Als u de informatie op kanker-actueel waardeert wilt u ons misschien steunen met een donatie op

RABO 37.29.31.138 t.n.v. Stichting Gezondheid Actueel in Terneuzen.

Onze IBANcode is NL79 RABO 0372 9311 38

BIC/SWIFTCODE RABONNL2U

Wij zijn een ANBI organisatie, dus uw donatie is in principe aftrekbaar voor de inkomstenbelasting. Ook kunt u als donateur voordeel krijgen bij verschillende bedrijven.

17 juni 2019: lees ook dit artikel:

Zie ook in gerelateerde artikelen

Hier het commentaar van arts-bioloog drs. Engelbert Valstar op onderstaande studiepublicatie:

29 maart 2019: Aanvullend commentaar:

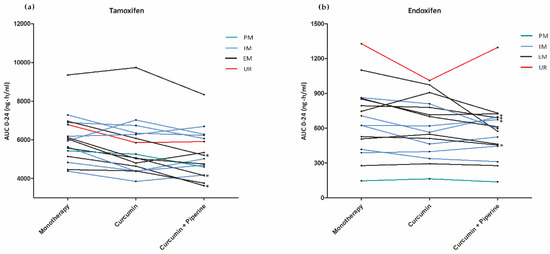

Curcumine met peper verlaagt tamoxifenspiegel iets. Curcumine alleen niet aantoonbaar. Het bewijst dus dat zwarte peper de tamoxifenspiegel verlaagt. Los van dat er geen placebocorrectie is, is de hoofdconclusie fout. Dit is wel een enorme blunder: het onderzoek zegt dus zelf niets ten nadele van curcumine. Ze hadden een groep met alleen zwarte peper mee moeten nemen.

Als we de Bonferroni-correctie in maximale gestrengheid hier toepassen: tamoxifen en een metaboliet op 2 momenten na t=0, met en zonder piperine dan zijn er 8 'vergelijkingen'; de significantiegrens ligt dan bij 0,05/8= < 0,007 ; elke significantie verdwijnt dan

Kees, mijn voorlopige commentaar: De spiegels van tamoxifen en een metaboliet zijn lager met curcumine en piperine, maar niet aantoonbaar met curcumine alleen. Omdat er naar meerdere variabelen is gekeken en het aantal patienten klein is, is de significantie met curcumine en piperine veel geringer dan gesuggereerd. Voorts betreft het een zeer hoge dosis. Drie keer 1200 mg curcumine : 3600 mg zit normaliter in let wel 72 gram curcumapoeder. Daarbij komt dat er niet naar een biologische eindmaat is gekeken, bijvoorbeeld het aantal tumorregressies bij gebruik van tamoxifen met/zonder curcumine etc. Verder is er van placebocorrectie geen sprake. Daarbij komt verder dat modelmatig onderzoek laat zien dat curcumine de gevoeligheid van borstkankercellen voor tamoxifen kan vergroten (PMID 23299550)

Mijn conclusie is dat het onderzoek geen harde conclusies over een mogelijke interactie toelaat. Mijn ervaring is dat als er een interactie ongunstig is, er 19 gunstige tegenover staan. Een expliciet ongunstige is er bijvoorbeeld tussen vitamine C en Velcade. Niet voor niets heb ik per cytostaticum, maar ook bij bestraling rijtjes gunstige en ongunstige interacties.

27 maart 2019: Bron: AD en Cancers 2019, 11(3), 403; doi: 10.3390/cancers11030403

Onderzoekers van het Erasmus MC komen vandaag met een waarschuwing tegen kurkuma gebruik (curcumine) naast hromoontherapie (Tamoxifen) door borstkankerpatiënten. Zij krijgen van het Algemeen Dagblad alle ruimte om hun bevindingen uit een bloedwaardenstudie met 16 borstkankerpatiënten (!!!!) breed uit te meten en voor het gebruik van curcumine - kurkuma supplementen te waarschuwen. (Zoals ze eerder deden voor St. Janskruid).

Echter de onderzoekers vonden alleen dat er bij een paar patiënten in het bloed minder van de werkzame stof uit Tamoxifen en Endoxifen aanwezig was en ook 7 procent tot 12 procent (met zwarte peper) van de curcumine (Redactie: blijkbaar wordt curcumine dus wel degelijk opgenomen in het bloed in tegenspraak dus met wat dr. Timmermans beweert, maar dit terzijde) De onderzoekers hebben echter niet getest of kunnen constateren dat de patienten ook daadwerkelijk minder reageerden op de verandering in de bloedwaarden.

Gezien alle onderstaande informatie is de boodschap van de onderzoekers van het Erasmus echt paniekzaaien om niets naar mijn mening. Zie ook reactie van arts-bioloog drs. Engelbert Valstar bovenaan dit artikel

Lees het volledige studierapport: Impact of Curcumin (with or without Piperine) on the Pharmacokinetics of Tamoxifen

In een andere laboratoriumstudie blijkt namelijk juist wel dat curcumine - kurkuma juist de werking van tamoxifen versterkt:

Maar veel belangrijker lijkt deze reviewstudie uit 2018:

Role of curcumin in regulating p53 in breast cancer: an overview of the mechanism of action

die aantoont dat curcumine wel degelijk effect heeft op bepaalde mutaties in de P53, (ca. 50 procent van alle kankerpatienten met een recidief en / of uitzaaiingen hebben een afwijking in het P53 gebied) Het voorkomt en herstelt bepaalde vorming van essentiële mutaties (Uit de conclusie: The numerous health benefits of curcumin, its cost-effectiveness, and its ability to target multiple components in BC make it an ideal agent for further development to produce more effective therapies against BC. )

Uit het abstract:

Curcumin is a natural product, extracted from the roots of Curcuma longa, and possesses various biological effects including anticancer activity. Previous studies proved the ability of curcumin to modulate several signaling pathways and biomolecules in cancer. Safety and cost-effectiveness are additional inevitable advantages of curcumin. This review summarizes the effects of curcumin as a regulator of p53 in BC and the key molecular mechanisms of this regulation.

Nog een citaat uit dit studierapport:

Curcumin can induce apoptosis in a p53- independent manner, especially in cancer cells that lack a functional p53 protein by downregulating pro-survival protein (Bcl-2) and p38 MAPK.118,119 This dietary natural compound inhibits the p300-mediated acylation of p53 that interacts with the p300/CBP complex to enhance its transcriptional effect.120 Additionally, other molecular targets for curcumin were reported in several studies testing its anticancer effect against breast cancer.121–125 Figure 3 summarizes the main regulatory points of curcumin in BC. In addition, in vitro studies on various BC cell lines in addition to a brief summary about the inhibitory effects of curcumin in animal models are listed in Tables 1 and and2,2, respectively.

Ook Michal Heger (AMC) heeft ook wel kritiek op de uitlatingen van zijn collega's in het Erasmus MC in het Algemeen Dagblad artikel:

Uit het AD artikel: Michal Heger deed jarenlang onderzoek naar curcumine, de werkzame stof uit kurkuma, bij het AMC. Hij noemt de studie van zijn Rotterdamse collega’s ‘een superbelangrijke vinding’. Toch vraagt hij om de specerij nu niet af te doen als ‘totaal waardeloos’. Curcumine kan volgens hem bij enkele andere kankersoorten de chemotherapie wél gunstig beïnvloeden. ,,Curcumine werkt niet genezend bij kanker. Dat is een doodzieke kankerpatiënt valse hoop geven, maar het kan bij verschillende kankersoorten ook de bijwerkingen van de chemo verzachten. Denk aan misselijkheid en pijn.”

Hier het artikel in het Algemeen Dagblad:

Onderzoekers Erasmus MC: pas op met kurkuma

Onder borstkankerpatiënten leeft het idee dat kurkuma kanker kan bestrijden. Maar pas op, zeggen onderzoekers van het Erasmus MC na een nieuwe studie. Deze specerij tast de werking van een veelgebruikt kankermedicijn aan.

Hanneke van Houwelingen

Het is een hype die al jaren hardnekkig standhoudt: de specerij kurkuma (geelwortel) die in de Aziatische keuken wordt gebruikt zou een geneeskrachtige werking hebben op kanker. Curcumine, de werkzame stof uit kurkuma, zou in staat zijn om kankercellen op te ruimen. Bewijs hiervoor werd in dierproeven gevonden.

Reden voor veel borstkankerpatiënten om extra veel van dit gele poeder over hun eten te strooien of capsules met kurkuma te slikken. ,,Veel patiënten redeneren: als je het ook kunt eten in een curry, kan het geen kwaad. Als het dan ook helpt tegen kanker, is dat mooi meegenomen. Maar daar komen wij van terug. Doe het niet”, waarschuwt arts-onderzoeker Koen Hussaarts van het Erasmus MC.>>>>>>lees verder het hele artikel

Het studierapport van de onderzoekers van het Erasmus MC is gratis in te zien: Impact of Curcumin (with or without Piperine) on the Pharmacokinetics of Tamoxifen

Hier het abstract plus referentielijst van deze studie:

In conclusion, the exposure to tamoxifen and endoxifen was significantly decreased by concomitant use of curcumin (+/− piperine). Therefore, co-treatment with curcumin could lower endoxifen concentrations below the threshold for efficacy (potentially 20–40% of the patients), especially in EM patients.

Cancers 2019, 11(3), 403; doi: 10.3390/cancers11030403

Abstract

:Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in globocan 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative, G. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005, 365, 1687–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Damery, S.; Gratus, C.; Grieve, R.; Warmington, S.; Jones, J.; Routledge, P.; Greenfield, S.; Dowswell, G.; Sherriff, J.; Wilson, S. The use of herbal medicines by people with cancer: A cross-sectional survey. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 927–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.A.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P. Curcumin: The story so far. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 1955–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoba, G.; Joy, D.; Joseph, T.; Majeed, M.; Rajendran, R.; Srinivas, P.S. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkhorst, L.; Mathijssen, R.H.; Jager, A.; van Gelder, T. Individualization of tamoxifen therapy: Much more than just cyp2d6 genotyping. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015, 41, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, M.; Citi, V.; Crucitta, S.; Rofi, E.; Belcari, F.; van Schaik, R.H.; Danesi, R. Pharmacogenetics of cyp2d6 and tamoxifen therapy: Light at the end of the tunnel? Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 107, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.A.; Lee, W.; Choi, J.S. Effects of curcumin on the pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen and its active metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, in rats: Possible role of cyp3a4 and p-glycoprotein inhibition by curcumin. Pharmazie 2012, 67, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bahramsoltani, R.; Rahimi, R.; Farzaei, M.H. Pharmacokinetic interactions of curcuminoids with conventional drugs: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 209, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arye, E.; Samuels, N.; Goldstein, L.H.; Mutafoglu, K.; Omran, S.; Schiff, E.; Charalambous, H.; Dweikat, T.; Ghrayeb, I.; Bar-Sela, G.; et al. Potential risks associated with traditional herbal medicine use in cancer care: A study of middle eastern oncology health care professionals. Cancer 2016, 122, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, H.; Jing, T.; Wan-Hua, Y.; Juan, S.; Xiao-Lei, L.; Wen-Xing, P. P-gp induction by curcumin: An effective antidotal pathway. J. Bioequivalence Bioavailab. 2013, 5, 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, M.V.; de Oliveira, V.; Raymundo, S.; Staudt, D.E.; Gossling, G.; Biazus, J.V.; Cavalheiro, J.A.; Rosa, D.D.; Mathy, G.; Wallemacq, P.; et al. Cyp3a4*22 is related to increased plasma levels of 4-hydroxytamoxifen and partially compensates for reduced cyp2d6 activation of tamoxifen. Pharmacogenomics 2015, 16, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekstra, M.H.; Klumpen, H.J.; Lolkema, M.P.; Yu, H.; Kloth, J.S.; Gelderblom, H.; van Schaik, R.H.; Gurney, H.; Swen, J.J.; Huitema, A.D.; et al. Association analysis of genetic polymorphisms in genes related to sunitinib pharmacokinetics, specifically clearance of sunitinib and su12662. Clin. Pharm. 2014, 96, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volak, L.P.; Ghirmai, S.; Cashman, J.R.; Court, M.H. Curcuminoids inhibit multiple human cytochromes p450, udp-glucuronosyltransferase, and sulfotransferase enzymes, whereas piperine is a relatively selective cyp3a4 inhibitor. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1594–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, X.L.; Takahashi, K.; Tanaka, K.; Tougou, K.; Qiu, F.; Komatsu, K.; Takahashi, K.; Azuma, J. Curcuma drugs and curcumin regulate the expression and function of p-gp in caco-2 cells in completely opposite ways. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 358, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, R.; Lowery, R.P.; Calvanese, A.V.; Joy, J.M.; Purpura, M.; Wilson, J.M. Comparative absorption of curcumin formulations. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.A.; Euden, S.A.; Platton, S.L.; Cooke, D.N.; Shafayat, A.; Hewitt, H.R.; Marczylo, T.H.; Morgan, B.; Hemingway, D.; Plummer, S.M.; et al. Phase i clinical trial of oral curcumin: Biomarkers of systemic activity and compliance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6847–6854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Back, S.Y.; Han, H.K. Piperine-mediated drug interactions and formulation strategy for piperine: Recent advances and future perspectives. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedada, S.K.; Boga, P.K. The influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine, a p-glycoprotein substrate, in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 73, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madlensky, L.; Natarajan, L.; Tchu, S.; Pu, M.; Mortimer, J.; Flatt, S.W.; Nikoloff, D.M.; Hillman, G.; Fontecha, M.R.; Lawrence, H.J.; et al. Tamoxifen metabolite concentrations, cyp2d6 genotype, and breast cancer outcomes. Clin. Pharm. 2011, 89, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, P.; Balleine, R.L.; Lee, C.; Gao, B.; Balakrishnar, B.; Menzies, A.M.; Yeap, S.H.; Ali, S.S.; Gebski, V.; Provan, P.; et al. Dose escalation of tamoxifen in patients with low endoxifen level: Evidence for therapeutic drug monitoring-the tade study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3164–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koolen, S.L.; Bins, S.; Mathijssen, R.H. Individualized tamoxifen dose escalation-letter. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binkhorst, L.; Mathijssen, R.H.; Ghobadi Moghaddam-Helmantel, I.M.; de Bruijn, P.; van Gelder, T.; Wiemer, E.A.; Loos, W.J. Quantification of tamoxifen and three of its phase-i metabolites in human plasma by liquid chromatography/triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 56, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, N.G.; Rosing, H.; Schellens, J.H.; Linn, S.C.; Beijnen, J.H. Tamoxifen dose and serum concentrations of tamoxifen and six of its metabolites in routine clinical outpatient care. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 143, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, D. Statistical Considerations for a Cross-Over Study Where the Outcome is a Measurement. Available online: http://hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size/js/js_crossover_quant.html (accessed on 12 January 2017).

- Agency, E.M. Guideline on the Investigation of Bioequivalence. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000370.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580032ec5 (accessed on 12 January 2017).

- Kenward, M.G.; Jones, B. Design and Analysis of Cross-Over Trials; Chapman&Hall/CRC monographs: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients | 16 (100) |

| Randomization sequence | |

| - ABC | 9 (56) |

| - CBA | 7 (44) |

| Adjuvant tamoxifen treatment | 16 (100) |

| Age (Median, IQR) | 45 (42–58) |

| Sex | |

| - Female | 15 (94) |

| - Male | 1 (6) |

| Race | |

| - Caucasian | 15 (94) |

| - Arabic | 1 (6) |

| Height (Median, IQR) | 171 (167–176) |

| Weight (Median, IQR) | 73 (65–91) |

| BMI (Median, IQR) | 25 (23–29) |

| WHO Performance Status | |

| - 0 | 13 (81) |

| - 1 | 3 (19) |

| Previous chemotherapy | |

| - Yes | 12 (75) |

| ○ TAC | 2 (13) |

| ○ AC - paclitaxel | 4 (25) |

| ○ FEC - docetaxel | 6 (37) |

| - No | 4 (25) |

| Previous RTx | |

| - Yes | 10 (63) |

| - No | 6 (37) |

| Tamoxifen dose | |

| - 20 mg | 15 (94) |

| - 30 mg | 1 (6) |

| Genotype | |

| - CYP3A4*22 | |

| ○ EM | 16 (100) |

| - CYP2D6 | |

| ○ EM | 7 (44) |

| ○ IM | 7 (44) |

| ○ PM | 1 (6) |

| ○ UM | 1 (6) |

| PK Parameters | Tamoxifen Monotherapy (A) | Tamoxifen + Curcumin (B) | Tamoxifen + Curcumin + Piperine (C) | Relative Difference A vs B (95%CI) | p-Value | Relative Difference (A vs C) (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | |||||||

| AUC0–24h | 5951 (20) | 5460 (24) | 5171 (23) | −8.0% (−14.1 to −1.4) |

0.02 | −12.8% (−19.2 to −5.9) |

<0.01 |

| Ctrough | 213 (27) | 198 (28) | 187 (24) | −7.1% (−17.1 to +4.0) |

0.25 | −12.2% (−21.5 to −1.8) |

0.02 |

| Cmax | 356 (16) | 324 (21) | 313 (22) | −8.4% (−16.4 to +0.5) |

0.07 | −11.1% (−18.1 to −3.6) |

<0.01 |

| Tmax | 2.4 (1.9 to 3.1) |

2.4 (1.9 to 3.0) |

2.7 (1.9 to 3.8) |

0.74 | 0.34 | ||

| Endoxifen | |||||||

| AUC0–24h | 597 (59) | 556 (52) | 518 (54) | −7.7 % (−15.4 to +0.7) |

0.07 | −12.4% (−21.9 to −1.9) |

0.02 |

| Ctrough | 25 (60) | 23 (53) | 21 (55) | −5.6 % (−15.6 to +5.5) |

0.43 | −12.4% (−20.9 to −3.0) |

0.01 |

| Cmax | 31 (56) | 28 (50) | 27 (51) | −7.1% (−16.3 to +3.2) |

0.20 | −9.8% (−20.1 to +1.8) |

0.10 |

| Tmax | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.0) |

1.7 (1.2 to 2.6) |

1.8 (1.1 to 3.1) |

0.88 | 0.62 | ||

| 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen | |||||||

| AUC0–24h | 113 (31) | 106 (24) | 103 (28) | −6.3 % (−11.6 to −0.73) |

0.03 | −8.2% (−17.0 to +1.6) |

0.11 |

| Ctrough | 4.4 (34) | 4.2 (26) | 4.1 (28) | −4.3 % (−12.3 to +4.4) |

0.45 | −7.3 (−17.6 to +4.3) |

0.26 |

| Cmax | 6.0 (32) | 5.4 (26) | 5.4 (31) | −10.0% (−16.8 to −2.6) |

<0.01 | −8.8% (−20.0 to +4.0) |

0.20 |

| Tmax | 2.7 (1.9 to 3.9) |

2.4 (1.8 to 3.3) |

2.8 (2.0 to 3.8) |

0.42 | 0.37 | ||

| N-desmethyl-tamoxifen | |||||||

| AUC0–24h | 11596 (21) | 10766 (24) | 10084 (31) | −7.0% (−13.1 to −0.6) |

0.03 | −12.4% (−22.3 to −1.3) |

0.03 |

| Ctrough | 463 (28) | 430 (29) | 411 (32) | −7.2% (−15.0 to +1.2) |

0.10 | −10.9% (−21.6 to +1.3) |

0.08 |

| Cmax | 602 (21) | 556 (24) | 540 (32) | −7.2% (−14.9 to +1.1) |

0.09 | −9.7% (−20.2 to +2.3) |

0.12 |

| Tmax | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.7) |

1.7 (1.2 to 2.4) |

2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) |

0.24 | 0.88 | ||

| PK Parameters | Tamoxifen Monotherapy (A) | Tamoxifen + Curcumin (B) | Tamoxifen + Curcumin + Piperine (C) | Relative Difference A vs B (95%CI) | p-Value | Relative Difference A vs C (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate Metabolizers (IM) | |||||||

| Tamoxifen AUC0–24h | 5795 (4895–6859) |

5427 (4313–6830) |

5518 (4679–6508) |

−7.2% (−18.2 to +5.4) |

0.19 | −5.3% (−13.1 to +3.1) |

0.16 * |

| Tamoxifen Ctrough | 200 (160–251) |

191 (146–249) |

199 (167–237) |

−5.9% (−20.9to +11.9) |

0.41 | −1.3% (−15.3 to 15.1) |

0.84 * |

| Endoxifen AUC0–24h | 523 (362–755) |

472 (339–656) |

477 (340–669) |

−9.4% (−21.7 to +4.8) |

0.14 | −10.3% (−23.5 to 5.3) |

0.14 |

| Endoxifen Ctrough | 21 (14–32) |

19 (13–27) |

19 (14–27) |

−10.7% (−28.2 to 11.2) |

0.24 | −8.3% (−27.2 to 15.4) |

0.38 |

| Extensive Metabolizers (EM) | |||||||

| Tamoxifen AUC0–24h | 6077 (4882–7565) |

5471 (4247–7047) |

4836 (3720–6288) |

−10.3% (−19.7 to +0.3) |

0.06 | −22.0% (−29.0 to −4.2) |

<0.01 * |

| Tamoxifen Ctrough | 218 (163–291) |

199 (148–268) |

170 (132–218) |

−9.6% (−26.4 to +11.2) |

0.27 | −24.6% (−33.9 to −14.1) |

<0.01 * |

| Endoxifen AUC0–24h | 745 (576–963) |

716 (574–893) |

596 (495–717) |

−5.7% (−19.6 to +10.7) |

0.39 | −18.4% (−36.1 to +4.3) |

0.09 |

| Endoxifen Ctrough | 30 (23–39) |

31 (25–38) |

25 (20–30) |

−0.3% (−12.8 to +13.9) |

0.96 | −17.2% (−26.1 to −7.3) |

<0.01 * |

| Adverse Event | Tamoxifen Monotherapy N (%) (A) | Tamoxifen with Curcumin N (%) (B) | Tamoxifen with Curcumin and Piperine N (%) (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 2(13) | 1(6) | 1(6) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 1(6) | 3(19) |

| Constipation | 2(13) | 4(25) | 1(6) |

| Fatigue | 2(13) | 3(19) | 3(19) |

| Hot flashes | 3(19) | 5(31) | 4(25) |

| Reflux | 1(6) | 1(6) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 0 | 1(6) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 1(6) | 0 | 1(6) |

| Pain | 4(25) | 0 | 2(13) |

| Rash | 1(6) | 0 | 1(6) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 0 | 0 | 1(6) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1(6) | 1(6) | 1(6) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Many animal and clinical studies supported the use of curcumin to treat different cancer types including BC. Curcumin can be considered for further testing to augment conventional anticancer therapies. However, the low bioavailability of this phytochemical is one of the main problems to be solved before using it as a standard therapeutic agent to treat cancer.

Role of curcumin in regulating p53 in breast cancer: an overview of the mechanism of action

Abstract

p53 is a tumor suppressor gene involved in various cellular mechanisms including DNA repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest. More than 50% of human cancers have a mutated nonfunctional p53. Breast cancer (BC) is one of the main causes of cancer-related deaths among females. p53 mutations in BC are associated with low survival rates and more resistance to the conventional therapies. Thus, targeting p53 activity was suggested as an important strategy in cancer therapy. During the past decades, cancer research was focused on the development of monotargeted anticancer therapies. However, the development of drug resistance by modulation of genes, proteins, and pathways was the main hindrance to the success of such therapies. Curcumin is a natural product, extracted from the roots of Curcuma longa, and possesses various biological effects including anticancer activity. Previous studies proved the ability of curcumin to modulate several signaling pathways and biomolecules in cancer. Safety and cost-effectiveness are additional inevitable advantages of curcumin. This review summarizes the effects of curcumin as a regulator of p53 in BC and the key molecular mechanisms of this regulation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Articles from Breast Cancer : Targets and Therapy are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

Gerelateerde artikelen

- Curcumine en Qingdai, twee Chinese kruidenextracten, verminderen actieve Colitis Ulcerosa in vergelijking met placebo met een respons van 50 tot 90 procent

- Curcumine gecombineerd met PDT - Foto Dynamische Therapie geeft uitstekende resultaten bij verschillende vormen van kanker blijkt uit recent gepubliceerde reviewstudie

- Curcuma extract geeft veel minder bijwerkingen zoals orale mucositis, slikproblemen en huidontstekingen bij patiënten met mond- en keelkanker die chemo plus bestraling kregen in vergelijking met placebo

- Curcumine toegevoegd aan FOLFOX chemotherapie voor darmkankerpatienten stadium IV geeft veel langere mediane overall overleving. 200 dagen versus 502 dagen copy 1

- Intraveneus curcumine in combinatie met chemo (paclitaxel) bij borstkankerpatienten met uitgezaaide borstkanker geeft betere respons (plus 23 procent) en lichamelijk welbevinden in vergelijking met een placebo na 12 weken chemokuren

- Een half jaar dagelijks curcumine (1440 mg/dag) stabiliseert PSA progressie in vergelijking met placebo veel beter (30 vs 10 procent) bij prostaatkankerpatiënten in hormoonvrije periode

- Is kurkuma - curcumine gevaarlijk naast hormoontherapie (Tamoxifen) bij borstkankerpatienten? Onderzoekers van Erasmus MC beweren van wel maar is paniek zaaien voor niets blijkt uit nadere analyse

- Curcumine kan geen geneesmiddel zijn schrijft Henk Timmerman emeritus hoogleraar farmachemie in Medisch Contact n.a.v. reviewstudie The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin

- Welke curcuma extracten zijn het beste in biologische beschikbaarheid en in welke combinaties met reguliere geneesmiddelen moet je voorzichtig zijn met curcuma extracten. Apotheker Han Siem geeft uitleg

- Is beter opneembare curcuma ook effectiever? Niet altijd want andere aspecten spelen ook een rol

- Curcumine extract voorkomt veel beter dan placebo dat leukoplakie - aften uitgroeit tot kwaadaardige tumoren in mond en keel.

- Curcuma - Curcuminoïden supplement (biologisch opneembaar) naast chemo remt ontstekingen en verbetert sterk de kwaliteit van leven van kankerpatiënten in vergelijking met een placebo

- Achtergrond en werking van het voedingssupplement Curcumine - Kurkuma dat bij zo goed als alle kankersoorten en naast chemo en bestraling een bewezen therapeutisch effect heeft

- Kurkuma - curcumine supplementen beschermt vrouwen met borstkanker tegen huidschade - dermatitis - door bestraling met 60 procent verschil

- AMC onderzoekt effect van curcumine - kurkuma vooraf aan PDT - Photo Dynamische Therapie in opdracht van het SNFK

- Kurkuma: Kan curcumin, een belangrijke component van het kruid kurkuma, helpen bij het bestrijden van kanker, en specifiek bij hersentumoren bij kinderen

- Curcuma blijkt een verrassend veelzijdig natuurlijk middel dat goed effect heeft bij veel verschillende kwalen, aldus Selma Timmer, medisch journalist

- Curcumine - kurkuma - geeft bij Multiple Myeloma een positief effect in een behandeling aldus fase II studie.

- Kurkuma - curcumine blijkt uitstekend middel in de bestrijding van kanker.

- Kurkuma - curcumine heeft een sterke anti kankerwerking, een overzicht van belangrijke studies met kurkuma - curcumine

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Is kurkuma - curcumine gevaarlijk naast hormoontherapie (Tamoxifen) bij borstkankerpatienten? Onderzoekers van Erasmus MC beweren van wel maar is paniek zaaien voor niets blijkt uit nadere analyse"