22 november 2017: Bron: Oncotarget. 2017; 8:67269-67286.

Onderstaande is een vrije vertaling met ook eigen teovoegingen uit de studie zelf van een artikel in Science Daily over deze studie.

Kankerstamcellen, die de groei van nieuwe en bestaande tumoren voeden, kunnen worden uitgeschakeld door een behandelingscombinatie van eerst antibiotica gevolgd door vitamine C. Dat stellen onderzoekers van de Universiteit van Salford, naar aanleiding van resultaten uit hun experimenteel onderzoek.

Het antibioticum, Doxycycline, gevolgd door enkele doses ascorbinezuur (vitamine C), was verrassend effectief bij het doden van de kankerstamcellen in een experimenteel onderzoek. Of zoals de onderzoekers zeggen: "in bokstermen zou dit vergelijkbaar zijn met een combinatie van twee klappen die snel achter elkaar worden afgeleverd; een stoot van de linkerhand, gevolgd door een knockout met de rechter."

De onderzoekers zeggen dat hun methode een nieuwe behandelingsoptie biedt om te voorkomen dat kankercellen resistent worden tegen bepaalde kankerbehandelingen (chemo) en hoe combinaties van behandelingen kunnen worden ontwikkeld om resistentie tegen bepaalde geneesmiddelen (chemo) te overwinnen.

Professor Michael Lisanti, die de studie ontwierp, legt uit: "We weten nu dat een deel van de kankercellen ontsnappen aan chemotherapie en resistentie tegen geneesmiddelen ontwikkelen, we hebben deze nieuwe behandelingscombinaties opgezet om uit te vinden hoe ze het doen.

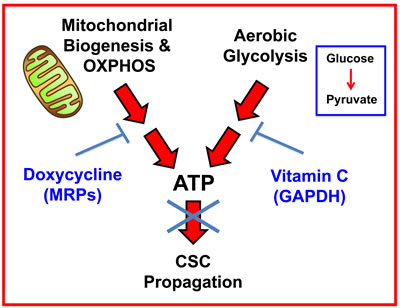

In hun studierapport staat hun aanpak geïllustreerd in veel grafieken, maar is voor leken niet interessant. Hier wel de strategie die de onderzoekers hebben toegepast. Eerst de kankerstamcellen verzwakken en uithongeren met doxycycline en daarna met vitamine C de dodelijk klap uitdelen :

Figure 12: Vitamin C and Doxycycline: A synthetic lethal combination therapy for eradicating CSCs. Note that both OXPHOS and the glycolytic pathway jointly contribute to ATP production. Doxycycline inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS, by acting via mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs); Vitamin C inhibits glycolytic metabolism by targeting and inhibiting the enzyme GAPDH. Therefore, their use together, as a sequential drug combination, will more severely target cell metabolism and energy production, thereby preventing or blocking the propagation of CSCs.

De onderzoekers in Salford hebben onderstaande combinaties uitgeprobeerd maar wel met altijd doxycycline als eerste om de kankerstamcellen te verzwakken / uit te hongeren:

Figure 9: Metabolic inhibitors successfully employed for the eradication of DoxyR CSCs. Briefly, a list of small molecules that we successfully used in conjunction with Doxycycline is shown. These include 9 known inhibitors of OXPHOS, glycolysis and autophagy. Two natural products (Vitamin C and Berberine), six clinically-approved drugs (Atovaquone, Chloroquine, Irinotecan, Sorafenib, Niclosamide, and Stiripentol) and one experimental drug (2-DG), are all highlighted.

"We vermoedden dat het antwoord ligt in het feit dat bepaalde kankercellen - die we metabolisch flexibel noemen - in staat zijn om van brandstofbron te veranderen, dus wanneer de behandeling met chemo de beschikbaarheid van een bepaalde voedingsstof vermindert, kunnen de flexibele kankercellen zichzelf voeden met een alternatieve energiebron.", aldus Professor Michael Lisanti

Deze nieuwe combinatiebehandeling voorkomt dat kankercellen hun dieet veranderen (metabolisch inflexibel) en zal de kankerstamcellen effectief uithongeren door te voorkomen dat ze andere beschikbare soorten biobrandstoffen gaan gebruiken.

De onderzoekers van het Biomedical Research Center van de Universiteit van Salford voegde Doxycycline toe in steeds hogere doses gedurende een periode van drie maanden om metabole inflexibiliteit te creeëren.

Het doel was om de kankercellen wel levend te laten, maar deze proberen te verzwakken en uit te putten zodat ze veel kwetsbaarder zouden zijn voor uithongering, door een tweede zogeheten metabole "punch".

Als eerste remden de onderzoekers de mitochondriën in de tumorcel, door de kankercellen alleen te voeden met glucose als brandstofbron; daarna namen ze hun glucose weg en doodden ze de kankercellen effectief met vitamine C.

Figure 10: Glycolysis inhibitors reduce mammosphere formation in MCF7 DoxyR cells. Evaluation of mammosphere formation in MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells cultured in low attachment plates and treated with Vehicle or increasing concentrations of the glycoysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-glucose (2 DG) (10 mM to 20 mM) for 5 days before counting A. Mammosphere formation is inhibited in MCF7 DoxyR cells cultured in low attachment plates and treated with increasing concentrations of the glycoysis inhibitor Ascorbic Acid (100 µM to 500 µM) for 5 days before counting B. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. (***) p < 0.001.

"In dit scenario gedraagt vitamine C zich als een remmer van glycolyse, wat de energieproductie in de mitochondriën, de" krachtcentrale "van de cel, voedt, verklaart co-auteur Dr Federica Sotgia.

Het Salford-team toonde onlangs aan dat vitamine C tot tien keer effectiever is in het tegenhouden van de groei van kankercellen dan farmaceutische producten zoals 2-DG, maar ze zeggen dat wanneer vitamine C wordt gecombineerd met een antibioticum, het tot tien keer effectiever wordt, waardoor het bijna 100 keer effectiever is dan 2-DG.

Aangezien Doxycycline en vitamine C beide niet-toxisch zijn, kan dit de mogelijke bijwerkingen van een antikankertherapie (chemo) drastisch verminderen. gezien Doxycycline en vitamine C beide niet-toxisch zijn, kan dit de mogelijke bijwerkingen van een antikankertherapie (chemo) drastisch verminderen.

Het team van Salford onderzocht ook acht andere medicijnen die als een "tweede klap" na het antibioticumgebruik konden worden gebruikt, waaronder berberine (een natuurlijk product) - en een aantal goedkope niet-toxische door de FDA goedgekeurde geneesmiddelen.

Professor Lisanti voegde hieraan toe: "Dit is verder bewijs dat vitamine C en andere niet-toxische stoffen een rol kunnen spelen in de strijd tegen kanker. "Onze resultaten geven aan dat het een veelbelovend middel is voor klinische studies en een aanvulling op meer conventionele therapieën, om een tumorrecidief, verdere ziekteprogressie en uitzaaiingen te voorkomen."

Het is een interessante studie en het volledige studieverslag: Vitamin C and Doxycycline: A synthetic lethal combination therapy targeting metabolic flexibility in cancer stem cells (CSCs) met gedetailleerd uitgelegd hoe zij in het werk zijn gegaan is gratis in te zien.

Hier het abstract met uitgebreide originele conclusie

Vitamin C and antibiotics: A new one-two 'punch' for knocking-out cancer stem cells.

Journal Reference:

- Ernestina Marianna De Francesco, Gloria Bonuccelli, Marcello Maggiolini, Federica Sotgia, Michael P. Lisanti. Vitamin C and Doxycycline: A synthetic lethal combination therapy targeting metabolic flexibility in cancer stem cells (CSCs). Oncotarget, 2015; DOI: 10.18632/oncotarget.18428

Metrics: PDF 2077 views | HTML 14065 views ?

Ernestina Marianna De Francesco1,2, Gloria Bonuccelli3, Marcello Maggiolini1, Federica Sotgia3 and Michael P. Lisanti3

1 Department of Pharmacy, Health and Nutritional Sciences, University of Calabria, Rende, Italy

2 The Paterson Institute, University of Manchester, Withington, United Kingdom

3 Translational Medicine, School of Environment and Life Sciences, Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), University of Salford, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom

Correspondenc to:

Michael P. Lisanti, email: michaelp.lisanti@gmail.com

Federica Sotgia, email: fsotgia@gmail.com

Keywords: cancer stem-like cells (CSCs), doxycycline, vitamin C, mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial DNA (mt-DNA)

Received: May 05, 2017 Accepted: May 17, 2017 Published: June 09, 2017

Abstract

Here, we developed a new synthetic lethal strategy for further optimizing the eradication of cancer stem cells (CSCs). Briefly, we show that chronic treatment with the FDA-approved antibiotic Doxycycline effectively reduces cellular respiration, by targeting mitochondrial protein translation. The expression of four mitochondrial DNA encoded proteins (MT-ND3, MT-CO2, MT-ATP6 and MT-ATP8) is suppressed, by up to 35-fold. This high selection pressure metabolically synchronizes the surviving cancer cell sub-population towards a predominantly glycolytic phenotype, resulting in metabolic inflexibility. We directly validated this Doxycycline-induced glycolytic phenotype, by using metabolic flux analysis and label-free unbiased proteomics.

Next, we identified two natural products (Vitamin C and Berberine) and six clinically-approved drugs, for metabolically targeting the Doxycycline-resistant CSC population (Atovaquone, Irinotecan, Sorafenib, Niclosamide, Chloroquine, and Stiripentol). This new combination strategy allows for the more efficacious eradication of CSCs with Doxycycline, and provides a simple pragmatic solution to the possible development of Doxycycline-resistance in cancer cells. In summary, we propose the combined use of i) Doxycycline (Hit-1: targeting mitochondria) and ii) Vitamin C (Hit-2: targeting glycolysis), which represents a new synthetic-lethal metabolic strategy for eradicating CSCs.

This type of metabolic Achilles’ heel will allow us and others to more effectively “starve” the CSC population.

Conclusions

Numerous functional studies have now directly shown that mitochondria are an important new therapeutic target in cancer cells [3, 5, 8-21, 40-53]. Since Doxycycline, an FDA-approved antibiotic, behaves as an inhibitor of mitochondrial protein translation, it may have therapeutic value in the specific targeting of mitochondria in cancer cells. However, in this paper, we have identified a novel metabolic mechanism by which CSCs successfully escape from the anti-mitochondrial effects of Doxycycline, by assuming a purely glycolytic phenotype. Therefore, DoxyR CSCs are then more susceptible to other metabolic perturbations, because of their metabolic inflexibility, allowing for their eradication with natural products and other FDA-approved drugs. Thus, understanding the metabolic basis of Doxycycline-resistance has ultimately helped us to develop a new synthetic lethal strategy, for more effectively targeting CSCs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Doxycycline, Ascorbic Acid, 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), Irinotecan, Berberine Chloride, Niclosamide, Chloroquine diphosphate, Stiripentol and Atovaquone were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Sorafenib was obtained from Generon. All compounds were dissolved in DMSO, except Ascorbic Acid, 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) and Chloroquine diphosphate, which were dissolved in cell culture medium.

Cell cultures

MCF7 breast cancer cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM (Sigma Aldrich). MCF-7 cells resistant to Doxycycline (MCF7 DoxyR) were selected by a stepwise exposure to increasing concentration of Doxycycline. In particular, wild type MCF7 cells were initially exposed to 12.5 µM Doxycycline and the dose gradually increased to 50 µM over a 3-month period. The population of resistant cells, named MCF7 DoxyR, was selected after 3 weeks of treatment with 12.5 µM Doxycycline, followed by 3 weeks of treatment with 25 µM Doxycycline. MCF7 DoxyR cells were routinely maintained in regular medium supplemented with 25 µM Doxycycline.

Mammosphere formation

A single cell suspension of MCF7 or MCF7 DoxyR cells was prepared using enzymatic (1x Trypsin-EDTA, Sigma Aldrich), and manual disaggregation (25 gauge needle) [54]. Cells were then plated at a density of 500 cells/cm2 in mammosphere medium (DMEM-F12/ B27 / 20-ng/ml EGF/PenStrep) in nonadherent conditions, in culture dishes coated with (2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate) (poly-HEMA, Sigma), in the presence of treatments, were required. Cells were grown for 5 days and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C at an atmospheric pressure in 5% (v/v) carbon dioxide/air. After 5 days for culture, spheres > 50 μm were counted using an eye piece graticule, and the percentage of cells plated which formed spheres was calculated and is referred to as percentage mammosphere formation. Mammosphere assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times independently.

Evaluation of mitochondrial mass and function

To measure mitochondrial mass by FACS analysis, cells were stained with MitoTracker Deep Red (Life Technologies), which localizes to mitochondria regardless of mitochondrial membrane potential. Cells were incubated with pre-warmed MitoTracker staining solution (diluted in PBS/CM to a final concentration of 10 nM) for 30-60 min at 37 °C. All subsequent steps were performed in the dark. Cells were washed in PBS, harvested, re-suspended in 300 μL of PBS and then analyzed by flow cytometry (Fortessa, BD Bioscience). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software. Extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) and real-time oxygen consumption rates (OCR) for MCF7 cells were determined using the Seahorse Extracellular Flux (XFe-96) analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) [15]. Briefly, 15,000 MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells per well were seeded into XFe-96 well cell culture plates for 24h. Then, cells were washed in pre-warmed XF assay media (or for OCR measurement, XF assay media supplemented with 10mM glucose, 1mM Pyruvate, 2mM L-glutamine and adjusted at 7.4 pH). Cells were then maintained in 175 µL/well of XF assay media at 37C, in a non-CO2 incubator for 1 hour. During the incubation time, 5 µL of 80mM glucose, 9 µM oligomycin, and 1 M 2-deoxyglucose (for ECAR measurement) or 10µM oligomycin, 9 µM FCCP, 10 µM Rotenone, 10 µM antimycin A (for OCR measurement), were loaded in XF assay media into the injection ports in the XFe-96 sensor cartridge. Data set was analyzed by XFe-96 software after the measurements were normalized by protein content (SRB). All experiments were performed three times independently.

ALDEFLUOR assay and separation of the ALDH positive population

ALDH activity was assessed by FACS analysis (Fortessa, BD Bioscence) in MCF7 cells and MCF7 DoxyR cells. The ALDEFLUOR kit (StemCell Technologies) was used to isolate the population with high ALDH enzymatic activity. Briefly, 1 × 105 MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells were incubated in 1ml ALDEFLUOR assay buffer containing ALDH substrate (5 μl/ml) for 40 minutes at 37°C. In each experiment, a sample of cells was stained under identical conditions with 30 μM of diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), a specific ALDH inhibitor, as a negative control. The ALDEFLUOR-positive population was established in according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was evaluated in 3 × 104 cells. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Anoikis assay

MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells were seeded on low-attachment plates to enrich for the CSC population [54]. Under these conditions, the non-CSC population undergoes anoikis (a form of apoptosis induced by a lack of cell-substrate attachment) and CSCs are believed to survive. The surviving CSC fraction was analyzed by FACS analysis. Briefly, 1 x 105 MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR monolayer cells were seeded for 48h in 6-well plates. Then, cells were trypsinized and seeded in low-attachment plates in mammosphere media. After 10h, cells were spun down and incubated with CD24 (IOTest CD24-PE, Beckman Coulter) and CD44 (APC mouse Anti-Human CD44, BD Pharmingen) antibodies for 15 minutes on ice. Cells were rinsed twice and incubated with LIVE/DEAD dye (Fixable Dead Violet reactive dye; Life Technologies) for 10 minutes. Samples were then analyzed by FACS (Fortessa, BD Bioscence). Only the live population, as identified by the LIVE/DEAD dye staining, was analyzed for CD24/CD44 expression. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Label-free semi-quantitative proteomics analysis

Cell lysates were prepared for trypsin digestion by sequential reduction of disulphide bonds with TCEP and alkylation with MMTS. Then, the peptides were extracted and prepared for LC-MS/MS. All LC-MS/MS analyses were performed on an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) coupled to an Ultimate 3000 RSLC nano system (Thermo Scientific, formerly Dionex, The Netherlands). Xcalibur raw data files acquired on the LTQ-Orbitrap XL were directly imported into Progenesis LCMS software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, formerly Non-linear dynamics, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) for peak detection and alignment. Data were analyzed using the Mascot search engine. Five technical replicates were analyzed for each sample type [8, 12].

Immuno-blot analysis

MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells protein lysates were electrophoresed through a reducing SDS/10% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with primary antibodies against phosphorylated AKT (Ser 473) and ATK (Cell Signaling), Phopshorylated ERK 1/2 (E-4), ERK2 (C-14), TOMM20 (F-10) and β-actin (C2), all purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Proteins were detected by horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies and revealed using the SuperSignal west pico chemiluminescent substrate (Fisher Scientific).

Click-iT EdU proliferation assay

48h after seeding MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR were subjected to proliferation assay using Click-iT Plus EdU Pacific Blue Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Life Technologies), customized for flow cytometry. Briefly, cells were treated with 10 µM EdU for 2 hours and then fixed and permeabilized. EdU was detected after permeabilization by staining cells with Click-iT Plus reaction cocktail containing the Fluorescent dye picolylazide for 30 min at RT. Samples were then washed and analyzed using flow cytometer (Fortessa, BD Bioscence). Background values were estimated by measuring non-EdU labeled, but Click-iT stained cells. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Migration assay

MCF7 and MCF7 DoxyR cells were allowed to grow in regular growth medium until they were 70-80 % confluent. Next, to create a scratch of the cell monolayer, a p200 pipette tip was used. Cells were washed twice with PBS and then incubated at 37° C in regular medium for 24h. The migration assay was evaluated using Incucyte Zoom (Essen Bioscience) [55]. The rate of migration was measured by quantifying the % of wound closure area, determined using the software ImageJ, according to the formula:

% of wound closure = [(At = 0 h - At = Δ h)/At = 0 h] × 100%

Statistical analysis

Data is represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), taken over ≥ 3 independent experiments, with ≥ 3 technical replicates per experiment, unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was measured using the t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Author contributions

Professor Michael Lisanti and Dr. Federica Sotgia conceived and initiated this collaborative project. All the experiments in this paper were performed by Dr. Ernestina M. De Francesco, with minor technical assistance from other lab members; Dr. Ernestina M. De Francesco analyzed all the data and generated the final figures and tables, and she wrote significant portions of the manuscript. Drs. Michael P. Lisanti, Ernestina M. De Francesco, Gloria Bonuccelli, Marcello Maggiolini and Federica Sotgia all contributed to the writing and the editing of the manuscript. Professor Lisanti generated the schematic summary diagrams.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the University of Manchester, which allocated start-up funds and administered a donation, to provide the necessary resources required to start and complete this drug discovery project (to MPL and FS). Dr. Ernestina M. De Francesco was supported by a fellowship from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) co-funded by the European Union. The Lisanti and Sotgia Laboratories are currently supported by private donations, and by funds from the Healthy Life Foundation (HLF) and the University of Salford (to MPL and FS). We also wish to thank Dr. Duncan Smith, who performed the proteomics analysis on whole cell lysates, within the CRUK Core Facility. MM was supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, IG 16719).

Conflicts of Interest

MPL and FS hold a minority interest in Lunella, Inc.

References

1. Duggal R, Minev B, Geissinger U, Wang H, Chen NG, Koka PS, Szalay AA. Biotherapeutic approaches to target cancer stem cells. J Stem Cells. 2013; 8:135–49.

2. Scopelliti A, Cammareri P, Catalano V, Saladino V, Todaro M, Stassi G. Therapeutic implications of Cancer Initiating Cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009; 9:1005–16.

3. Berridge MV, Dong L, Neuzil J. Mitochondrial DNA in Tumor Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis: Role of Horizontal mtDNA Transfer. Cancer Res. 2015; 75:3203–08.

4. Brooks MD, Burness ML, Wicha MS. Therapeutic Implications of Cellular Heterogeneity and Plasticity in Breast Cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2015; 17:260–71.

5. Tan AS, Baty JW, Dong LF, Bezawork-Geleta A, Endaya B, Goodwin J, Bajzikova M, Kovarova J, Peterka M, Yan B, Pesdar EA, Sobol M, Filimonenko A, et al. Mitochondrial genome acquisition restores respiratory function and tumorigenic potential of cancer cells without mitochondrial DNA. Cell Metab. 2015; 21:81–94.

6. Chandler JM, Lagasse E. Cancerous stem cells: deviant stem cells with cancer-causing misbehavior. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010; 1:13.

7. Zhang M, Rosen JM. Stem cells in the etiology and treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006; 16:60–64.

8. Lamb R, Harrison H, Hulit J, Smith DL, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondria as new therapeutic targets for eradicating cancer stem cells: quantitative proteomics and functional validation via MCT1/2 inhibition. Oncotarget. 2014; 5:11029–37. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2789

9. Peiris-Pagès M, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer stem cell metabolism. Breast Cancer Res. 2016; 18:55.

10. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagés M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017; 14:11–31.

11. Farnie G, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. High mitochondrial mass identifies a sub-population of stem-like cancer cells that are chemo-resistant. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:30472–86. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5401

12. Lamb R, Bonuccelli G, Ozsvári B, Peiris-Pagès M, Fiorillo M, Smith DL, Bevilacqua G, Mazzanti CM, McDonnell LA, Naccarato AG, Chiu M, Wynne L, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, et al. Mitochondrial mass, a new metabolic biomarker for stem-like cancer cells: understanding WNT/FGF-driven anabolic signaling. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:30453–71. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5852

13. Bonuccelli G, De Francesco EM, de Boer R, Tanowitz HB, Lisanti MP. NADH autofluorescence, a new metabolic biomarker for cancer stem cells: identification of Vitamin C and CAPE as natural products targeting “stemness”. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:20667–78. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15400

14. Lamb R, Ozsvari B, Lisanti CL, Tanowitz HB, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Antibiotics that target mitochondria effectively eradicate cancer stem cells, across multiple tumor types: treating cancer like an infectious disease. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:4569–84. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3174

15. De Luca A, Fiorillo M, Peiris-Pagès M, Ozsvari B, Smith DL, Sanchez-Alvarez R, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Cappello AR, Pezzi V, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondrial biogenesis is required for the anchorage-independent survival and propagation of stem-like cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:14777–95. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4401

16. Bonuccelli G, Peiris-Pages M, Ozsvari B, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Targeting cancer stem cell propagation with palbociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor: telomerase drives tumor cell heterogeneity. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:9868–84. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14196

17. Fiorillo M, Lamb R, Tanowitz HB, Mutti L, Krstic-Demonacos M, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Repurposing atovaquone: targeting mitochondrial complex III and OXPHOS to eradicate cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016; 7:34084–99. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9122

18. Fiorillo M, Lamb R, Tanowitz HB, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Bedaquiline, an FDA-approved antibiotic, inhibits mitochondrial function and potently blocks the proliferative expansion of stem-like cancer cells (CSCs). Aging (Albany NY). 2016; 8:1593–607. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100983

19. Fiorillo M, Sotgia F, Sisci D, Cappello AR, Lisanti MP. Mitochondrial “power” drives tamoxifen resistance: NQO1 and GCLC are new therapeutic targets in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:20309–27. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.15852

20. Lamb R, Fiorillo M, Chadwick A, Ozsvari B, Reeves KJ, Smith DL, Clarke RB, Howell SJ, Cappello AR, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pagès M, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Doxycycline down-regulates DNA-PK and radiosensitizes tumor initiating cells: implications for more effective radiation therapy. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:14005–25. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.4159

21. Killock D. Drug therapy: can the mitochondrial adverse effects of antibiotics be exploited to target cancer metabolism? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12:190.

22. Yun J, Mullarky E, Lu C, Bosch KN, Kavalier A, Rivera K, Roper J, Chio II, Giannopoulou EG, Rago C, Muley A, Asara JM, Paik J, et al. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science. 2015; 350:1391–96.

23. Dando I, Dalla Pozza E, Biondani G, Cordani M, Palmieri M, Donadelli M. The metabolic landscape of cancer stem cells. IUBMB Life. 2015; 67:687–93.

24. Takemura Y, Satoh M, Satoh K, Hamada H, Sekido Y, Kubota S. High dose of ascorbic acid induces cell death in mesothelioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010; 394:249–53.

25. Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, Li F, Xiang Y, Raman V, Bhujwalla ZM, Felsher DW, Cheng L, Pevsner J, Lee LA, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2007; 12:230–38.

26. Schmalhausen EV, Pleten’ AP, Muronetz VI. Ascorbate-induced oxidation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003; 308:492–96.

27. Pullar JM, Carr AC, Vissers MCM. The roles of vitamin C in skin health. Nutrients. 2017; 9:E866.

28. Nechuta S, Lu W, Chen Z, Zheng Y, Gu K, Cai H, Zheng W, Shu XO. Vitamin supplement use during breast cancer treatment and survival: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011; 20:262–71.

29. Harris HR, Orsini N, Wolk A. Vitamin C and survival among women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2014; 50:1223–31.

30. Duconge J, Miranda-Massari JR, Gonzalez MJ, Jackson JA, Warnock W, Riordan NH. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin C: insights into the oral and intravenous administration of ascorbate. P R Health Sci J. 2008; 27:7–19.

31. Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, Wesley RA, Levine M. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 140:533–37.

32. Leung PY, Miyashita K, Young M, Tsao CS. Cytotoxic effect of ascorbate and its derivatives on cultured malignant and nonmalignant cell lines. Anticancer Res. 1993; 13:475–80.

33. Riordan NH, Riordan HD, Meng X, Li Y, Jackson JA. Intravenous ascorbate as a tumor cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent. Med Hypotheses. 1995; 44:207–13.

34. Uetaki M, Tabata S, Nakasuka F, Soga T, Tomita M. Metabolomic alterations in human cancer cells by vitamin C-induced oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2015; 5:13896.

35. Hoffer LJ, Robitaille L, Zakarian R, Melnychuk D, Kavan P, Agulnik J, Cohen V, Small D, Miller WH Jr. High-dose intravenous vitamin C combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: a phase I-II clinical trial. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0120228.

36. Menendez JA, Alarcón T. Metabostemness: a new cancer hallmark. Front Oncol. 2014; 4:262.

37. Khajehei M, Keshavarz T, Tabatabaee HR. Randomised double-blind trial of the effect of vitamin C on dyspareunia and vaginal discharge in women receiving doxycycline and triple sulfa for chlamydial cervicitis. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009; 49:525–30.

38. Goc A, Niedzwiecki A, Rath M. Cooperation of Doxycycline with Phytochemicals and Micronutrients Against Active and Persistent Forms of Borrelia sp. Int J Biol Sci. 2016; 12:1093–103.

39. Cursino IL, Chartone-Souza E, Nascimento AM. Synergic interaction between ascorbic acid and antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2005; 48:379–84.

40. Bonuccelli G, Tsirigos A, Whitaker-Menezes D, Pavlides S, Pestell RG, Chiavarina B, Frank PG, Flomenberg N, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Ketones and lactate “fuel” tumor growth and metastasis: evidence that epithelial cancer cells use oxidative mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2010; 9:3506–14.

41. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pestell RG, Howell A, Tykocinski ML, Nagajyothi F, Machado FS, Tanowitz HB, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Energy transfer in “parasitic” cancer metabolism: mitochondria are the powerhouse and Achilles’ heel of tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2011; 10:4208–16.

42. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Goldberg A, Lin Z, Ko YH, Flomenberg N, Wang C, Pavlides S, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Anti-estrogen resistance in breast cancer is induced by the tumor microenvironment and can be overcome by inhibiting mitochondrial function in epithelial cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011; 12:924–38.

43. Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Flomenberg N, Birbe RC, Witkiewicz AK, Howell A, Pavlides S, Tsirigos A, Ertel A, Pestell RG, Broda P, Minetti C, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Hyperactivation of oxidative mitochondrial metabolism in epithelial cancer cells in situ: visualizing the therapeutic effects of metformin in tumor tissue. Cell Cycle. 2011; 10:4047–64.

44. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Power surge: supporting cells “fuel” cancer cell mitochondria. Cell Metab. 2012; 15:4–5.

45. Ertel A, Tsirigos A, Whitaker-Menezes D, Birbe RC, Pavlides S, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Is cancer a metabolic rebellion against host aging? In the quest for immortality, tumor cells try to save themselves by boosting mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:253–63.

46. Ko YH, Lin Z, Flomenberg N, Pestell RG, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP, Martinez-Outschoorn UE. Glutamine fuels a vicious cycle of autophagy in the tumor stroma and oxidative mitochondrial metabolism in epithelial cancer cells: implications for preventing chemotherapy resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011; 12:1085–97.

47. Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Flomenberg N, Birbe RC, Witkiewicz AK, Howell A, Philp NJ, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP. Mitochondrial metabolism in cancer metastasis: visualizing tumor cell mitochondria and the “reverse Warburg effect” in positive lymph node tissue. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:1445–54.

48. Salem AF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Lin Z, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Tanowitz HB, Al-Zoubi MS, Howell A, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Two-compartment tumor metabolism: autophagy in the tumor microenvironment and oxidative mitochondrial metabolism (OXPHOS) in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:2545–56.

49. Salem AF, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Mitochondrial biogenesis in epithelial cancer cells promotes breast cancer tumor growth and confers autophagy resistance. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:4174–80.

50. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Ketone bodies and two-compartment tumor metabolism: stromal ketone production fuels mitochondrial biogenesis in epithelial cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:3956–63.

51. Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Howell A, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Ketone body utilization drives tumor growth and metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:3964–71.

52. Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Salem AF, Tsirigos A, Lamb R, Sneddon S, Hulit J, Howell A, Lisanti MP. Mitochondria “fuel” breast cancer metabolism: fifteen markers of mitochondrial biogenesis label epithelial cancer cells, but are excluded from adjacent stromal cells. Cell Cycle. 2012; 11:4390–401.

53. Sanchez-Alvarez R, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lamb R, Hulit J, Howell A, Gandara R, Sartini M, Rubin E, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in breast cancer cells prevents tumor growth: understanding chemoprevention with metformin. Cell Cycle. 2013; 12:172–82.

54. Shaw FL, Harrison H, Spence K, Ablett MP, Simões BM, Farnie G, Clarke RB. A detailed mammosphere assay protocol for the quantification of breast stem cell activity. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2012; 17:111–17.

55. Yue PY, Leung EP, Mak NK, Wong RN. A simplified method for quantifying cell migration/wound healing in 96-well plates. J Biomol Screen. 2010; 15:427–33.

All site content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

All site content, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. PII: 18428

Gerelateerde artikelen

- Lees hier hoe de Vereniging tegen Kwakzalverij, VtdK, de weg helemaal is kwijtgeraakt afgelopen jaren. Een overzicht van artikelen en publicaties

- Academische uitgevers aangeklaagd wegens uitbuiting van wetenschappers. Uitgevers verdienden in 2023 miljarden aan publicaties die uitgevoerd zijn met belastinggeld

- Yvan Wolffers overlijdt aan de gevolgen van prostaatkanker op 7 oktober 2022

- VITALITY OF LIFE BY PERSONALIZED MEDICINE Bruggen bouwen in het complementaire veld. 2 daags jubileumcongres om het 40-jarig bestaan van de NatuurApotheek en het 20+2 jarig bestaan van de Hahnemann Apotheek op 2 en 3 september 2022

- Ministerie van Economische Zaken en Klimaat (EZK) liet advies minder vlees te eten bewust weg uit klimaatcampagne, zo ontdekte Stichting Wakker Dier

- Nieuwe kankermedicijnen worden in Europa (EMA) veel later goedgekeurd dan in Amerika (FDA) en kost tienduizenden levensjaren.

- Wetenschappers van het Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek ziekenhuis zeggen met combinatiebehandeling (one-two-punch ) van reeds bestaande medicijnen de sleutel tot genezende behandeling van kanker te hebben gevonden

- Nieuw NANO-Vaccin, 2 natuurlijke peptiden , aminozuren verpakt in nanodeeltjes voorkomt melanomen en uitzaaiingen bij melanomen en blijkt als immuuntherapie uitstekend te werken

- Whole genome sequencing: toekomst van de kankerdiagnostiek? AvL start studie samen met UMC Utrecht

- Surviving terminal cancer: kunnen overlevenden van een hersentumor helpen kanker te overwinnen? Drie mannen overwonnen hun hersentumor - GBM - en 2 ervan zijn al 15 en 20 jaar vrij van kanker met eigen cocktail van bewezen niet-toxische middelen.

- AMC start studieproject EIGEN ONDERZOEK waarbij 500 patienten met darmklachten en chronische vermoeidheid zelf hun ervaringen met probiotica en beweging enz. bijhouden via een app.

- Chemo stimuleert juist kankergroei en uitzaaiïngen door verhoogde productie van het eiwit WNT16B dat ook grote rol speelt bij wondheeling

- Kanker opsporen binnen 20 minuten en een kant en klaar behandelingsvoorstel wordt binnen drie jaar mogelijk met nieuw apparaat gebaseerd op nanotechnologie.

- Effecten van medicijnen en behandelingen bij 52 aandoeningen waaronder kanker moeten volgens het Zorginstituut vermeld worden in persoonlijke medische dossiers

- vorinostat heft resistentie van kankercellen op bij melanomen en lijkt oplossing voor dure medicijnen aldus Rene Bernards van het NKI. Vorinostat blijkt ook bij recidief van zwaar voorbehandelde multiple myeloma met 94 procent bijzonder effectief

- Keer diabetes om wint zinnige zorg award voor voedingsprogramma voor diabetici

- E-sigaret blijkt 95 procent minder schadelijk dan tabak roken en stimuleert rokers te stoppen. Echter tieners lijken er juist door gestimuleerd te worden te beginnen met roken

- Zorginstituut ziet verdere verbetering van behandelingen van niercelkanker met nieuwe medicijnen en doet aanbevelingen in een rapport aan Minister Bruins.

- Bepaalde darmbacteriën kunnen de effectiviteit van immunotherapie met anti-PD medicijnen verhogen bij de behandeling van melanomen

- Mammografie zorgt nauwelijks voor vermindering van risico op overlijden aan gevorderde borstkanker maar wel voor veel meer onnodige behandelingen door overdiagnose

- Vitamine C in combinatie met Doxycycline een antibiotica doden samen kankerstamcellen en lijkt nieuwe behandelingsoptie nagenoeg zonder bijwerkingen

- Antibiotica verminderen effectiviteit van immuuntherapie terwijl aanvullende microbiota de resultaten sterk verbeteren van immuuntherapie met anti-PD medicijnen

- Goedkeuring van nieuwe kankermedicijnen meestal gebaseerd op te weinig bewijs en geven in de praktijk slechts bij de helft kleine verbeteringen in mediane overleving.

- Biliscreen, een speciale app kan via een selfie van oog vroegtijdig alvleesklierkanker en aan geelzucht gerelateerde leveraandoeningen ontdekken.

- Nederlandse DRUP studie, waarbij behandelingen worden gegeven gebaseerd op DNA mutaties en receptorenexpressie geeft hoopvolle resultaten voor uitbehandelde kankerpatienten

- Immuuntherapeutische studies zoals gepresenteerd Op ASCO 2017 in Chicago 2 t/m/ 5 juni 2017

- Propranolol, een bloeddrukverlager, blijkt effectief geneesmiddel tegen angiosarcomen en is goedgekeurd als weesgeneesmedicijn voor onderzoek door Europese Commissie.

- Darmflora met gevarieerde bacterien geven betere resultaten voor immuuntherapie bij melanomen dan een minder gevarieerde darmflora.

- Zuurstof tekort bevordert groei kankercellen. Toevoeging van zuurstof - ozontherapie - kan groei van tumorcellen remmen of zelfs tegengaan

- Melkzuurbacterien - probiotica aanwezig in gezond borstweefsel beschermt vrouwen tegen borstkanker blijkt uit kleinschalige studie

- The quest for the cures of cancer, bekijk documentaire van oncologen, wetenschappers en patienten over natuurlijke geneeswijzen bij kanker

- Vader Pieter en zoon Bernard van Vollenhoven genezen van uitgezaaide melanoom en lymfklierkanker. Ook Jimmy Carter blijkt kankervrij. Bepalen geld en macht de kansen op genezen van kanker?

- Gepersonaliseerd vaccin voor immuuntherapie is de sleutel tot voorkomen en genezen van kanker ontdekt een team van wetenschappers.

- LUMC opent Nederlandse Donor Feces Bank (NDFB) - poepbank waar iedereen die gezond is zijn ontlasting kan doneren, welke gebruikt wordt voor herstel van darmflora bij zieke patienten.via neussonde

- In Nederland overlijden elk jaar de meeste mensen onder de 65 jaar aan kanker en Nederland staat tweede voor mensen ouder dan 65 jaar van heel Europa

- Dr. Nicolas Gonzalez sterft onder verdachte omstandigheden. Dr. Gonzalez is in 1 jaar de tijd de 10e complementair werkende arts die overlijdt door moord of onder verdachte omstandigheden

- Nieuwe aanpak van kanker gevonden door Amerikaanse tiener?

- PLEKHA7 een eiwit speelt cruciale rol in apoptose - zefldoding van kankercellen. Onderzoekers aan de Mayo Clinic ontdekken dat reparatie van PLEKHA7 vorming van tumoren kan voorkomen.

- Doorbraak in bestrijden van chronische pijn met de lichaamseigene ontstekingsremmende stof palmitoylethanolamide welke geen bijwerkiingen geeft

- Darmkankeronderzoek: de eerste resultaten gepresenteerd. Bij 1 op de 28 werd iets afwijkends gevonden

- ZONmw pleit in rapport voor meer integratie van alternatieve, complementaire, aanvullende middelen en behandelingen in de reguliere gezondheidszorg

- Nano-MRI met nanovloeistof ontdekt sneller uitzaaiingen in lymfklieren en kan behandeling van kanker sneller doen starten of juist aantonen dat behandelingen niet nodig zijn.

- Welke behandeling krijgt de patiente met dikke darmkanker uit de Wereld Draait Door van vanavond 8 oktober 2013?

- Nieuwe Tieten van Sacha Polak. is een persoonlijke en openhartige documentaire over wel of niet preventief haar borsten te laten verwijderen omdat.ze draagster is van het BRCA-1 gen

- Mamma waarom moet je naar het ziekenhuis? Nieuwe animaties en tekeningen voor peuters en kinderen die een ouder met kanker hebben op website van stichting Kankerspoken.

- Erasmus Medisch Centrum gaat onderzoek doen naar effecten van hyperthermie bij kanker als aanvulling op chemo of bestraling

- Injecties met 3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA) in tumorweefsel zou effectiever werken dan operatie en chemo bij borstkanker..Deze antiglycolitic therapie beinvloed metabolisch proces in kankercel en leidt tot natuurlijke celdood

- Time released chemo toedienen via nanodeeltjes bij hersentumoren - glioma blastoma multiforme, verdubbelt overlevingstijd in dierstudies

- Op menselijke genen kan geen patent worden verkregen zo luidt het oordeel van het Hooggerechtshof in de Verenigde Staten. Op synthetische DNA-sequenties mag dit echter wel.

- In Nederland bestaat er grote ongelijkheid in gebruik van dure diagnostiek en behandelingen voor kankerpatienten, aldus prof. dr. Carin Uyl-de Groot.

- Botuitzaaiingen worden vaak veroorzaakt door stamcellen in het beenmerg, ontdekken wetenschappers.

- Nieuwe vorm van uitstrijkje zou vroegtijdig eierstokkanker, baarmoederkanker en baarmoederhalskanker ontdekken, beweren Amerikaanse onderzoekers

- BG-12 - dimethyl fumaraat - verbetert significant kwaliteit van leven en vermindert klachten van bepaalde vorm van MS - multiple sclerose (RR MS = de schubvorm van MS), aldus meta analyse van fase III studies.

- Darmkanker stijgt met 42 procent de laatste tien jaar. Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds start groot internationaal onderzoek naar effecten van leefstijl en voeding op risico van darmkanker

- Voedingstoffen als medicijn: biochemische kaart van menselijk lichaam voltooid. Ziektes kunnen voorkomen worden door individueel voedingspatroon.

- Bloedtest kan bepalen of er chemo nodig is bij uitgezaaide borstkanker en darmkanker, aldus promotie onderzoek van Bianca Mostert

Plaats een reactie ...

4 Reacties op "Vitamine C in combinatie met Doxycycline een antibiotica doden samen kankerstamcellen en lijkt nieuwe behandelingsoptie nagenoeg zonder bijwerkingen"