichino A. Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. Stata J. 2002;2:358–377.

50.

O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, et al. Do young colon cancer patients have worse outcomes. World J Surg. 2004;28:558–562. [PubMed]51.

Lefebvre G, Delaney JA, Platt RW. Impact of mis-specification of the treatment model on estimates from a marginal structural model. Stat Med. 2008;27:3629–3642. [PubMed]52.

Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:656–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed]53.

Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer: a descriptive study. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:39. [PMC free article] [PubMed]54.

Dejardin O, Bouvier AM, Faivre J, et al. Access to care, socioeconomic deprivation and colon cancer survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:940–949. [PubMed]55.

Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:660–669. [PubMed]56.

Du XL, Meyer TE, Franzini L. Meta-analysis of racial disparities in survival in association with socioeconomic status among men and women with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:2161–2170. [PubMed]57.

Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Gray L, et al. Cigarette smoking and site-specific cancer mortality: testing uncertain associations using extended follow-up of the original Whitehall study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:996–1002. [PubMed]58.

Chao A, Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer mortality in the cancer prevention study II. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1888–1896. [PubMed]59.

Colangelo LA, Gapstur SM, Gann PH, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal carcinoma mortality in a cohort with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2004;100:288–293. [PubMed]60.

Botteri E, Iodice S, Raimondi S, et al. Cigarette smoking and adenomatous polyps: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:388–395. [PubMed]61.

Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298:754–764. [PubMed]62.

Ananda S, Field KM, Kosmider S, et al. Patient age and comorbidity are major determinants of adjuvant chemotherapy use for stage III colon cancer in routine clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4516–4517. author reply 4517-4518. [PubMed]63.

Macpherson H. Pragmatic clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:136–140. [PubMed]64.

Meta-Analysis Group In Cancer Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3537–3541. [PubMed]65.

Lo Bello L, Pistone G, Restuccia S, et al. 5-Fluorouracil alone versus 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid in the treatment of colorectal carcinoma: meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;38:553–562. [PubMed]66.

Sloan JA, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, et al. Women experience greater toxicity with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1491–1498. [PubMed]67.

Xiang D, Wang D, He Y, et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester induces growth arrest and apoptosis of colon cancer cells via the beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:753–762. [PubMed]68.

Russo A, Cardile V, Sanchez F, et al. Chilean propolis: antioxidant activity and antiproliferative action in human tumor cell lines. Life Sci. 2004;76:545–558. [PubMed]69.

Shimizu K, Das SK, Hashimoto T, et al. Artepillin C in Brazilian propolis induces G(0)/G(1) arrest via stimulation of Cip1/p21 expression in human colon cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2005;44:293–299. [PubMed]70.

Liao HF, Chen YY, Liu JJ, et al. Inhibitory effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and metastasis. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:7907–7912. [PubMed]71.

Majumdar AP, Kodali U, Jaszewski R. Chemopreventive role of folic acid in colorectal cancer. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2725–2732. [PubMed]72.

Strohle A, Wolters M, Hahn A. Folic acid and colorectal cancer prevention: molecular mechanisms and epidemiological evidence (Review) Int J Oncol. 2005;26:1449–1464. [PubMed]73.

Estensen RD, Levy M, Klopp SJ, et al. N-acetylcysteine suppression of the proliferative index in the colon of patients with previous adenomatous colonic polyps. Cancer Lett. 1999;147:109–114. [PubMed]74.

Sakano K, Takahashi M, Kitano M, et al. Suppression of azoxymethane-induced colonic premalignant lesion formation by coenzyme Q10 in rats. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:599–603. [PubMed]75.

Du B, Jiang L, Xia Q, et al. Synergistic inhibitory effects of curcumin and 5-fluorouracil on the growth of the human colon cancer cell line HT-29. Chemotherapy. 2006;52:23–28. [PubMed]76.

Patel BB, Sengupta R, Qazi S, et al. Curcumin enhances the effects of 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in mediating growth inhibition of colon cancer cells by modulating EGFR and IGF-1R. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:267–273. [PubMed]77.

Su CC, Lin JG, Li TM, et al. Curcumin-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer colo 205 cells through the production of ROS, Ca2+ and the activation of caspase-3. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:4379–4389. [PubMed]78.

Johnson JJ, Mukhtar H. Curcumin for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;255:170–181. [PubMed]79.

Fish-oil supplementation reduces intestinal hyperproliferation in persons at risk for colon cancer. Nutr Rev. 1993;51:241–243. [PubMed]80.

Lindner MA. A fish oil diet inhibits colon cancer in mice. Nutr Cancer. 1991;15:1–11. [PubMed]81.

Coleman LJ, Landstrom EK, Royle PJ, et al. A diet containing alpha-cellulose and fish oil reduces aberrant crypt foci formation and modulates other possible markers for colon cancer risk in azoxymethane-treated rats. J Nutr. 2002;132:2312–2318. [PubMed]82.

Zhou GD, Popovic N, Lupton JR, et al. Tissue-specific attenuation of endogenous DNA I-compounds in rats by carcinogen azoxymethane: possible role of dietary fish oil in colon cancer prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1230–1235. [PubMed]83.

Parodi PW. A role for milk proteins and their peptides in cancer prevention. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:813–828. [PubMed]84.

Bargahi A, Rabbani-Chadegani A. Angiogenic inhibitor protein fractions derived from shark cartilage. Biosci Rep. 2008;28:15–21. [PubMed]85.

Miller DR, Anderson GT, Stark JJ, et al. Phase I/II trial of the safety and efficacy of shark cartilage in the treatment of advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3649–3655. [PubMed]86.

Hong KJ, Dunn DM, Shen CL, et al. Effects of Ganoderma lucidum on apoptotic and anti-inflammatory function in HT-29 human colonic carcinoma cells. Phytother Res. 2004;18:768–770. [PubMed]87.

Lu H, Kyo E, Uesaka T, et al. A water-soluble extract from cultured medium of Ganoderma lucidum (Rei-shi) mycelia suppresses azoxymethane-induction of colon cancers in male F344 rats. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:375–379. [PubMed]88.

Lu H, Kyo E, Uesaka T, et al. Prevention of development of N,N’-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon tumors by a water-soluble extract from cultured medium of Ganoderma lucidum (Rei-shi) mycelia in male ICR mice. Int J Mol Med. 2002;9:113–117. [PubMed]89.

Lu H, Uesaka T, Katoh O, et al. Prevention of the development of preneoplastic lesions, aberrant crypt foci, by a water-soluble extract from cultured medium of Ganoderma lucidum (Rei-shi) mycelia in male F344 rats. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:1341–1345. [PubMed]90.

Lee MY, Lin HY, Cheng F, et al. Isolation and characterization of new lactam compounds that inhibit lung and colon cancer cells from adlay (Coix lachryma-jobi L. var. mayuen Stapf) bran. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1933–1939. [PubMed]91.

Hynes JB, Kumar A, Tomazic A, et al. Synthesis of 5-chloro-5,8-dideaza analogues of folic acid and aminopterin targeted for colon adenocarcinoma. J Med Chem. 1987;30:1515–1519. [PubMed]92.

Sugiyama T, Sadzuka Y. Theanine and glutamate transporter inhibitors enhance the antitumor efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1653:47–59. [PubMed]93.

Cerea G, Vaghi M, Ardizzoia A, et al. Biomodulation of cancer chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized study of weekly low-dose irinotecan alone versus irinotecan plus the oncostatic pineal hormone melatonin in metastatic colorectal cancer patients progressing on 5-fluorouracil-containing combinations. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:1951–1954. [PubMed]94.

Kakuda T. Neuroprotective effects of the green tea components theanine and catechins. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:1513–1518. [PubMed]95.

Nathan PJ, Lu K, Gray M, et al. The neuropharmacology of L-theanine(N-ethyl-l-glutamine): a possible neuroprotective and cognitive enhancing agent. J Herb Pharmacother. 2006;6:21–30. [PubMed]96.

Ioannides C, Hall DE, Mulder DE, et al. A comparison of the protective effects of N-acetyl-cysteine and S-carboxymethylcysteine against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 1983;28:313–321. [PubMed]97.

Sprague CL, Elfarra AA. Protection of rats against 3-butene-1, 2-diol-induced hepatotoxicity and hypoglycemia by N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:266–274. [PubMed]98.

Varma PS, Aruna K, Rukkumani R, et al. Alcohol and thermally oxidized PUFA induced oxidative stress: role of N-acetyl cysteine. Ital J Biochem. 2004;53:10–15. [PubMed]99.

Berend N. Inhibition of bleomycin lung toxicity by N-acetyl cysteine in the rat. Pathology. 1985;17:108–110. [PubMed]100.

Gon Y, Hashimoto S, Nakayama T, et al. N-acetyl-l-cysteine inhibits bleomycin-induced interleukin-8 secretion by bronchial epithelial cells. Respirology. 2000;5:309–313. [PubMed]101.

Trizna Z, Schantz SP, Hsu TC. Effects of N-acetyl-l-cysteine and ascorbic acid on mutagen-induced chromosomal sensitivity in patients with head and neck cancers. Am J Surg. 1991;162:294–298. [PubMed]102.

Takimoto M, Sakurai T, Kodama K, et al. Protective effect of CoQ 10 administration on cardial toxicity in FAC therapy [in Japanese] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1982;9:116–121. [PubMed]103.

Okada K, Yamada S, Kawashima Y, et al. Cell injury by anti-neoplastic agents and influence of coenzyme Q10 on cellular potassium activity and potential difference across the membrane in rat liver cells. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1663–1667. [PubMed]104.

Osterlund P, Ruotsalainen T, Korpela R, et al. Lactobacillus supplementation for diarrhoea related to chemotherapy of colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1028–1034. [PMC free article] [PubMed]105.

Kim SH, Lee HJ, Kim JS, et al. Protective effect of an herbal preparation (HemoHIM) on radiation-induced intestinal injury in mice. J Med Food. 2009;12:1353–1358. [PubMed]106.

Jagetia GC. Radioprotective potential of plants and herbs against the effects of ionizing radiation. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2007;40:74–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed]107.

Takeda T, Kamiura S, Kimura T. Effectiveness of the herbal medicine daikenchuto for radiation-induced enteritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:753–755. [PubMed]108.

Tian YP, Wang QC. Rectal radiation injuries treated by Shen Ling Bai Zhu powders combined with rectal administration of western drugs [in Chinese] Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2008;28:159–160. [PubMed]109.

Sener G, Jahovic N, Tosun O, et al. Melatonin ameliorates ionizing radiation-induced oxidative organ damage in rats. Life Sci. 2003;74:563–572. [PubMed]110.

Bincoletto C, Eberlin S, Figueiredo CA, et al. Effects produced by royal jelly on haematopoiesis: relation with host resistance against Ehrlich ascites tumour challenge. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:679–688. [PubMed]111.

Salazar-Olivo LA, Paz-Gonzalez V. Screening of biological activities present in honeybee (Apis mellifera) royal jelly. Toxicol In Vitro. 2005;19:645–651. [PubMed]112.

Beardsley TR, Pierschbacher M, Wetzel GD, et al. Induction of T-cell maturation by a cloned line of thymic epithelium (TEPI) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:6005–6009. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

TCM, Chinese kruiden, Yoga, acupunctuur, voeding, voedingsuppletie, vitamines, Qi-Gong, Tai Ji, beweging, Houtsmullerdieet, Moermandieet, Gersondieet, darmkanker, uitgezaaide darmkanker

Gerelateerde artikelen

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Aanvullende niet toxische ondersteuning met bv. dieet, Chinese kruiden, acupunctuur, yoga enz. naast reguliere behandelingen bij darmkanker, vermindert kans op overlijden met 26 procent op 5 jaar. copy 1"