Mocht u kanker-actueel de moeite waard vinden en ons willen ondersteunen om kanker-actueel online te houden dan kunt u ons machtigen voor een periodieke donatie via donaties: https://kanker-actueel.nl/NL/donaties.html of doneer al of niet anoniem op - rekeningnummer NL79 RABO 0372931138 t.n.v. Stichting Gezondheid Actueel in Amersfoort. Onze IBANcode is NL79 RABO 0372 9311 38

Elk bedrag is welkom. En we zijn een ANBI instelling dus uw donatie of gift is in principe aftrekbaar voor de belasting.

En als donateur kunt u ook korting krijgen bij verschillende bedrijven:

https://kanker-actueel.nl/NL/voordelen-van-ops-lidmaatschap-op-een-rijtje-gezet-inclusief-hoe-het-kookboek-en-de-recepten-op-basis-van-uitgangspunten-van-houtsmullerdieet-te-downloaden-enof-in-te-zien.html

19 december 2016: Bron: Front Nutr. 2016; 3: 24. Published online 2016 Aug 16.

Veel groenten hebben voedingsstoffen waarvan bekend is dat die anti kanker effecten hebben. Zo maken groenten als broccoli, spruitjes (algemeen aangeduid als kruisbloemige groenten) bijna altijd deel uit van een dieet ter voorkoming of bestrijding van kanker. En alle bekende dieëten adviseren dagelijks salades en soms zelfs rauwe groenten te eten.

In een studierapport Bioavailability of Glucosinolates and Their Breakdown Products: Impact of Processing beschrijven onderzoekers aan de hand van de literatuur de invloed van bewaren (in of buiten de koelkast bv.) en de manier van bereiden op de zogeheten biobeschikbaarheid (= opname mogelijkheid door het lichaam van die goede voedingsstoffen) die bepalend zijn voor de effectiviteit van voedingsstoffen in relatie tot preventie en / of bestrijding van kanker.

Bij de meeste groenten verliezen deze bij koken of bereiden via de magnetron ca. 60 procent van hun voedingswaarde tegenover ca. 10 tot 20 procent bij stomen of soms zelfs niets bij rauw eten. Maar verschilt ook per groente. En soms is het eten van iets anders erbij (vezels bv.) ook beter voor de opname beschikbaarheid. Raadpleeg dus altijd een gekwalificeerd voedingsdeskundige / natuurarts als u een bepaald dieet wilt gaan gebruiken.

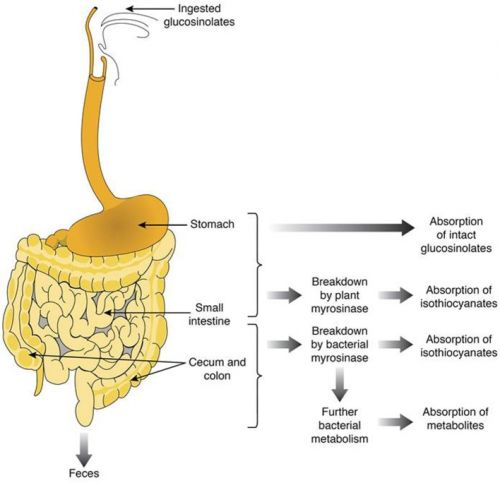

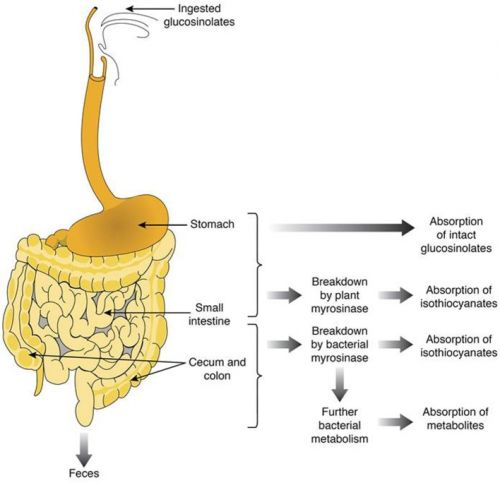

Tekst gaat verder onder foto, die een schematisch beeld geeft van waar en hoe bepaalde voedingsstoffen worden opgenomen of afgebroken door het lichaam

Bron foto: Frontiers in Nutrition

Het rapport is wel in medische taal maar duidelijk is wel dat stomen van groenten veel beter is dan koken of de magnetron. En dat rauw eten van sommige groenten (broccoli bv.) soms het beste is, maar niet altijd.

Hier een schema uit dat rapport dat volgens mij duidelijk genoeg is en hoef ik niet te vertalen neem ik aan:

Table 2

Impact of cooking conditions on glucosinolates and their breakdown products.

| Cooking conditions | Main findings | Reference |

|---|

| Boiling or steaming for 10 min |

Reducing sinigrin by 9.6 and 29.1% in steamed and boiled cauliflower |

(134) |

| Blanching, microwaving, or steaming cabbage for up to 10 min |

Blanching decreased glucosinolate and S-methylmethionine levels, whereas microwaving or steaming preserved them |

(135) |

| Steaming for 10 min, boiling for 15 min, and high-pressure cooking for 7 min |

Losses between 20–33% and 45–60% in pressure treatment and boiled vegetables, respectively. Breakdown products of aliphatic glucosinolates decreased from 5 to 12% in steamed, 18 to 23% in pressure-cooked, and 37 to 45% in boiled samples |

(136) |

| Boiling Brussels sprouts at 100°C for 5, 15, and 30 min |

The presence of seven breakdown products (indole-3-acetonitrile, indole-3-carbinol, ascorbigen, 3,3′-diindolylmethane, 3-butenylnitrile, 4-methylsulfinylbutanenitrile, and 2-phenylacetonitrile) after boiling |

(137) |

| Boiling for 5 min. Stir-frying at 130°C for 5 min. Microwaving (450 W) for 5 min. Steaming for 5 min |

Compared with fresh-cut red cabbage, all cooking methods were found to cause significant reduction in total glucosinolates contents |

(138) |

| Boiling in water with a cold start (25°C); boiling with a hot start (100°C); and steaming |

Steaming showed an increase in the amount of total glucosinolates (+17%). Boiling-hot start (−41%) and boiling-cold start (−50%) reduced total glucosinolates |

(139) |

| Cutting (2-inch pieces) and then hot water blanching at 66, 76, 86, and 96°C for 145 s |

Blanching at ≥86°C inactivated peroxidase, lipoxygenase, and myrosinase. Blanching at 76°C inactivated 92% of lipoxygenase activity, and leads to 18% loss in myrosinase-dependent sulforaphane formation |

(140) |

| Radio frequency cooking in oven transferring 180 kJ. Steaming for 8 min at 100°C |

Increasing glucosinolates from 10.4 μmol g−1 DW in fresh broccoli to 13.1 and 23.7 μmol g−1 DW after radio frequency cooking and steaming, respectively |

(141) |

| Cooking at 100°C for 8 and 12 min |

Limited thermal degradation of glucoraphanin (less than 12%) was observed when broccoli was placed in vacuum-sealed bag |

(142) |

| Cutting broccoli (15 cm long). Boiling for 3.5 min at 100°C. Low pressure (0.02 MPa) steaming at 100°C, 5 min. High-pressure (0.1 MPa) steaming for 2 min. Under vacuum treatment at 90°C for 15 min. Microwaving at 900 W, 2.5 min. Vacuum-microwaving (−98.2 kPa) at 900 W, 2.5 min |

Boiling and under vacuum processing induced the highest glucosinolate loss (80%), while low-pressure steaming, microwaving, and vacuum-microwaving showed the lowest (40%) loss |

(143) |

| Blanching broccoli for 30, 90, and 120 s. Stir-frying at 100–130°C for 90 s. Microwaving at 800 W for 90 s |

Blanching at 120 s decreased total glucosinolates by 36%, stir-frying and microwaving decreased them by 13–26% |

(144) |

| Boiling and steaming Portuguese cabbage for 12 min, and for 15 min for the other Brassica. Microwaving at 850 W, 8 min |

Steaming contributed to the higher glucosinolates preservation, whereas boiling water led to higher losses (57% in Brassica oleracea and 81% in Brassica rapa cultivars) |

(127) |

| Microwaving at 1100 W, steaming and boiling. Cooking times were 2 or 5 min |

Steaming resulted in higher retention of glucosinolates, while boiling and microwaving resulted in significant losses |

(145) |

| Boiling, high-pressure cooking, and steaming for up to 15 min |

Better preservation of glucosinolates with steaming. Similar losses (64%) after boiling and high-pressure cooking |

(146) |

| Microwaving (590 W, 5 min), frying (180°C, 5 min), frying (3 min)/microwaving (2 min), steaming (5 min), and baking (200°C, 5 min) |

Significant modifications of total aliphatic and indole glucosinolates by all cooking treatments, except for steaming |

(147) |

Een ander studierapport onderzocht de invloed van kruisbloemige groenten bij darmkanker.

Ook uit dit rapport blijkt dat het opslaan en vooral de bereiding van die groenten een grote rol speelt in het wel of geen effectiviteit in relatie tot darmkanker. Zie dit studierapport in PDF formaat: Cruciferous vegetables and colo-rectal cancer

Het abstract van die laatste studie staat hieronder met interessante referentielijst met doorklikbare andere studies gerelateerd aan dit onderwerp.

When cruciferous are cooked before consumption, myrosinase is inactivated and glucosinolates transit to the colon where they are hydrolyzed by the intestinal microbiota. Numerous factors, such as storage time, temperature, and atmosphere packaging, along with inactivation processes of myrosinase are influencing the bioavailability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products.

Bioavailability of Glucosinolates and Their Breakdown Products: Impact of Processing

Abstract

Glucosinolates are a large group of plant secondary metabolites with nutritional effects, and are mainly found in cruciferous plants. After ingestion, glucosinolates could be partially absorbed in their intact form through the gastrointestinal mucosa. However, the largest fraction is metabolized in the gut lumen. When cruciferous are consumed without processing, myrosinase enzyme present in these plants hydrolyzes the glucosinolates in the proximal part of the gastrointestinal tract to various metabolites, such as isothiocyanates, nitriles, oxazolidine-2-thiones, and indole-3-carbinols. When cruciferous are cooked before consumption, myrosinase is inactivated and glucosinolates transit to the colon where they are hydrolyzed by the intestinal microbiota. Numerous factors, such as storage time, temperature, and atmosphere packaging, along with inactivation processes of myrosinase are influencing the bioavailability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products. This review paper summarizes the assimilation, absorption, and elimination of these molecules, as well as the impact of processing on their bioavailability.

Conclusion

Bioavailability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products depends on many factors, including the inactivation or not of myrosinase, the processing and storage conditions, and the association with other food constituents. It is well known that consumption of Brassica vegetables is associated with anticarcinogenic effects and other beneficial biological activities of the breakdown products. Numerous studies have described the assimilation and metabolism of both glucosinolates and their derivatives, however, the literature is lacking the description of detailed mechanisms and models associated with these phenomena. With regard to the beneficial effects of glucosinolates, in addition to breeding, transgenic plants could also be a possible way to enhance specific molecules by either overexpressing or inactivating genes, or even more, cloning regulatory factors, which is insufficiently studied up to the present.

Author Contributions

FB, NN, SR, AK, ZZ, and MK have been involved in checking literature, writing the paper, and reviewing the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

FB was supported from the Union by a postdoctoral Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship (Marie Curie IEF) within the 7th European Community Framework Programme (http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/mariecurieactions/ief_en.html) (project number 626524 – HPBIOACTIVE – Mechanistic modeling of the formation of bioactive compounds in high pressure processed seedlings of Brussels sprouts for effective solution to preserve healthy compounds in vegetables).

Abbreviations

ESP, epithiospecifier protein; ITCs, isothiocyanates; MAP: modified atmosphere packaging; NAC, N-acetyl-l-cysteine.

References

1.

Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P.. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry (2001) 56:5–51.10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00316-2 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]2.

Agerbirk N, Olsen CE. Glucosinolate structures in evolution. Phytochemistry (2012) 77:16–45.10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.02.005 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]3.

Franco P, Spinozzi S, Pagnotta E, Lazzeri L, Ugolini L, Camborata C, et al. Development of a liquid chromatography – electrospray ionization – tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous analysis of intact glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in Brassicaceae seeds and functional foods. J Chromatogr A (2016) 1428:154–61.10.1016/j.chroma.2015.09.001 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]4.

Deng Q, Zinoviadou KG, Galanakis CM, Orlien V, Grimi N, Vorobiev E, et al. The effects of conventional and non-conventional processing on glucosinolates and its derived forms, isothiocyanates: extraction, degradation, and applications. Food Eng Rev (2014) 7:357–81.10.1007/s12393-014-9104-9 [Cross Ref]5. Amiot-Carlin MJ, Coxam V, Strigler F. Les phytomicronutriments. Paris: Tec & doc; (2012).

6.

Halkier BA, Gershenzon J.. Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu Rev Plant Biol (2006) 57:303–33.10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105228 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]7.

Williams DJ, Critchley C, Pun S, Chaliha M, O’Hare TJ.. Differing mechanisms of simple nitrile formation on glucosinolate degradation in Lepidium sativum and Nasturtium officinale seeds. Phytochemistry (2009) 70:1401–9.10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.07.035 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]8.

Lee M-K, Chun J-H, Byeon DH, Chung S-O, Park SU, Park S, et al. Variation of glucosinolates in 62 varieties of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) and their antioxidant activity. LWT – Food Sci Technol (2014) 58:93–101.10.1016/j.lwt.2014.03.001 [Cross Ref]9.

Grubb CD, Abel S.. Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci (2006) 11:89–100.10.1016/j.tplants.2005.12.006 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]10.

Holst B, Williamson G.. A critical review of the bioavailability of glucosinolates and related compounds. Nat Prod Rep (2004) 21:425–47.10.1039/b204039p [PubMed] [Cross Ref]11.

Munday R, Munday CM.. Induction of phase II detoxification enzymes in rats by plant-derived isothiocyanates: comparison of allyl isothiocyanate with sulforaphane and related compounds. J Agric Food Chem (2004) 52:1867–71.10.1021/jf030549s [PubMed] [Cross Ref]12.

Munday R, Munday CM.. Selective induction of phase II enzymes in the urinary bladder of rats by allyl isothiocyanate, a compound derived from Brassica vegetables. Nutr Cancer (2002) 44:52–9.10.1207/S15327914NC441_7 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]13.

Geng F, Tang L, Li Y, Yang L, Choi K-S, Kazim AL, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate arrests cancer cells in mitosis, and mitotic arrest in turn leads to apoptosis via Bcl-2 protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:32259–67.10.1074/jbc.M111.278127 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]14.

Smith TK, Lund EK, Parker ML, Clarke RG, Johnson IT.. Allyl-isothiocyanate causes mitotic block, loss of cell adhesion and disrupted cytoskeletal structure in HT29 cells. Carcinogenesis (2004) 25:1409–15.10.1093/carcin/bgh149 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]15.

Pham N-A, Jacobberger JW, Schimmer AD, Cao P, Gronda M, Hedley DW.. The dietary isothiocyanate sulforaphane targets pathways of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and oxidative stress in human pancreatic cancer cells and inhibits tumor growth in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Mol Cancer Ther (2004) 3:1239–48. [PubMed]16.

Guerrero-Díaz MM, Lacasa-Martínez CM, Hernández-Piñera A, Martínez-Alarcón V, Lacasa-Plasencia A. Evaluation of repeated biodisinfestation using Brassica carinata pellets to control Meloidogyne incognita in protected pepper crops. Span J Agric Res (2013) 11:485–93.10.5424/sjar/2013112-3275 [Cross Ref]17.

Sarwar M, Kirkegaard JA, Wong PTW, Desmarchelier JM. Biofumigation potential of brassicas. Plant Soil (1998) 201:103–12.10.1023/A:1004381129991 [Cross Ref]18.

Sotelo T, Lema M, Soengas P, Cartea ME, Velasco P.. In vitro activity of glucosinolates and their degradation products against brassica-pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol (2015) 81:432–40.10.1128/AEM.03142-14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]19.

Hooker WJ, Walker JC, Smith FG. Toxicity of beta-phenethyl isothiocyanate to certain fungi. Am J Bot (1943) 30:632–7.10.2307/2437478 [Cross Ref]20.

Mayton HS, Oliver C, Vaughn SF, Loria R. Correlation of fungicidal activity of Brassica species with allyl isothiocyanate production in macerated leaf tissue. Phytopathology (1996) 86:267–71.10.1094/Phyto-86-267 [Cross Ref]21.

Smolinska U, Horbowicz M. Fungicidal activity of volatiles from selected cruciferous plants against resting propagules of soil-borne fungal pathogens. J Phytopathol (1999) 147:119–24.10.1111/j.1439-0434.1999.tb03817.x [Cross Ref]22.

Sarwar M, Kirkegaard JA, Wong PTW, Desmarchelier JM. Biofumigation potential of brassicas: III. In vitro toxicity of isothiocyanates to soil-borne fungal pathogens. Plant Soil (1998) 201:103–12.10.1023/A:1004381129991 [Cross Ref]23.

Chung WC, Huang JW, Huang HC, Jen JF. Control, by Brassica seed pomace combined with Pseudomonas boreopolis, of damping-off of watermelon caused by Pythium sp. Can J Plant Pathol (2003) 25:285–94.10.1080/07060660309507081 [Cross Ref]24.

Manyes L, Luciano FB, Mañes J, Meca G. In vitro antifungal activity of allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) against Aspergillus parasiticus and Penicillium expansum and evaluation of the AITC estimated daily intake. Food Chem Toxicol (2015) 83:293–9.10.1016/j.fct.2015.06.011 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]25.

Smolinska U, Morra MJ, Knudsen GR, James RL. Isothiocyanates produced by Brassicaceae species as inhibitors of Fusarium oxysporum. Plant Dis (2003) 87:407–12.10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.4.407 [Cross Ref]26.

Drobnica Ľ, Zemanová M, Nemec P, Antoš K, Kristián P, Štullerová A, et al. Antifungal activity of isothiocyanates and related compounds. I. Naturally occurring isothiocyanates and their analogues. Appl Microbiol (1967) 15:701–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]27.

Mari M, Iori R, Leoni O, Marchi A. In vitro activity of glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates against postharvest fruit pathogens. Ann Appl Biol (1993) 123:155–64.10.1111/j.1744-7348.1993.tb04082.x [Cross Ref]28.

Manici LM, Lazzeri L, Palmieri S. In vitro fungitoxic activity of some glucosinolates and their enzyme-derived products toward plant pathogenic fungi. J Agric Food Chem (1997) 45:2768–73.10.1021/jf9608635 [Cross Ref]29.

Manici LM, Lazzeri L, Baruzzi G, Leoni O, Galletti S, Palmieri S. Suppressive activity of some glucosinolate enzyme degradation products on Pythium irregulare and Rhizoctonia solani in sterile soil. Pest Manag Sci (2000) 56:921–6.10.1002/1526-4998(200010)56:10<921::AID-PS232>3.3.CO;2-C [Cross Ref]30.

Smissman EE, Beck SD, Boots MR.. Growth inhibition of insects and a fungus by indole-3-acetonitrile. Science (1961) 133:462.10.1126/science.133.3451.462 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]31.

Lewis JA, Papavizas GC. Effect of sulphur-containing volatile compounds and vapors from cabbage decomposition on Aphanomyces euteiches. Phytopathology (1971) 61:208–14.10.1094/Phyto-61-208 [Cross Ref]32.

Mithen RF, Lewis BG, Fenwick GR. In vitro activity of glucosinolates and their products against Leptosphaeria maculans. Trans Br Mycol Soc (1986) 87:433–40.10.1016/S0007-1536(86)80219-4 [Cross Ref]33.

Schreiner RP, Koide RT. Antifungal compounds from the roots of mycotrophic and non-mycotrophic plant species. New Phytol (1993) 123:99–105.10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb04535.x [Cross Ref]34.

Sexton AC, Kirkegaard JA, Howlett BJ. Glucosinolates in Brassica juncea and resistance to Australian isolates of Leptosphaeria maculans, the blackleg fungus. Australas Plant Pathol (1999) 28:95–102.10.1071/AP99017 [Cross Ref]35.

Dawson GW, Doughty KJ, Hick AJ, Pickett JA, Pye BJ, Smart LE, et al. Chemical precursors for studying the effects of glucosinolate catabolites on diseases and pests of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) or related plants. Pestic Sci (1993) 39:271–8.10.1002/ps.2780390404 [Cross Ref]36.

Angus JF, Gardner PA, Kirkegaard JA, Desmarchelier JM. Biofumigation: isothiocyanates released from brassica roots inhibit growth of the take-all fungus. Plant Soil (1994) 162:107–12.10.1007/BF01416095 [Cross Ref]37.

Fenwick GR, Heaney RK, Mullin WJ. Glucosinolates and their breakdown products in food and food plants. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr (1983) 18:123–201.10.1080/10408398209527361 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]38.

Sanchi S, Odorizzi S, Lazzeri L, Marciano P. Effect of Brassica carinata seed meal treatment on the Trichoderma harzianum t39–Sclerotinia species interaction. Acta Hortic (2005) 698:287–92.10.17660/ActaHortic.2005.698.38 [Cross Ref]39.

Smolinska U, Knudsen GR, Morra MJ, Borek V. Inhibition of Aphanomyces euteiches f. sp. pisi by volatiles produced by hydrolysis of Brassica napus seed meal. Plant Dis (1997) 81:288–92.10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.3.288 [Cross Ref]40.

Isshiki K, Tokuoka K, Mori R, Chiba S. Preliminary examination of allyl isothiocyanate vapor for food preservation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem (1992) 56:1476–7.10.1271/bbb.56.1476 [Cross Ref]41. Delaquis PJ, Sholberg PL. Antimicrobial activity of gaseous allyl isothiocyanate. J Food Prot (1997) 60:943–7.

42.

Lin CM, Kim J, Du WX, Wei CI.. Bactericidal activity of isothiocyanate against pathogens on fresh produce. J Food Prot (2000) 63:25–30. [PubMed]43.

Park CM, Taormina PJ, Beuchat LR.. Efficacy of allyl isothiocyanate in killing enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 on alfalfa seeds. Int J Food Microbiol (2000) 56:13–20.10.1016/S0168-1605(99)00202-0 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]44.

Nadarajah D, Han JH, Holley RA.. Use of mustard flour to inactivate Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ground beef under nitrogen flushed packaging. Int J Food Microbiol (2005) 99:257–67.10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.08.018 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]45.

Dias C, Aires A, Saavedra MJ. Antimicrobial activity of isothiocyanates from cruciferous plants against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int J Mol Sci (2014) 15:19552–61.10.3390/ijms151119552 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]46. Ekanayake A, Kester JJ, Li JJ, Zehentbauer GN, Bunke PR, Zent JB. Isogard(tm) a natural anti-microbial agent derived from white mustard seed. International Symposium on Natural Preservatives in Food Systems No1. Princeton, USA: International Society for Horticultural Science, 709, p. 101–8.

47.

Monu EA, David JRD, Schmidt M, Davidson PM.. Effect of white mustard essential oil on the growth of foodborne pathogens and spoilage microorganisms and the effect of food components on its efficacy. J Food Prot (2014) 77:2062–8.10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-257 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]48.

Fahey JW, Haristoy X, Dolan PM, Kensler TW, Scholtus I, Stephenson KK, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99:7610–5.10.1073/pnas.112203099 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]49.

Haristoy X, Angioi-Duprez K, Duprez A, Lozniewski A. Efficacy of sulforaphane in eradicating Helicobacter pylori human gastric xenografts implanted in nude mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2003) 47:3982–4.10.1128/AAC.47.12.3982-3984.2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]50.

Haristoy X, Fahey JW, Scholtus I, Lozniewski A.. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effects of several isothiocyanates on Helicobacter pylori. Planta Med (2005) 71:326–30.10.1055/s-2005-864098 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]51.

Bending GD, Lincoln SD. Inhibition of soil nitrifying bacteria communities and their activities by glucosinolate hydrolysis products. Soil Biol Biochem (2000) 32:1261–9.10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00043-2 [Cross Ref]52.

Rutkowski A, Bielecka M, Kornacka D, Kozlowska H, Roczniakowa B. Rapeseed meal XX. Influence of toxic compounds of rapeseed meal on the technological properties of propionic acid bacteria. Can Inst Food Sci Technol J (1972) 5:67–71.10.1016/S0315-5463(72)74090-0 [Cross Ref]53. Schnug E, Ceynowa J. Phytopathological aspects of glucosinolates in oilseed rape. J Agron Crop Sci (1990) 165:319–28.

54.

Xu K, Thornalley PJ.. Studies on the mechanism of the inhibition of human leukaemia cell growth by dietary isothiocyanates and their cysteine adducts in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol (2000) 60:221–31.10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00319-1 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]55.

Srivastava SK, Xiao D, Lew KL, Hershberger P, Kokkinakis DM, Johnson CS, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate, a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits growth of PC-3 human prostate cancer xenografts in vivo. Carcinogenesis (2003) 24:1665–70.10.1093/carcin/bgg123 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]56.

Xiao D, Srivastava SK, Lew KL, Zeng Y, Hershberger P, Johnson CS, et al. Allyl isothiocyanate, a constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells by causing G2/M arrest and inducing apoptosis. Carcinogenesis (2003) 24:891–7.10.1093/carcin/bgg023 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]57.

Manesh C, Kuttan G.. Effect of naturally occurring isothiocyanates in the inhibition of cyclophosphamide-induced urotoxicity. Phytomedicine (2005) 12:487–93.10.1016/j.phymed.2003.04.005 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]58.

Sávio ALV, da S, Salvadori DMF.. Inhibition of bladder cancer cell proliferation by allyl isothiocyanate (mustard essential oil). Mutat Res (2015) 771:29–35.10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.11.004 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]59.

Rajakumar T, Pugalendhi P, Thilagavathi S.. Dose response chemopreventive potential of allyl isothiocyanate against 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced mammary carcinogenesis in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Chem Biol Interact (2015) 231:35–43.10.1016/j.cbi.2015.02.015 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]60.

Lui VWY, Wentzel AL, Xiao D, Lew KL, Singh SV, Grandis JR.. Requirement of a carbon spacer in benzyl isothiocyanate-mediated cytotoxicity and MAPK activation in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis (2003) 24:1705–12.10.1093/carcin/bgg127 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]61.

Srivastava SK, Singh SV.. Cell cycle arrest, apoptosis induction and inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B activation in anti-proliferative activity of benzyl isothiocyanate against human pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis (2004) 25:1701–9.10.1093/carcin/bgh179 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]62.

Kuroiwa Y, Nishikawa A, Kitamura Y, Kanki K, Ishii Y, Umemura T, et al. Protective effects of benzyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane but not resveratrol against initiation of pancreatic carcinogenesis in hamsters. Cancer Lett (2006) 241:275–80.10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.028 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]63.

Zhu Y, Liu A, Zhang X, Qi L, Zhang L, Xue J, et al. The effect of benzyl isothiocyanate and its computer-aided design derivants targeting alkylglycerone phosphate synthase on the inhibition of human glioma U87MG cell line. Tumor Biol (2015) 36:3499–509.10.1007/s13277-014-2986-6 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]64.

Abe N, Hou D-X, Munemasa S, Murata Y, Nakamura Y.. Nuclear factor-kappaB sensitizes to benzyl isothiocyanate-induced antiproliferation in p53-deficient colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis (2014) 5:e1534.10.1038/cddis.2014.495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]65.

Cover CM, Hsieh SJ, Cram EJ, Hong C, Riby JE, Bjeldanes LF, et al. Indole-3-carbinol and tamoxifen cooperate to arrest the cell cycle of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res (1999) 59:1244–51. [PubMed]66.

Singh RK, Lange TS, Kim K, Zou Y, Lieb C, Sholler GL, et al. Effect of indole ethyl isothiocyanates on proliferation, apoptosis, and MAPK signaling in neuroblastoma cell lines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett (2007) 17:5846–52.10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.08.032 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]67.

Rose P, Huang Q, Ong CN, Whiteman M.. Broccoli and watercress suppress matrix metalloproteinase-9 activity and invasiveness of human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol (2005) 209:105–13.10.1016/j.taap.2005.04.010 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]68.

Gamet-Payrastre L, Li P, Lumeau S, Cassar G, Dupont MA, Chevolleau S, et al. Sulforaphane, a naturally occurring isothiocyanate, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HT29 human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res (2000) 60:1426–33. [PubMed]69.

Singletary K, MacDonald C.. Inhibition of benzo[a]pyrene- and 1,6-dinitropyrene-DNA adduct formation in human mammary epithelial cells bydibenzoylmethane and sulforaphane. Cancer Lett (2000) 155:47–54.10.1016/S0304-3835(00)00412-2 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]70.

Chung FL, Conaway CC, Rao CV, Reddy BS.. Chemoprevention of colonic aberrant crypt foci in Fischer rats by sulforaphane and phenethyl isothiocyanate. Carcinogenesis (2000) 21:2287–91.10.1093/carcin/21.12.2287 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]71.

Bonnesen C, Eggleston IM, Hayes JD.. Dietary indoles and isothiocyanates that are generated from cruciferous vegetables can both stimulate apoptosis and confer protection against DNA damage in human colon cell lines. Cancer Res (2001) 61:6120–30.10.3892/or.10.6.2045 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]72.

Fimognari C, Nüsse M, Cesari R, Iori R, Cantelli-Forti G, Hrelia P.. Growth inhibition, cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia by the isothiocyanate sulforaphane. Carcinogenesis (2002) 23:581–6.10.1093/carcin/23.4.581 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]73.

Misiewicz I, Skupinska K, Kasprzycka-Guttman T.. Sulforaphane and 2-oxohexyl isothiocyanate induce cell growth arrest and apoptosis in L-1210 leukemia and ME-18 melanoma cells. Oncol Rep (2003) 10:2045–50. [PubMed]74.

Kim B-R, Hu R, Keum Y-S, Hebbar V, Shen G, Nair SS, et al. Effects of glutathione on antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression and apoptosis elicited by sulforaphane. Cancer Res (2003) 63:7520–5. [PubMed]75.

Singh AV, Xiao D, Lew KL, Dhir R, Singh SV.. Sulforaphane induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in cultured PC-3 human prostate cancer cells and retards growth of PC-3 xenografts in vivo. Carcinogenesis (2004) 25:83–90.10.1093/carcin/bgg178 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]76.

Gingras D, Gendron M, Boivin D, Moghrabi A, Théorêt Y, Béliveau R.. Induction of medulloblastoma cell apoptosis by sulforaphane, a dietary anticarcinogen from Brassica vegetables. Cancer Lett (2004) 203:35–43.10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.025 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]77.

Wang L, Liu D, Ahmed T, Chung F-L, Conaway C, Chiao J-W.. Targeting cell cycle machinery as a molecular mechanism of sulforaphane in prostate cancer prevention. Int J Oncol (2004) 24:187–92.10.3892/ijo.24.1.187 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]78.

Morse MA, Wang CX, Stoner GD, Mandal S, Conran PB, Amin SG, et al. Inhibition of 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced DNA adduct formation and tumorigenicity in the lung of F344 rats by dietary phenethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Res (1989) 49:549–53. [PubMed]79.

Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho CG, Posner GH, Talalay P.. Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1994) 91:3147–50.10.1073/pnas.91.8.3147 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]80.

Chiao JW, Chung F, Krzeminski J, Amin S, Arshad R, Ahmed T, et al. Modulation of growth of human prostate cancer cells by the N-acetylcysteine conjugate of phenethyl isothiocyanate. Int J Oncol (2000) 16:1215–9. [PubMed]81.

Xiao D, Singh SV.. Phenethyl isothiocyanate-induced apoptosis in p53-deficient PC-3 human prostate cancer cell line is mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. Cancer Res (2002) 62:3615–9.10.3892/ijo.16.6.1215 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]82.

Chen Y-R, Han J, Kori R, Kong A-NT, Tan T-H.. Phenylethyl isothiocyanate induces apoptotic signaling via suppressing phosphatase activity against c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem (2002) 277:39334–42.10.1074/jbc.M202070200 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]83.

Nishikawa A, Morse MA, Chung F-L.. Inhibitory effects of 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate and 6-phenylhexyl isothiocyanate on urinary bladder tumorigenesis in rats induced by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine. Cancer Lett (2003) 193:11–6.10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00097-6 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]84.

Jeong W-S, Kim I-W, Hu R, Kong A-NT.. Modulatory properties of various natural chemopreventive agents on the activation of NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Pharm Res (2004) 21:661–70.10.1023/B:PHAM.0000022413.43212.cf [PubMed] [Cross Ref]85.

Johnson CR, Chun J, Bittman R, Jarvis WD.. Intrinsic cytotoxicity and chemomodulatory actions of novel phenethylisothiocyanate sphingoid base derivatives in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther (2004) 309:452–61.10.1124/jpet.103.060665 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]86.

Pullar JM, Thomson SJ, King MJ, Turnbull CI, Midwinter RG, Hampton MB.. The chemopreventive agent phenethyl isothiocyanate sensitizes cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Carcinogenesis (2004) 25:765–72.10.1093/carcin/bgh063 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]87.

Wu X, Kassie F, Mersch-Sundermann V.. Induction of apoptosis in tumor cells by naturally occurring sulfur-containing compounds. Mutat Res (2005) 589:81–102.10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.11.001 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]88.

Satyan KS, Swamy N, Dizon DS, Singh R, Granai CO, Brard L.. Phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) inhibits growth of ovarian cancer cells by inducing apoptosis: role of caspase and MAPK activation. Gynecol Oncol (2006) 103:261–70.10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.002 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]89.

Yu R, Mandlekar S, Harvey KJ, Ucker DS, Kong AN.. Chemopreventive isothiocyanates induce apoptosis and caspase-3-like protease activity. Cancer Res (1998) 58:402–8. [PubMed]90.

Heaney RP.. Factors influencing the measurement of bioavailability, taking calcium as a model. J Nutr (2001) 131:1344–8. [PubMed]91. Wood RJ. Bioavailability: definition, general aspects and fortificants. In: Caballero B, Prentice A, Allen L, editors. , editors, Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, 2nd ed Oxford: Elsevier Ltd; (2005).

92.

Mithen RF, Dekker M, Verkerk R, Rabot S, Johnson IT. The nutritional significance, biosynthesis and bioavailability of glucosinolates in human foods. J Sci Food Agric (2000) 80:967–84.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(20000515)80:7<967::AID-JSFA597>3.3.CO;2-M [Cross Ref]93.

Johnson IT.. Glucosinolates: bioavailability and importance to health. Int J Vitam Nutr Res (2002) 72:26–31.10.1024/0300-9831.72.1.26 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]94.

Getahun SM, Chung FL.. Conversion of glucosinolates to isothiocyanates in humans after ingestion of cooked watercress. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (1999) 8:447–51. [PubMed]95.

Conaway CC, Getahun SM, Liebes LL, Pusateri DJ, Topham DKW, Botero-Omary M, et al. Disposition of glucosinolates and sulforaphane in humans after ingestion of steamed and fresh broccoli. Nutr Cancer (2000) 38:168–78.10.1207/S15327914NC382_5 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]96.

Rungapamestry V, Duncan AJ, Fuller Z, Ratcliffe B.. Changes in glucosinolate concentrations, myrosinase activity, and production of metabolites of glucosinolates in cabbage (Brassica oleracea Var. capitata) cooked for different durations. J Agric Food Chem (2006) 54:7628–34.10.1021/jf0607314 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]97.

Rouzaud G, Young SA, Duncan AJ.. Hydrolysis of glucosinolates to isothiocyanates after ingestion of raw or microwaved cabbage by human volunteers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2004) 13:125–31.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-085-3 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]98.

Krul C, Humblot C, Philippe C, Vermeulen M, van Nuenen M, Havenaar R, et al. Metabolism of sinigrin (2-propenyl glucosinolate) by the human colonic microflora in a dynamic in vitro large-intestinal model. Carcinogenesis (2002) 23:1009–16.10.1093/carcin/23.6.1009 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]99.

Elfoul L, Rabot S, Khelifa N, Quinsac A, Duguay A, Rimbault A.. Formation of allyl isothiocyanate from sinigrin in the digestive tract of rats monoassociated with a human colonic strain of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. FEMS Microbiol Lett (2001) 197:99–103.10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10589.x [PubMed] [Cross Ref]100.

Combourieu B, Elfoul L, Delort AM, Rabot S.. Identification of new derivatives of sinigrin and glucotropaeolin produced by the human digestive microflora using 1H NMR spectroscopy analysis of in vitro incubations. Drug Metab Dispos (2001) 29:1440–5. [PubMed]101.

Cheng D-L, Hashimoto K, Uda Y.. In vitro digestion of sinigrin and glucotropaeolin by single strains of Bifidobacterium and identification of the digestive products. Food Chem Toxicol (2004) 42:351–7.10.1016/j.fct.2003.09.008 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]102.

Bheemreddy RM, Jeffery EH.. The metabolic fate of purified glucoraphanin in F344 rats. J Agric Food Chem (2007) 55:2861–6.10.1021/jf0633544 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]103.

Duncan AJ, Milne JA. Rumen microbial degradation of allyl cyanide as a possible explanation for the tolerance of sheep to brassica-derived glucosinolates. J Sci Food Agric (1992) 58:15–9.10.1002/jsfa.2740580104 [Cross Ref]104.

Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Versatile nitrilases: nitrile-hydrolysing enzymes. FEMS Microbiol Lett (1994) 120:217–23.10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07036.x [Cross Ref]105. Michaelsen S, Otte J, Simonsen L-O, Sørensen H. Absorption and degradation of individual intact glucosinolates in the digestive tract of rodents. Acta Agric Scand Sect – Anim Sci (1994) 44:25–37.

106.

Bollard M, Stribbling S, Mitchell S, Caldwell J.. The disposition of allyl isothiocyanate in the rat and mouse. Food Chem Toxicol (1997) 35:933–43.10.1016/S0278-6915(97)00103-8 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]107.

Conaway CC, Jiao D, Kohri T, Liebes L, Chung FL.. Disposition and pharmacokinetics of phenethyl isothiocyanate and 6-phenylhexyl isothiocyanate in F344 rats. Drug Metab Dispos (1999) 27:13–20. [PubMed]108.

Mennicke WH, Kral T, Krumbiegel G, Rittmann N.. Determination of N-acetyl-S-(N-alkylthiocarbamoyl)-L-cysteine, a principal metabolite of alkyl isothiocyanates, in rat urine. J Chromatogr (1987) 414:19–24.10.1016/0378-4347(87)80020-8 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]109.

Ioannou YM, Burka LT, Matthews HB.. Allyl isothiocyanate: comparative disposition in rats and mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol (1984) 75:173–81.10.1016/0041-008X(84)90199-6 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]110.

Jiao D, Ho CT, Foiles P, Chung FL.. Identification and quantification of the N-acetylcysteine conjugate of allyl isothiocyanate in human urine after ingestion of mustard. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (1994) 3:487–92. [PubMed]111.

Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P.. Chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of broccoli sprouts: metabolism and excretion in humans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (2001) 10:501–8. [PubMed]112.

De Brabander HF, Verbeke R. Determination of oxazolidine-2-thiones in biological fluids in the ppb range. J Chromatogr A (1982) 252:225–39.10.1016/S0021-9673(01)88414-4 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]113.

Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P.. Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev (1998) 7:1091–100. [PubMed]114.

Matusheski NV, Juvik JA, Jeffery EH.. Heating decreases epithiospecifier protein activity and increases sulforaphane formation in broccoli. Phytochemistry (2004) 65:1273–81.10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.04.013 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]115.

Banerjee A, Variyar PS, Chatterjee S, Sharma A.. Effect of post harvest radiation processing and storage on the volatile oil composition and glucosinolate profile of cabbage. Food Chem (2014) 151:22–30.10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.055 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]116. Sabir FK. Postharvest quality response of broccoli florets to combined application of 1-methylcyclopropene and modified atmosphere packaging. Agric Food Sci (2012) 21:421–9.

117.

Villarreal-García D, Nair V, Cisneros-Zevallos L, Jacobo-Velázquez DA.. Plants as biofactories: postharvest stress-induced accumulation of phenolic compounds and glucosinolates in broccoli subjected to wounding stress and exogenous phytohormones. Front Plant Sci (2016) 7:45.10.3389/fpls.2016.00045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]118.

Jones RB, Faragher JD, Winkler S. A review of the influence of postharvest treatments on quality and glucosinolate content in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) heads. Postharvest Biol Technol (2006) 41:1–8.10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.03.003 [Cross Ref]119.

Rangkadilok N, Tomkins B, Nicolas ME, Premier RR, Bennett RN, Eagling DR, et al. The effect of post-harvest and packaging treatments on glucoraphanin concentration in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica). J Agric Food Chem (2002) 50:7386–91.10.1021/jf0203592 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]120.

Vallejo F, Tomas-Barberan F, Garcia-Viguera C.. Health-promoting compounds in broccoli as influenced by refrigerated transport and retail sale period. J Agric Food Chem (2003) 51:3029–34.10.1021/jf021065j [PubMed] [Cross Ref]121.

Rybarczyk-Plonska A, Hagen SF, Borge GIA, Bengtsson GB, Hansen MK, Wold A-B. Glucosinolates in broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) as affected by postharvest temperature and radiation treatments. Postharvest Biol Technol (2016) 116:16–25.10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.12.023 [Cross Ref]122.

Badełek E, Kosson R, Adamicki F. The effect of storage in controlled atmosphere on the quality and health-promoting components of broccoli (Brassica oleracea bar. Italica). Veg Crops Res Bull (2013) 77:89–100.10.2478/v10032-012-0018-x [Cross Ref]123.

Song L, Thornalley PJ.. Effect of storage, processing and cooking on glucosinolate content of Brassica vegetables. Food Chem Toxicol (2007) 45:216–24.10.1016/j.fct.2006.07.021 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]124.

Verkerk R, Dekker M, Jongen WMF. Post-harvest increase of indolyl glucosinolates in response to chopping and storage of Brassica vegetables. J Sci Food Agric (2001) 81:953–8.10.1002/jsfa.854 [Cross Ref]125.

Björkman R, Lönnerdal B. Studies on myrosinases III. Enzymatic properties of myrosinases from Sinapis alba and Brassica napus seeds. Biochim Biophys Acta (1973) 327:121–31. [PubMed]126.

Ghawi SK, Methven L, Rastall RA, Niranjan K. Thermal and high hydrostatic pressure inactivation of myrosinase from green cabbage: a kinetic study. Food Chem (2012) 131:1240–7.10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.111 [Cross Ref]127.

Aires A, Carvalho R, Rosa E. Glucosinolate composition of Brassica is affected by postharvest, food processing and myrosinase activity. J Food Process Preserv (2012) 36:214–24.10.1111/j.1745-4549.2011.00581.x [Cross Ref]128.

Tsao R, Yu Q, Potter J, Chiba M.. Direct and simultaneous analysis of sinigrin and allyl isothiocyanate in mustard samples by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Agric Food Chem (2002) 50:4749–53.10.1021/jf0200523 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]129. Quinsac A, Krouti M, Ribaillier D, Deschamps M, Herbach M, Lallemand J, et al. Determination of the total glucosinolate content in rapeseed seeds by liquid chromatography: comparative study between the rapid isocratic and the reference gradient methods by a ring test. Ocl-Ol Corps Gras Lipides (1998) 5:398–406.

130.

Maheshwari PN, Stanley DW, Voort FRVD. Microwave treatment of dehulled rapeseed to inactivate myrosinase and its effect on oil and meal quality. J Am Oil Chem Soc (1980) 57:194–9.10.1007/BF02673937 [Cross Ref]131.

Blok Frandsen H, Ejdrup Markedal K, Martín-Belloso O, Sánchez-Vega R, Soliva-Fortuny R, Sørensen H, et al. Effects of novel processing techniques on glucosinolates and membrane associated myrosinases in broccoli. Pol J Food Nutr Sci (2014) 64:17–25.10.2478/pjfns-2013-0005 [Cross Ref]132.

Islam MN, Zhang M, Adhikari B. The inactivation of enzymes by ultrasound – a review of potential mechanisms. Food Rev Int (2014) 30:1–21.10.1080/87559129.2013.853772 [Cross Ref]133.

Wimmer Z, Zarevúcka M.. A review on the effects of supercritical carbon dioxide on enzyme activity. Int J Mol Sci (2010) 11:233–53.10.3390/ijms11010233 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]134.

Girgin N, El SN. Effects of cooking on in vitro sinigrin bioaccessibility, total phenols, antioxidant and antimutagenic activity of cauliflower (Brassica oleraceae L. var. Botrytis). J Food Compos Anal (2015) 37:119–27.10.1016/j.jfca.2014.04.013 [Cross Ref]135.

Hwang E-S, Thi ND. Impact of cooking method on bioactive compound content and antioxidant capacity of cabbage. Korean J Food Sci Technol (2015) 47:184–90.10.9721/KJFST.2015.47.2.184 [Cross Ref]136.

Vieites-Outes C, López-Hernández J, Lage-Yusty MA. Modification of glucosinolates in turnip greens (Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L.) subjected to culinary heat processes. CYTA – J Food (2016).10.1080/19476337.2016.1154609 [Cross Ref]137.

Ciska E, Drabińska N, Honke J, Narwojsz A. Boiled Brussels sprouts: a rich source of glucosinolates and the corresponding nitriles. J Funct Foods (2015) 19:91–9.10.1016/j.jff.2015.09.008 [Cross Ref]138.

Xu F, Zheng Y, Yang Z, Cao S, Shao X, Wang H.. Domestic cooking methods affect the nutritional quality of red cabbage. Food Chem (2014) 161:162–7.10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.04.025 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]139.

Bongoni R, Verkerk R, Steenbekkers B, Dekker M, Stieger M.. Evaluation of different cooking conditions on broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) to improve the nutritional value and consumer acceptance. Plant Foods Hum Nutr (2014) 69:228–34.10.1007/s11130-014-0420-2 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]140.

Dosz EB, Jeffery EH.. Modifying the processing and handling of frozen broccoli for increased sulforaphane formation. J Food Sci (2013) 78:H1459–63.10.1111/1750-3841.12221 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]141.

Fiore A, Di M, Cavella S, Visconti A, Karneili O, Bernhardt S, et al. Chemical profile and sensory properties of different foods cooked by a new radiofrequency oven. Food Chem (2013) 139:515–20.10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.028 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]142.

Ghawi SK, Methven L, Niranjan K.. The potential to intensify sulforaphane formation in cooked broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) using mustard seeds (Sinapis alba). Food Chem (2013) 138:1734–41.10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.10.119 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]143.

Martínez-Hernández GB, Artés-Hernández F, Gómez PA, Artés F. Induced changes in bioactive compounds of kailan-hybrid broccoli after innovative processing and storage. J Funct Foods (2013) 5:133–43.10.1016/j.jff.2012.09.004 [Cross Ref]144.

Park M-H, Valan A, Park N-Y, Choi Y-J, Lee S-W, Al-Dhabi NA, et al. Variation of glucoraphanin and glucobrassicin: anticancer components in Brassica during processing. Food Sci Technol (2013) 33:624–31.10.1590/S0101-20612013000400005 [Cross Ref]145.

Jones RB, Frisina CL, Winkler S, Imsic M, Tomkins RB. Cooking method significantly effects glucosinolate content and sulforaphane production in broccoli florets. Food Chem (2010) 123:237–42.10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.04.016 [Cross Ref]146.

Francisco M, Velasco P, Moreno DA, García-Viguera C, Cartea ME. Cooking methods of Brassica rapa affect the preservation of glucosinolates, phenolics and vitamin C. Food Res Int (2010) 43:1455–63.10.1016/j.foodres.2010.04.024 [Cross Ref]147.

Yuan G-F, Sun B, Yuan J, Wang Q-M.. Effects of different cooking methods on health-promoting compounds of broccoli. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B (2009) 10:580–8.10.1631/jzus.B0920051 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]148.

Roland N, Rabot S, Nugon-Baudon L.. Modulation of the biological effects of glucosinolates by inulin and oat fibre in gnotobiotic rats inoculated with a human whole faecal flora. Food Chem Toxicol (1996) 34:671–7.10.1016/0278-6915(96)00038-5 [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

Articles from Frontiers in Nutrition are provided here courtesy of Frontiers Media SA

complementair, voedingsupplementen, fruit en groenten, antioxidanten, voeding, literatuurlijst, niet-toxische middelen en behandelingen, biobeschikbaarheid, opname door lichaam van voedingsstoffen, preventie, voorkomen van recidief

Gerelateerde artikelen

- Wat beïnvloedt de opname van vitamines en mineralen? Zijn capsules beter dan tabletten? Alf Knutzen directeur van Alfytal schrijft hierover interessant artikel

- Referentiegids effecten van voedingsuppletie bij kanker

- Algemeen: effecten van voedingswijzen, fruit en groenten, antioxidanten enz. op voorkomen van kanker en als aanvulling bij behandelngen van kanker: een overzicht

- Aminozuren - BCAA verbeteren significant het herstel van de leverfuncties na RFA - Radio Frequency Ablation van primaire leverkanker

- Anti kanker effectiviteit van voedingsstoffen uit groenten wordt bepaald door manier van bewaren en bereiding. Stomen is beter dan koken, rauw soms het beste

- Anti-oxidanten via voedingssupplementen naast chemo verminderen de bijwerkingen verbetert de effectiviteit van chemo en zorgt voor betere overall overleving blijkt uit grote meta-analyse van 93 gerandomiseerde studies

- Antioxidanten hebben geen negatieve invloed op effecten bij chemokuren, in tegendeel: antioxidanten verbeteren de kwaliteit van leven door verminderde bijwerkingen en verbeteren de effectiviteit van de chemokuren aanzienlijk.

- Arts-bioloog drs. E. Valstar analyseert rapport van KWF over relatie voeding en kanker. Deel 1: De rol van fruit en groente bij kanker.

- Arts-bioloog drs. E. Valstar: een aantal artikelen van zijn hand bij elkaar gezet waaronder ook enkele publicaties in kranten of tijdschriften

- ATRA - all-trans-retinoic-acid - retinionezuur voorkomt en vermindert sterk de tumorgroei bij darmkanker blijkt uit dierstudies en darmflora van darmkankerpatienten

- Avemar, een gefermenteerd tarwekiem extract gegeven als aanvulling bij chemo (dacarbazine) verlengt overlevingstijd bij melanoompatienten en bij darmkankerpatienten met extra groot risico.

- Bestraling: Rectale schade door bestraling kan met extra vitamines E. en C. significant verminderd en sneller hersteld worden, blijkt uit studie met 20 patiënten.

- Beta caroteen aanvullend op bestraling bij prostaatkanker blijkt veilig en geeft zelfs 3 procent meer 10 jaars- overlevingen, bljikt uit placebo gecontroleerde gerandomiseerde studie

- Bosbessen extract doet agressieve borstkankertumoren slinken en stopt groei, blijkt uit dierstudies

- Broccoli verliest beschermende werking van sulfarofaan als het lang gekookt wordt. Beter is broccoli korter koken/stomen of nog beter rauw eten.

- Calcium, 1000 mg per dag, vermindert significant de kans op overlijden aan alle oorzaken, met name vrouwen profiteren van calcium gebruik ofwel via extra suppletie of via voeding

- Calorie-arm plantaardig dieet dat vasten nabootst plus vitamine C samen gebruikt blijkt uitstekende niet-toxische behandeling voor KRAS gemuteerde kankercellen van spijsverteringskanker, waaronder darmkanker en alvleesklierkanker.

- Chronische ziekten behandelen met voeding zou algemene richtlijn moeten zijn stelt ZonMw na onderzoek van Wageningen University & Research en de Universiteit van Groningen

- Coriolus Versicolor bestrijdt succesvol HPV virus bij patienten met baarmoederhalstumoren en reduceert grootte tumoren en graad van kwaadaardigheid. Na 1 jaar was 91% van het HPV virus verdwenen in suppletiegroep

- Eiwitsupplement met 2,02 gram EPA en 0,92 gram DHA ( n-3 meervoudig onverzadigde vetzuren (FA)) per dag tijdens de behandelingsperiode verbetert significant de levenskwaliteit bij patienten met niet-klein-cellige longkanker (NSCLC)

- Foliumzuur gebruik door zwangere vrouwen voorkomt klassiek autisme met ca. 40 procent

- Gember capsules innemen enkele dagen voor en na toediening van chemo geeft beduidend minder misselijkheid en overgeven door de chemo. Aldus een dubbelblinde gerandomiseerde fase III studie met 644 kankerpatienten

- Honing heeft versneld genezende werking op wonden en lijkt ook anti-oxidante werking te hebben en lijkt alternatief voor suiker

- IAA - Intraveneuze injecties met vitamine C. Een overzicht van artikelen en studies

- Immuunversterkende voeding waaronder glutamine en arginine vooraf aan operatie van spijsverteringskanker significant zorgt voor minder infecties en significant korter verblijf in ziekenhuis en betere weerstand

- Menatetrenone een middel analoog aan de vitamine K2 geeft significant langere overleving bij patiënten met levertumoren welke succesvol operatief zijn verwijderd.

- Mitochondriaal-stamcel-verband (MSCC) blijkt een belangrijk element te zijn in de therapeutische benadering van kanker via orthomoleculaire aanpak. Blijkt uit nieuwe studie met protocol hoe dat te bewerkstelligen

- Multivitamines met mineralen - MVM - vermindert kans op overlijden met 30 procent voor oudere vrouwen met borstkanker

- N-acetylcysteïne - NAC - vergroot significant de kans op een geslaagde levertransplantatie

- Selenium kan nierschade voorkomen bij mensen die per infuus cisplatin krijgen.

- Spirulina heeft opmerkelijk goed effect op klinische en stofwisselingswaarden (metabole parameters) bij de ziekte van Alzheimer

- Artikelen met Vitamine-D - Calcifediol in de hoofdrol: overzicht van artikelen en studies

- Vitamine E beschermt tegen neuropathische schade en klachten (zenuwpijn en aantasting van de zenuwen)bij chemokuren met paclitaxel

- vitamine K, zowel uit voeding als via suppletie, voorkomt botproblemen zoals botbreuken en osteoperose en kan belangrijk zijn voor vrouwen met borstkanker die een hormoonkuur volgen.

- Vitamine C, E, Zink, Betacaroteen en Selenium als aanvulling op dageljkse voeding voorkomt ontwikkelen van kanker, aldus 7,5 jarige studie onder 13.000 mensen.

- Vlees en vleesproducten zijn een risico voor het krijgen van kanker. Een aantal studies en artikelen bij elkaar gezet over risico van te veel (rood) vlees eten

- Verslag congres georganiseerd in 2001 door het Linnus Paulus Instituut

- Antioxidanten, voeding en vitamines en mineralen als preventie en medicijn tegen kanker: een aantal belangrijke studies en artikelen bij elkaar gezet

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Anti kanker effectiviteit van voedingsstoffen uit groenten wordt bepaald door manier van bewaren en bereiding. Stomen is beter dan koken, rauw soms het beste"