Mocht u kanker-actueel de moeite waard vinden en ons willen ondersteunen om kanker-actueel online te houden dan kunt u ons machtigen voor een periodieke donatie via donaties: https://kanker-actueel.nl/NL/donaties.html of doneer al of niet anoniem op - rekeningnummer NL79 RABO 0372931138 t.n.v. Stichting Gezondheid Actueel in Amersfoort. Onze IBANcode is NL79 RABO 0372 9311 38

Helpt u ons aan 500 donateurs?

16 november 2017: Bron: Nat Rev Clin Oncol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2016 Jun 22.

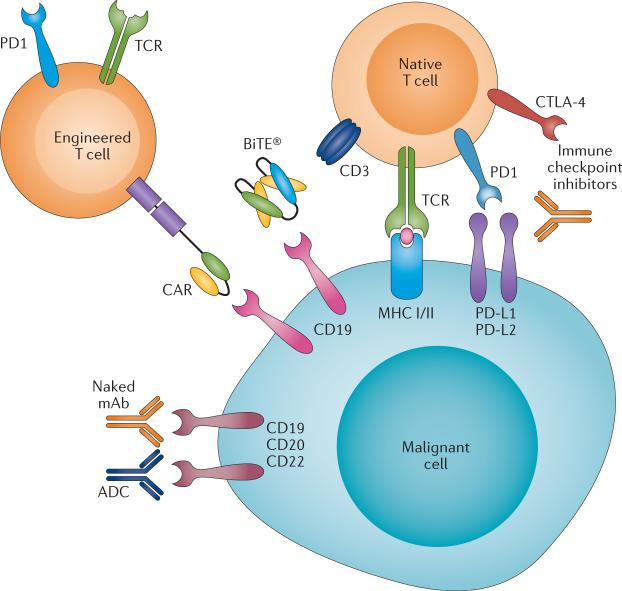

Lymfklierkanker is er in verschillende vormen en sommige vormen ook gerelateerd aan vormen van leukemie. Bv. ziekte van Hodgkin is anders dan Non-Hodgkin maar heeft uiteraard wel verschillende kenmerken. Zo ook zijn er onder vormen van leukemie verschillende vormen, ieder met eigen karakteristieken. Gemeenschappelijk hebben deze vormen van kanker dat ze sterk gerelateerd zijn aan de 'conditie' van het immuunssyteem en de actieve T-cellen. En er wordt al heel lang gezocht naar de beste vorm van immuunstimulerende medicijnen en behandelingen bij deze vormen van kanker met zoals ze dat noemen kwaadaardige lymfoïden.

Zo heeft het zogeheten anti-CD20 monoklonale antilichaam rituximab bij de behandeling van vormen van lymfklierkanker en vormen van leukemie veel succes bij deze vormen van kanker. In feite is rituximab ook een vorm van immuuntherapie. Sinds de goedkeuring door de FDA van rituximab in 1997 zijn er de afgelopen jaren wel ook weer verschillende nieuwe vormen van immuunstimulatie onderzocht die het vermogen om de T-cellen te stimuleren en nog gerichter de kankercellen aan te kunnen vallen. En met succes lijkt het.

Rekening houdend met de veelbelovende resultaten uit de praktijk van deze nieuwe immunotherapiebenaderingen, heeft de FDA onlangs een 'doorbraak'-aanduiding toegekend aan drie nieuwe immuunstimulerende behandelingen met verschillende mechanismen.

Ten eerste is chimere antigeenreceptor (CAR) -T-celtherapie veelbelovend voor de behandeling van een recidief van ALL - acute lymfoblastische leukemie bij volwassenen en kinderen.

Ten tweede is blinatumomab, een zogeheten anti lichaam met bispecifieke T-cel stimulatie (BiTE®), inmiddels goedgekeurd voor de behandeling van volwassenen met Philadelphia-chromosoom-negatieve gerecidiveerde en / of refractaire B-precursor ALL.

Ten derde heeft immuuntherapie met het zogeheten anti-PD medicijn nivolumab, uitstekende resultaten laten zien voor de behandeling van het Hodgkin-lymfoom nadat een recidief optrad na de behandeling met autologe stamceltransplantatie en brentuximab-vedotine.

Er zijn drie studies die recent zijn gepubliceerd die ik onder jullie aandacht wil brengen:

Deze studie: The landscape of new drugs in lymphoma bespreekt alle vormen van medicijnen bij vormen van lymfklierkanker.

Een andere studie is de studie: Clinical applications of genome studies waarin bepaalde biomarkers een grote rol spelen bij de aanpak van lymjfklierkanker en aanverwante vormen van kanker.

En recent is er ook een studie gepubliceerd: Novel immunotherapies in lymphoid malignancies waarin de onderzoekers de achtergrond en ontwikkeling van drie verschillende vormen van immuuntherapie bespreken aan de hand van de literatuur en de wetenschappelijke vooruitgang daarin. M.i. geeft deze studie een uitstekende analyse en maakt het werkingsmechanisme van elke individuele therapie inzichtelijk en begrijpelijk. In de studie bespreken zij ook toekomstige strategieën om deze immunotherapie verder te verbeteren door middel van verbeterde engineering, biomarkerselectie en mechanisme-gebaseerde combinaties van behandelingen. Over deze studie geef ik in dit artikel wat meer informatie.

Het volledige studierapport: Novel immunotherapies in lymphoid malignancies is onderverdeeld in verschillende hoofdstukken. Klik op de kopjes om naar de hoofdstukken te gaan. Ik heb niet altijd een vertaling gemaakt maar u kunt altijd de google translate optie gebruiken rechtsboven elk artikel.

Conclusie uit dit hoofdstukje:

On the basis of promising clinical results, multiple pharmaceutical companies (such as Novartis, Juno Therapeutics, Cellular Biomedicine Group, Bellicum, Celgene/Bluebird, Kite Pharma/Amgen, Cellectis/Servier/Pfizer, Opus Bio, TheraVectys) are developing large-scale clinical-grade production of CAR T cells91. The participation of pharmaceutical companies is critical for success; however, the treatment is unlikely to be standardized in the near future owing to patent issues. Identification of a lead CAR-T-cell construct is unlikely in the absence of head-to-head trials that directly compare each construct and each method in specific disease settings. Results of larger studies of homogenously treated patients across multiple centres with detailed toxicity assessment will be essential in guiding the clinical development of this novel treatment strategy.

Hier een schema van studies met T-car cells. Nummers verwijzen naar referentieliijst onderaan dit artikel

Table 1

Clinical efficacy of second generation CAR-T-cell therapy

| Disease and treating institute | Number of patients | Conditioning therapy | Infused CAR T-cell dose | Response rate | Survival outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | PR (%) | SD (%) | |||||

| ALL | ||||||||

| MSKCC44,48–50 | 22 (16* + 6‡) | CY (1.5–3.0 g/m2) | 1–3 × 106/kg | NA | 91 | NA | NA | Median OS: 9 months |

| UPenn51 | 30* | FLU (30 mg/m2 × 4 days)/CY (500 mg/m2 × 2 days): 13, FLU (30 mg/m2 × 4 days)/CY (300 mg/m2 × 2 days): 2, CY (440 mg/m2 × 2 days)/VP (100 mg/m2 × 2 days): 5, CVAD (CY 300 mg/m2 q12h × 3 days, vincristine 2 mg day 3, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 day 3): 2, CY (300 mg/m2 q12h × 3 days or 1,000 mg/m2 × 1 day): 3, clofarabine 30 mg/m2 × 5 days: 1; VP (150 mg/m2 × 1 day)/Ara-C (300 mg/m2 × 1 day): 1 None: 3 |

0.76–14.96 × 106/kg | NA | 90 | NA | NA | NA |

| NCI52 | 20* | FLU (25 mg/m2 × 3 days)/CY (900 mg/m2 × 1 day) | 1 or 3 × 106/kg | NA | 70 | NA | 15 | RFS: 78.8% at 4.8 months |

| Fred Hutchinson88 | 7‡ | Lymphodepleting chemotherapy | 2 × 105/kg, 2 × 106/kg, or 2 × 107/kg | NA | 71.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| CLL | ||||||||

| UPenn45,60,61 | 14 (3* + 11‡) | FLU (30 mg/m2 × 3 days)/CY (300 mg/m2 × 3 days): 3, pentostatin/CY§: 5, bendamustine§: 6 | 0.14–5.9 × 108 | 57.1 | 21.4 | 35.7 | NA | NA |

| UPenn62 | 23‡ | Lymphodepleting chemotherapy | 5 × 107 or 5 × 108 | 39 | 22 | 17 | NA | NA |

| NCI63 | 4* | FLU (25 mg/m2 × 5 days)/CY (60 mg/kg × 2 days) + i.v. IL-2 following CAR-T-cell infusion | 0.3–3 × 107/kg | 75 | 25 | 50 | 25 | NA |

| NCI64 | 4* | FLU (25 mg/m2 × 5 days)/CY (60 or 120 mg/kg × 2 days) | 1–5 × 106/kg | 100 | 75 | 25 | NA | NA |

| MSKCC44,58 | 10 (8* + 2‡) | None: 4, CY-conditioning (1.5 or 3 g/m2): 4, BR (rituximab 375 mg/m2 × 1 day, bendamustine 90 mg/m2 × 2 days): 2 | 0.4–1.0 × 107/kg | 20 | 10 | 10 | 20 | NA |

| MSKCC59 | 7‡ | PCR∥ × 6 cycles, CY (600 mg/m2) | 3–30 × 106/kg | 57.2 | 14.3 | 42.9 | NR | NA |

| B-NHL | ||||||||

| NCI63 | 4* | FLU (25 mg/m2 × 5 days)/CY (60 mg/kg × 2 days) + i.v. IL-2 following CAR-T cell infusion | 0.3–3 × 107/kg | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | NA |

| NCI64 | 11* | FLU (25 mg/m2 × 5 days)/CY (60 or 120 mg/kg × 2 days) | 1–5 × 106/kg | 88.9 | 55.6 | 33.3 | 11.1 | NA |

| NCI65 | 9‡ | FLU (30 mg/m2 × 3 days)/CY (300 mg/m2 × 3 days) | 1 × 106/kg | 66.7 | 11.1 | 55.6 | 0 | NA |

| MSKCC67 | 6‡ | BEAM conditioning and autologous SCT | 5–10 × 106/kg | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| UPenn66 | 8‡ | EPOCH, CY, bendamustine, FLU/CY§ | 3.7–8.9 × 106/kg (median 5.8 × 106/kg) | 50 | 37.5 | 12.5 | 0 | NA |

| Fred Hutchinson88 | 9‡ | Lymphodepleting chemotherapy | 2 × 105/kg, 2 × 106/kg, or 2 × 107/kg | 66.7 | 11.1 | 55.6 | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphocytic leukaemia; BEAM, BCNU (carmustine) + etoposide + cytarabine + melphalan; B-NHL, B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; CR, complete response; CVAD, cyclophosphamide + vincristine + doxorubicin + dexamethasone; CY, cyclophosphamide; EPOCH, etoposide + vincristine + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + prednisone; FLU, fludarabine; Fred Hutchinson, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; i.v., intravenous; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NA, not applicable; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; RFS, relapse-free survival; SD, stable disease; UPenn, University of Pennsylvania; VP etoposide.

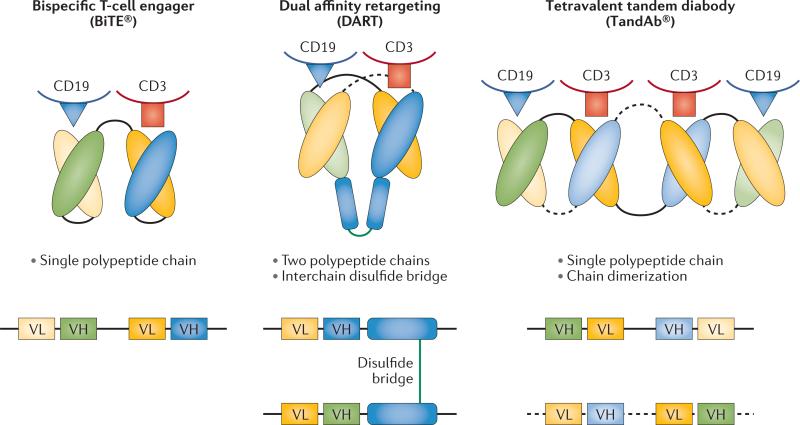

Bispecific antibodies and derivatives

Wat zijn bispecifieke anti bodies?

Bispecifieke antilichamen en aanverwante derivaten zijn ontwikkeld door modulering van bepaalde eiwitten (proteïne-engineering) die de basis vormen van antilichamen om de valentie (mogelijkheid om vedrbindingen aan te gaan) te verhogen, wat de betrokkenheid van het immuunsysteem vergemakkelijkt. De initiële ontwikkeling van bispecifieke antilichamensamenstellingen had te maken met veel problemen die onderzoekers moesten zien te voorkomen, waaronder immunogeniciteit van het product, onvoldoende klinische activiteit en problemen bij grootschalige productie. Nieuwe platforms worden nu ontwikkeld voor de behandeling van vormen van lymfklierkanker en leukemie. (lees verder in studierapport)

(Bispecific antibodies and subsequent derivatives have been developed through protein engineering of the antibody backbone to increase valency, which facilitates engagement of the immune system. The initial development of bispecific-antibody constructs faced many challenges, including immunogenicity of the product, insufficient clinical activity, and difficulties in large-scale production. Novel platforms are being developed for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies.)

Studies met

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors

Hier een schema van studies met anti-PD medicijnen. Nummer erachter correspondeert met literatuurlijst onderaan dit artikel:

Table 3

Clinical efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors

| Drug (manufacturer) and disease | Number of patients | Treatment schedule | Response rate | Median duration of response (range) | Survival outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR (%) | CR (%) | PR (%) | SD (%) | |||||

| Nivolumab (BMS, USA) | ||||||||

| B-NHL145* | 31‡ | 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg week 1, week 4, and every 2 weeks thereafter | 26 | 10 | 16 | 52 | NA | NA |

| DLBCL145* | 11‡ | 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg week 1, week 4, and every 2 weeks thereafter | 36 | 18 | 18 | 27 | 22 weeks (6–77 weeks) | NA |

| Follicular lymphoma145* | 10‡ | 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg week 1, week 4, and every 2 weeks thereafter | 40 | 10 | 30 | 60 | Not reached (27–82 weeks) | NA |

| T-NHL145 | 23‡ | 3 mg/kg week 1, week 4, and every 2 weeks thereafter | 17 | 0 | 17 | 43 | NA | NA |

| Hodgkin lymphoma145,148 | 23§ | 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg week 1 and 4, and every 2 weeks thereafter | 87 | 26 | 61 | 13 | NA | PFS: 86% at 24 weeks OS: median not reached |

| Pembrolizumab (Merck, USA) | ||||||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma150 | 29‡ | 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks | 66 | 21 | 45 | 21 | Not reached (1–185 days) | NA |

| Ipilimumab (BMS, USA) | ||||||||

| B-NHL154 | 18 | 3 mg/kg → 1 mg/kg × 3 doses (or 3 mg/kg × 4 doses in 6 patients) | 11.1 | 5.6 | 5.6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Hodgkin lymphoma (post alio SCT)172 | 14§ | 0.1–3.0 mg/kg | 14.3 | 14.3 | 0 | 14.3 | NA | NA |

We staan aan het begin van een interessant tijdperk van immunotherapeutische behandelingen voor lymfoïde maligniteiten. Veelbelovende resultaten met CAR T-cellen, bispecifieke antilichamen en hun derivaten en anti-PD medicijnen (checkpoint remmers) zijn inmiddels aangetoond, en zonder twijfel zullen vormen van immuuntherapie een van de centrale componenten worden van behandelingsopties bij lymfoïde maligniteiten, vooral bij recideiven of progrssie van de ziekte.

Ondanks het enthousiasme moeten wel nog enkele problemen worden overwonnen, waaronder technische modulering, met name van CAR-T-celtherapieën en bispecifieke antilichamen. Vergeleken met het verbluffende resultaat van zowel CAR-T-celtherapie als bispecifieke antilichamen bij de behandeling van ALL, zijn de resultaten die worden gezien bij patiënten met non-Hodgkin - NHL en Chronische Lymfatische Leukemie - CLL iets minder opvallend maar blijven veelbelovend; deze inconsistentie kan gedeeltelijk te wijten zijn aan de immuunonderdrukkende micro-omgeving geassocieerd met deze tumoren, hoewel verder onderzoek nodig is om dit verschil in werkzaamheid te verklaren.

Naast een verdere verkenning van de werkzaamheid, moeten we in detail het mechanisme van de acties van elke behandelingsmethode begrijpen om elke behandelingsoptie voor individuele patiënten beter te beheren en te volgen. Tot dusverre zijn er geen onderlinge vergelijkingsstudies uitgevoerd, hetgeen vergelijkingen tussen behandelingsmodaliteiten uitsluit. Elk platform heeft zijn eigen sterke en zwakke punten. Het vergelijkbare werkingsmechanisme van blinatumomab en op CD19 gerichte CAR T-cellen vertonen bijvoorbeeld een vergelijkbaar bijwerkingenprofiel. CIV-toediening van blinatumomab is ongemakkelijk, hoewel de korte halfwaardetijd van dit middel voordelig is omdat het een snelle toediening / werking van het geneesmiddel mogelijk maakt om de toxiciteit te minimaliseren.

De bij patiënten aanwezigheid en vermeerdering van CAR T-cellen resulteert in een variabele dosis-effect relatie tussen de verschillende patiënten; de levensduur van de T-cellen kan echter zorgen voor langdurige ziektebestrijding. Anti-PD-1-antilichamen hebben een opmerkelijke werkzaamheid tegen Hodgkin Lymfomen getoond, maar er zijn combinaties van behandelingen nodig om de CR - Complete Remissie percentages te verbeteren. De resultaten van lopende en toekomstige studies zullen ons in staat stellen om het verschil in gebruik van deze behandelingen te begrijpen als een enkele of een gecombineerde behandeling die de prognose van patiënten verbetert.

Het volledige studierapport: Novel immunotherapies in lymphoid malignancies isgratis in te zien. Hieronder het abstract met uitgebreide referentielijst.

We are entering an exciting era of immunotherapies for lymphoid malignancies. Promising results with CAR T cells, bispecific antibodies and their derivatives, and immune-checkpoint blockade have been demonstrated, and without doubt, immunotherapies will become one of the central components of treatment strategies in lymphoid malignancies, especially in the relapsed and/or refractory setting.

Novel immunotherapies in lymphoid malignancies

In this Review, we describe the most promising agents in clinical development for the treatment of lymphoma, and provide expert opinion on new strategies that might enable more streamlined drug development. We also address new approaches for patient selection and for incorporating new end points into clinical trials.

The landscape of new drugs in lymphoma

Gerelateerde artikelen

- Tafasitamab - Monjuvi in combinatie met lenalidomide - Revlimid en R-CHOP geeft betere ziekteprogressievrije overleving in vergelijking met alleen R-CHOP bij patiënten met lymfklierkanker type diffuus grootcellig B-cellymfoom (Non-Hodgkin)

- loncastuximab tesirine en glofitamab combinatie geeft uitstekende resultaten met 89 procent ziektecontrole en 77 procent complete remissies bij patienten met uitgezaaide gevorderde B-cel non-Hodgkin-lymfoom

- CAR-T celtherapie - Axicabtagene ciloleucel geeft veel betere ziektevrije overleving in vergelijking met de standaardbehandeling van tweedelijnstherapie bij patiënten met recidief, ziekteprogressie van lymfklierkanker type diffuus grootcellig B-cellymfoom

- Immuuntherapie met nivolumab naast standaard chemo als eerstelijns behandeling zorgt voor betere resultaten en minder bijwerkingen bij patienten met klassieke ziekte van Hodgkin stadium III en IV in vergelijking met brentuximab vedotin

- Immuuntherapie met CAR-T celtherapie (isocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel)) geeft meer complete remissies en betere overall overleving dan chemo + stamceltransplantatie als tweedelijnsbehandeling bij patienten met grootcellig B-cel lymfoom

- Autologe stamceltransplantatie plus anti-CD30 CAR-T celtherapie geeft 5 duurzame complete remissies bij 6 deelnemende patienten met lymfklierkanker die al paar keer een recidief hadden gehad ondanks chemokuren.

- Autologe stamceltransplantatie na immuuntherapie met anti-PD medicijnen geeft zeer goede resultaten voor gevorderde lymfklierkanker - Hodgkin lymfoom zelfs bij zwaar voorbehandelde patiënten

- Glofitamab, een antibody medicijn, alleen en in combinatie met obinutuzumab geeft nog goede respons (36 procdent) bij zwaar voorbehandelde patienten met recidief of refractair B-cel non-hodgkin-lymfoom.

- Mosunetuzumab, een bispecifiek monoklonaal antilichaam, geeft uitstekende resultaten (CR bij 60 procent) bij patienten met een Folliculair lymfoom waarbij eerdere behandelingen faalden.

- Pembrolizumab geeft langdurige complete en gedeeltelijke remissies (4 jaar en langer) bij zwaar voorbehandelde patiënten met klassiek Hodgkin-lymfoom na falen van brentuximab vedotin

- Immuuntherapie met Nivolumab solo of naast chemo (N-AVD) gevolgd door radiotherapie bij patiënten met hoog risico van lymfklierkanker als eerstelijns behandeling geeft uitstekende resultaten op korte termijn

- Bendamustine plus Rituximab gevolgd door behandelingen met 90-Yttrium plus 4x Ibritumomab Tiuxetan voor onbehandelde Folliculaire Lymfomen geeft betere overall overleving en langere duurzame ziektevrije tijd copy 1

- Immuuntherapie met Camrelizumab, een anti-PD medicijn geeft hele goede resultaten met complete en gedeeltelijke remissies bij patienten met recidief of ziekteprogressie van klassieke lymfklierkanker

- Immuuntherapie met gemanipuleerde T-cellen - CAR-T celtherapie ( tisagenlecleucel ) geeft spectaculair goede resultaten bij patienten met gevorderde lymfklierkanker - non-Hodgkin (B-lymfomen) copy 1

- Lenalidomide naast rituximab verbetert mediane progressievrije overleving met 25 maanden (39 vs 14 maanden) bij patienten met recidief van indolente lymfomen - lymfklierkanker, in vergelijking met alleen rituximab

- Ivo Visser uitbehandeld voor zeldzame vorm van lymfklierkanker komt alsnog in total remissie (kankervrij) met T-CAR cel immuuntherapie

- Immuuntherapie met extra gemoduleerde T-car cells geeft bij zwaar voorbehandelde lymfklierkanker non-Hodgkin alsnog uitstekende resultaten met 33 procent complete remissies

- Lymfklierkanker en leukemie kennen verschillende vormen en stadia. Hier een recente studie van de belangrijkste behandelingsopties, vooral met vormen van immuuntherapie

- Obinutuzumab aanvullend op standaard chemokuren, verlengt ziektevrije overall overleving (plus 34 procent) van indolente Non Hodgkin Lymphomen stadium III / IV in vergelijking met standaard chemo plus Rituximab.

- Pembrolizumab, immuuntherapie met een anti-PD medicijn, geeft uitstekende resultaten bij recidief of progressie van voorbehandelde patienten met lymfklierkanker, non-Hodgkin

- Pembrolizumab geeft zeer goede resultaten (65 procent respons) bij klassieke lymfklierkanker (Hodgkin) bij zwaar voorbehandelde patienten en na falen van o.a. brentuximab plus vedotin

- Nivolumab - Opdivo geeft extreem goede resultaten - 87 procent respons - bij zwaar voorbehandelde patienten met lymfklierkanker

- Genentest met 7 nieuwe genmutaties voorspelt of immuuntherapie met Rituximab aanvullend op CHOP kuren zal slagen of falen bij non-Hodgkin - folluculaire lymfoma copy 1

- Brentuximab Vedotin (SGN-35) blijkt succesvolle aanpak voor gevorderde lymfklierkanker, non-hodgkin lymfomen met CD30 positieve expressie.

- BiovaxID, een vaccin, geeft significant langere ziektevrije tijd bij lymfklierkanker (non-Hodgkin) blijkt uit fase III studie.

- Immuuntherapie bij lymfklierkanker: BiovaxID(TM), een Vaccinatie - immuuntherapie bij non-Hodgkin geeft goede resultaten uit fase I en II en fase III trials.

- Immuuntherapie bij lymfklierkanker: Non-Hodgkin en vaccinatie met BiovaxID is succesvolle en veelbelovende aanpak.

- Pentostatin - Nipent lijkt effectief middel om afstoting tegen te gaan bij immuuntherapie en stamceltransplanties bij verschillende vormen van kanker waaronder lymfklierkanker en leukemie

- Immuuntherapie bij lymfklierkanker: een overzicht van recente ontwikkelingen

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Lymfklierkanker en leukemie kennen verschillende vormen en stadia. Hier een recente studie van de belangrijkste behandelingsopties, vooral met vormen van immuuntherapie"