At a median follow-up of 41.9 months, the 3-year event-free survival (EFS) rate was 86.1% with the combination vs 76.0% with standard therapy (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.38-0.92; P = .019).

The 3-year rate of distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) was 90.3% with the combination vs 82.8% with chemoradiotherapy alone (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.98; P = .039). The 3-year rates of locoregional recurrence-free survival (LRFS) were 93.4% and 86.8% with the combination and chemoradiotherapy alone, respectively (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27-0.97; P =.038).

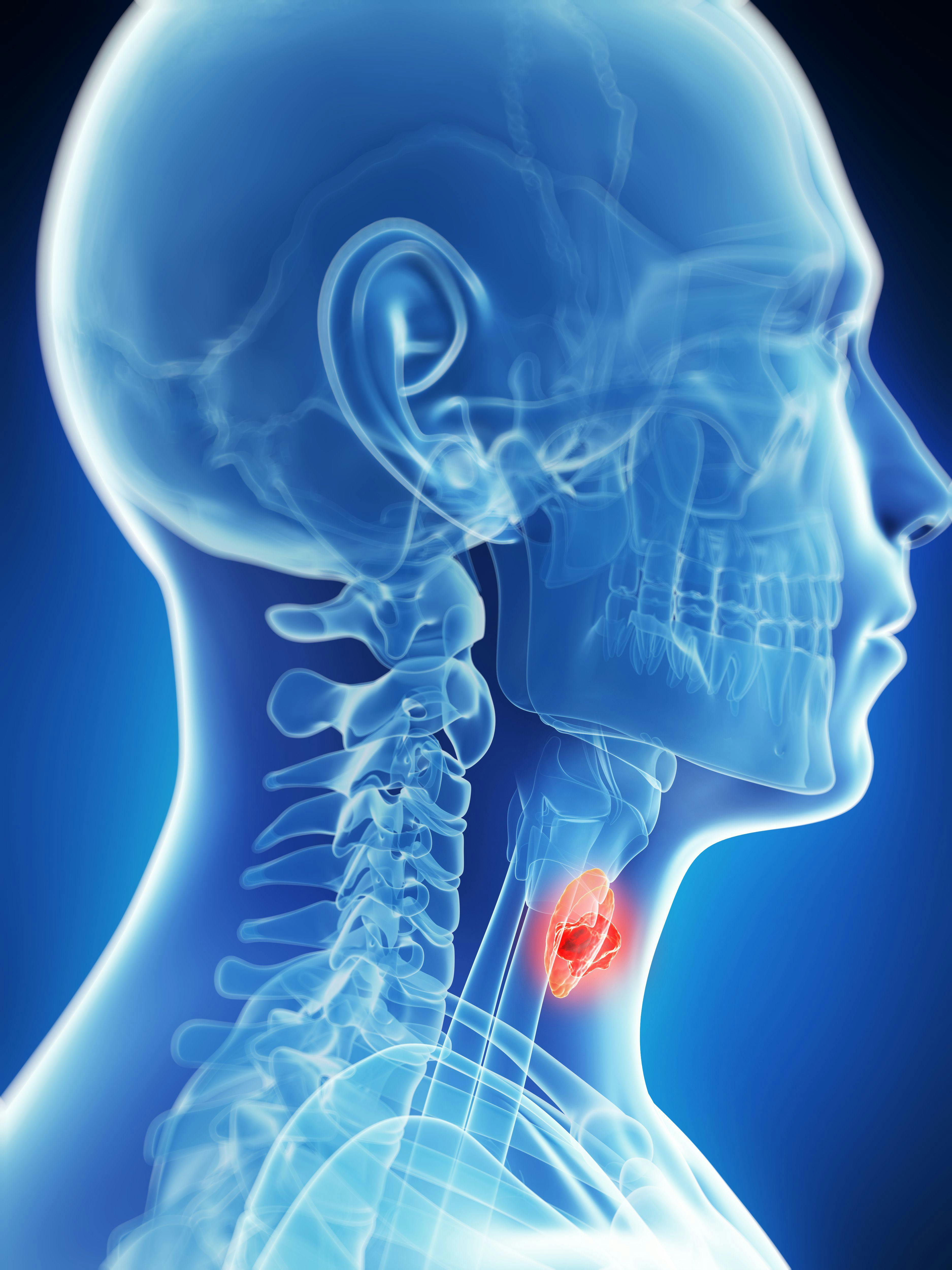

“This CONTINUUM trial supports sintilimab combined with chemoradiotherapy as a new standard of care for high-risk locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” lead study author Jun Ma, MD, MSc, professor and vice president, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, said during a presentation of the data.

Locoregionally advanced disease represents approximately 75% of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Standard therapy consists of induction chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy. However, 20% of patients will develop recurrence or metastasis.

The study enrolled patients with stage III to IV nasopharyngeal carcinoma excluding T3 to T4N0 and T3N1 disease. A total of 425 patients were randomly assigned to 200 mg of sintilimab every 3 weeks for 12 cycles plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy (n = 210) or standard therapy with chemoradiotherapy alone (n = 215). These patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis for efficacy. Safety was evaluated in the 209 and 214 patients who started treatment with sintilimab and chemoradiotherapy alone, respectively.

EFS served as the primary end point. Secondary end points included OS, LRFS, DMFS, toxicity, health-related quality of life (QOL), and biomarkers.

Induction chemotherapy consisted of gemcitabine 1 g/m2 on day 1 and 8 and dose dense platinum 80 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for 3 cycles, followed by 100 mg/m2 of dose dense platinum on day 1 every 3 weeks for 2 cycles. Intensity modulated radiotherapy was administered at 70 Gy in 33 fractions/day for 5 consecutive days each week.

When presenting baseline characteristics in the ITT population, Ma called attention to the breakdown of T category, highlighting that 41.4% (n = 87) and 45.7% (n = 96) of patients in the sintilimab arm had T3 and T4 disease, respectively, compared with 36.2% (n = 78) and 49.3% (n = 106) of those in the chemoradiotherapy alone arm, respectively. Moreover, 45.2% (n = 95), 34.3% (n = 72), and 70.4% (n = 148) of patients in the sintilimab arm had N2, N3, or IVA disease, respectively. N2, N3, and IVA disease was documented in 46.5% (n = 100), 31.2% (n = 67), and 70.2% (n = 151) of patients in the chemoradiotherapy-alone arm, respectively.

Regarding compliance to therapy, 70.8% of patients completed all 12 cycles of sintilimab. The rate of patients who completed less than 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 9, and 10 to 11 cycles of sintilimab was 9.6%, 12.0%, 3.3%, and 4.3%, respectively. Reasons for discontinuation (n = 61; 29.2%) included patient refusal (n = 24; 11.5%), adverse effects (AEs; n = 22; 10.5%), COVID-19 (n = 8; 3.8%), disease progression (n = 5; 2.4%), or death (n = 2; 1.0%).

The percentages of patients who completed induction chemotherapy, concurrent dose dense platinum, and concurrent dose dense platinum at a dose of at least 200 mg/m2 were 92%, 83%, and 76% in the sintilimab arm, vs 92%, 91%, and 80% in the chemoradiotherapy-alone arm. A similar percentage of patients completed radiotherapy in the sintilimab and chemoradiotherapy alone arms, at 97% and 98%, respectively.

Subgroup analysis showed that patients with N1 disease derived the most benefit from the combination, with a hazard ratio of 0.14 (95% CI, 0.03-0.61) for recurrence or death.

Ma noted that OS was not statistically significant between the 2 arms, requiring further follow-up.

Regarding safety, all patients experienced AEs. Grade 3/4 and grade 5 AEs occurred in 74.2% (n = 155) and 0.95% (n = 2) of patients in the experimental arm vs 65.4% (n = 140) and 0.5% (n = 1) of those in the standard therapy arm. AEs leading to discontinuation with chemotherapy occurred in 12.0% (n = 25) and 6.5% (n = 14) of patients in the experimental and standard therapy arms, respectively. AEs leading to discontinuation with radiation occurred in 2 patients (0.95%) in the sintilimab arm and 1 patient (0.5%) in the standard therapy arm.

Common AEs in the sintilimab and chemoradiotherapy-alone arms, respectively, included anemia (93.3% vs 92.1%, leukopenia (87.1% vs 82.7%), nausea (86.1% vs 85.0%), stomatitis/mucositis (85.2% vs 84.6%), anorexia (84.7% vs 86.0%), dry mouth (78.5% vs 83.2%), neutropenia (72.2% vs 66.4%), dermatitis (71.3% vs 68.2%), fatigue (70.8% vs 72.9%), vomiting (64.6% vs 62.1%), weight loss (63.2% vs 65.4%), deafness or otitis (62.7% vs 58.9%), and constipation (58.9% vs 59.3%).

“Adverse effects are higher [with the addition of sintilimab] but manageable,” Ma said.

Immune-related AEs (irAEs) that occurred in the sintilimab arm (59.8%; n = 125) included rash (28.2%), hypothyroidism (27.8%), pruritus (24.9%), hyperthyroidism (19.1%), amylase increase (11.5%), and allergic reaction (3.3%). Grade 3/4 and 5 events occurred in 9.6% (n = 20) and 0.95% (n = 2) of patients, respectively. irAEs leading to discontinuation of chemotherapy and radiation therapy occurred in 6 (2.9%) and 2 patients (0.95%), respectively.

Notably, QOL, assessed with the EORTC QLQ C30 questionnaire, was comparable between the 2 arms at 3 years.

Disclosures: Ma reported research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation and Varian Medical Systems.

Reference

Ma J, Sun Y, Liu X, et al. PD-1 blockade with sintilimab plus induction chemotherapy (IC) and concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) versus IC and CCRT in locoregionally-advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (LANPC): a multicenter, phase 3, randomized controlled trial (CONTINUUM). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 17):LBA6002. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.17_suppl.LBA6002

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Immuuntherapie met sintilimab na chemotherapie verhoogt recidiefvrije overleving met 10 procent (76 vs 86 procent) in vergelijking met chemo + bestraling bij neuskanker stadium III en IV op 3-jaars meting"