Mocht u kanker-actueel de moeite waard vinden en ons willen ondersteunen om kanker-actueel online te houden dan kunt u ons machtigen voor een periodieke donatie via donaties: https://kanker-actueel.nl/NL/donaties.html of doneer al of niet anoniem op - rekeningnummer NL79 RABO 0372931138 t.n.v. Stichting Gezondheid Actueel in Amersfoort. Onze IBANcode is NL79 RABO 0372 9311 38

Elk bedrag is welkom. En we zijn een ANBI instelling dus uw donatie of gift is in principe aftrekbaar voor de belasting.

En als donateur kunt u ook korting krijgen bij verschillende bedrijven:

22 mei 2016: Lees naast de gerelateerde artikelen o.a. ook dit artikel:

22 mei 2016: Bron: JAMA Oncol. Published online May 19, 2016.

Met een verandering van leefstijl, waarin een hoofdrol voor bewegen, alcohol consumptie, roken en obesitas, zou 20 tot 50 procent van de meeste vormen van kanker te voorkomen zijn. Voor longkanker en darmkanker stijgen die percentages zelfs tot 70 procent. Dit is natuurlijk al veel langer bekend en er wordt ook wel veel aandacht gegeven aan preventie middels leefstijladviezen. Maar is maar weer eens bevestigd nu in een meta analyse van de Nurses’ Health Study en de Health Professionals Follow-up Study,

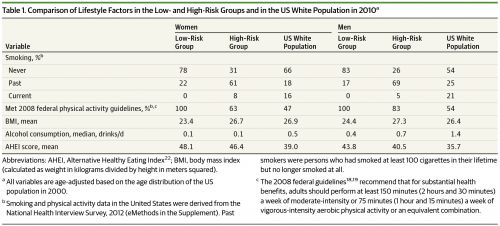

Een gezonde leefstijl werd gedefinieerd als:

- Nooit gerookt hebbende of in ieder geval niet de laatste 5 jaar

- Geen of weinig alcohol consumptie (≤1 alcohol bevattend drankje/per dag voor vrouwen, ≤2 alcohol bevattende dankjes/per dag voor mannen),

- BMI - Body Mass Index van minstens 18.5 maar in ieder geval lager dan 27.5,

- Wekelijks een aerobische of een intensieve fysieke activiteit (echt sporten dus) van tenminste 75 minuten of 150 minuten van bewegen maar mag ook minder intensief en kan dus ook een flinke wandeling zijn.

Deelnemers aan de studie die voldeden aan al die vier criteria vormen de lage risicogroep. Alle andere deelnemers vormen de hoog risciogroep gerelateerd aan hun scores in die vier categorien.

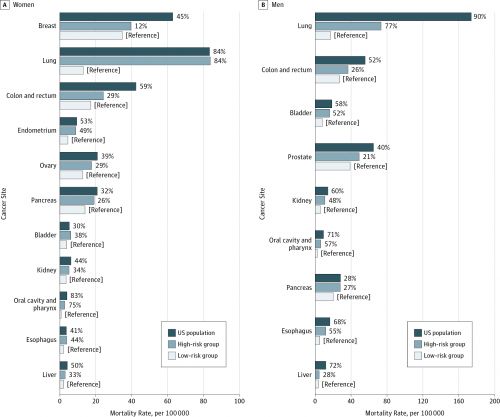

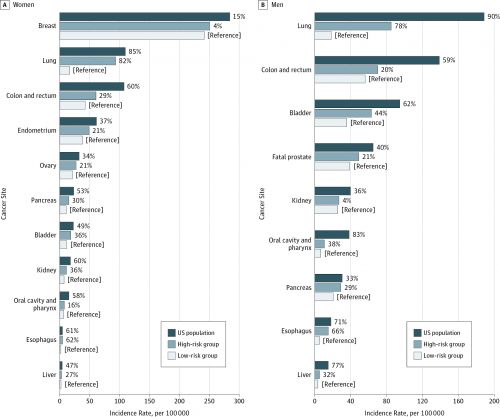

De onderzoekers berekenden het populatie-toerekenbare risico (population-attributable risk - PAR) door de vergelijking te maken van nieuwe diagnoses van kanker en overlijden aan kanker in zijn algemeenheid en per vorm van meest voorkomende vormen van kanker tussen de laag risico en hoog riscio groepen. Verder vergeleken de onderzoekers de resultaten met de gegevens uit de nationale registratie van kanker bij de Amerikaanse bevolking.

Totaal 89 571 vrouwen en 46 339 mannen van de twee studies werden opgenomen in deze studie: 16 531 vrouwen en 11 731 mannen voldeden aan een gezonde leefstijl (laag risico groep), en de overblijvende 73 040 vrouwen en 34 608 mannen bouwden de hoog risico groep op.

Het populatie-toerekenbare risico (PAR) voor de diagnose van nieuwe kanker en overlijden aan kanker in het algemeen zijn de cijfers 25% (nieuwe diagnose) en 48% (overlijden) bij vrouwen en 33% en 44% bij mannen respectievelijk.

Voor individuele vormen van kanker was het populatie-toerekenbare risico (PAR) voor vrouwen en mannen waren respectievelijk 82% en 78% voor longkanker, 29% en 20% voor darmkanker en rectumkanker, 30% en 29% voor alvleesklierkanker en 36% en 44% voor blaaskanker.

Het toerekenbare-risico (PAR) waren 4% (diagnose) en 12% (overlijden) voor borstkanker en 21% voor fatale agressieve prostaatkanker. Substantieel hogere cijfers werden genoteerd wanneer de Par werd vergeleken met de Amerikaanse bevolking. Bv. de PAR lag op 41% bij vrouwen en 63% bij mannen voor kanker in het algemeen en 60% (bij vrouwen) en 59% (bij mannen) voor vormen van darmkanker.

De onderzoekers concluderen dan ook dat preventie van kanker middels lijfstijl veranderingen hoge prioritiet moet krijgen in de voorlichting aan de bevolking. Maar ja hoe lang weten we dat nu al niet?

Het volledige studierapport: Preventable Incidence and Mortality of Carcinoma Associated With Lifestyle Factors Among White Adults in the United States is gratis in te zien of te downloaden. Met duidelijke grafieken en goede beschrijvingen als u goed Engels leest en begrijpt.

Hieronder het abstract van de studie met referentielijst.

A substantial cancer burden may be prevented through lifestyle modification. Primary prevention should remain a priority for cancer control.

Preventable Incidence and Mortality of Carcinoma Associated With Lifestyle Factors Among White Adults in the United States FREE ONLINE FIRST

ABSTRACT

Importance Lifestyle factors are important for cancer development. However, a recent study has been interpreted to suggest that random mutations during stem cell divisions are the major contributor to human cancer.

Objective To estimate the proportion of cases and deaths of carcinoma (all cancers except skin, brain, lymphatic, hematologic, and nonfatal prostate malignancies) among whites in the United States that can be potentially prevented by lifestyle modification.

Design, Setting, and Participants This prospective cohort study analyzes cancer and lifestyle data from the Nurses’ Health Study, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and US national cancer statistics to evaluate associations between lifestyle and cancer incidence and mortality.

Exposures A healthy lifestyle pattern was defined as never or past smoking (pack-years <5), no or moderate alcohol drinking (≤1 drink/d for women, ≤2 drinks/d for men), BMI of at least 18.5 but lower than 27.5, and weekly aerobic physical activity of at least 75 vigorous-intensity or 150 moderate-intensity minutes. Participants meeting all 4 of these criteria made up the low-risk group; all others, the high-risk group.

Main Outcomes and Measures We calculated the population-attributable risk (PAR) by comparing incidence and mortality of total and major individual carcinomas between the low- and high-risk groups. We further assessed the PAR at the national scale by comparing the low-risk group with the US population.

Results A total of 89 571 women and 46 339 men from 2 cohorts were included in the study: 16 531 women and 11 731 men had a healthy lifestyle pattern (low-risk group), and the remaining 73 040 women and 34 608 men made up the high-risk group. Within the 2 cohorts, the PARs for incidence and mortality of total carcinoma were 25% and 48% in women, and 33% and 44% in men, respectively. For individual cancers, the respective PARs in women and men were 82% and 78% for lung, 29% and 20% for colon and rectum, 30% and 29% for pancreas, and 36% and 44% for bladder. Similar estimates were obtained for mortality. The PARs were 4% and 12% for breast cancer incidence and mortality, and 21% for fatal prostate cancer. Substantially higher PARs were obtained when the low-risk group was compared with the US population. For example, the PARs in women and men were 41% and 63% for incidence of total carcinoma, and 60% and 59% for colorectal cancer, respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance A substantial cancer burden may be prevented through lifestyle modification. Primary prevention should remain a priority for cancer control.

References:

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed

PubMed

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

PubMed | Link to Article

Gerelateerde artikelen

- Ouderen (60+) die zich zowel fysiek als mentaal niet goed voelen kunnen binnen drie jaar dit verbeteren door aanpassingen in hun leefstijl

- Leefstijlaanbeveling neurologie om dagelijks te kunnen oefenen staat op landelijke MSZ-implementatieagenda en ziekenhuizen moeten dit binnen twee jaar ingevoerd hebben copy 1

- Leefstijl aanpassingen kan ontstaan van kanker en sterfgevallen door kanker onder volwassenen in de VS verminderen met respectievelijk 40 en 50 procent. Blijkt uit nieuwe studie van de American Cancer Society.

- Leefstijl verandering, niet roken en zonbescherming kan elk jaar 40.000 kankerpatienten voorkomen blijkt uit nieuw Nederlands onderzoek

- Leefstijl en voeding heeft ook invloed op een erectiestoornis. Wie gezond eet en drinkt en regelmatig beweegt kan erectiestoornissen vaak voorkomen

- Kanker is voor de helft te voorkomen door verandering van leefstijl, waarbij alcohol en roken en overgewicht de grootste boosdoeners zijn blijkt uit berekening van de Global Burden of Diseases

- FODMAP-dieet stimulatie via een APP geeft betere resultaten dan de standaard medicijnen bij patienten met eerste diagnose van PDS - Prikkelbare Darm Syndroom

- Gezonde leefstijl zonder roken, met veel beweging, meer groenten enz. voorkomt vaker ziek worden en verlengt levensduur met 6 jaar blijkt uit Nederlandse studie onder 9000 mensen van middelbare leeftijd.

- Gezonde leefstijl met volkoren producten, dagelijks bewegen en weinig rood en bewerkt vlees kan darmkanker voorkomen tot wel 45 procent

- Leefstijl en omgevingsfactoren zoals voedingspatroon, beweging, stress en luchtvervuiling spelen veel grotere rol - 70 tot 80 procent - in het ontstaan van meeste vormen van kanker dan pech in de vorm van erfelijke afwijkingen

- Gezond leven en eten - drinken programma op basisschool en middelbare school heeft langdurige positieve invloed op verminderen en voorkomen van obesitas.

- Gezonde voeding en leefstijl kan risico op borstkanker met ruim 50% verkleinen, maar ook andere vormen van kanker zijn gevoelig voor leefstijl en voedingspatroon. Aldus nieuwe analyse van grootschalig rapport van het Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds - WCRF-n

- Wereldwijd onderzoek bewijst: risico op kanker is met goede voeding te verlagen

- Gezonde leefstijl met een evenwichtig voedingspatroon vermindert het risico op vroegtijdig overlijden aan kanker met 20 procent, risico op ook andere ziekten erbij met 34 procent

- Gezonde Leefstijl met niet roken, gezonde voeding, minder alcohol, bestrijding infecties en meer bewegen kan overlijden aan kanker met een derde verminderen blijkt uit groot Australisch bevolkingsonderzoek.

- Milieuvervuiling: grote Japanse studie bewijst significant hogere sterfte en optreden van ernstige ziektes zoals kanker door fijn stof. RIVM geeft overzicht van fijn stof emissie in onze gezondheid

- Leefstijlveranderingen in voeding en bewegen zou 20 tot 50 procent van de meeste vormen van kanker en overlijden daaraan kunnen voorkomen. Darmkanker zelfs tot 70 procent.

- Leefstijl en voeding in eerste twintig jaar van een mensenleven lijkt bepalend voor risico op krijgen van kanker toont grote Zweedse studie.

Plaats een reactie ...

Reageer op "Leefstijlveranderingen in voeding en bewegen zou 20 tot 50 procent van de meeste vormen van kanker en overlijden daaraan kunnen voorkomen. Darmkanker zelfs tot 70 procent."